(Press-News.org) A new study pins down a major factor behind the appearance of superconductivity—the ability to conduct electricity with 100 percent efficiency—in a promising copper-oxide material.

Scientists used carefully timed pairs of laser pulses at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to trigger superconductivity in the material and immediately take x-ray snapshots of its atomic and electronic structure as superconductivity emerged.

They discovered that so-called "charge stripes" of increased electrical charge melted away as superconductivity appeared. Further, the results help rule out the theory that shifts in the material's atomic lattice hinder the onset of superconductivity.

Armed with this new understanding, scientists may be able to develop new techniques to eliminate charge stripes and help pave the way for room-temperature superconductivity, often considered the holy grail of condensed matter physics. The demonstrated ability to rapidly switch between the insulating and superconducting states could also prove useful in advanced electronics and computation.

The results, from a collaboration led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter in Germany and the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC and Brookhaven national laboratories, were published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"The very short timescales and the need for high spatial resolution made this experiment extraordinarily challenging," said co-author Michael Först, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute. "Now, using femtosecond x-ray pulses, we found a way to capture the quadrillionths-of-a-second dynamics of the charges and the crystal lattice. We've broken new ground in understanding light-induced superconductivity."

Ripples in Quantum Sand

The compound used in this study was a layered material consisting of lanthanum, barium, copper, and oxygen grown at Brookhaven Lab by physicist Genda Gu. Each copper oxide layer contained the crucial charge stripes.

"Imagine these stripes as ripples frozen in the sand," said John Hill, a Brookhaven Lab physicist and coauthor on the study. "Each layer has all the ripples going in one direction, but in the neighboring layers they run crosswise. From above, this looks like strings in a pile of tennis racquets. We believe that this pattern prevents each layer from talking to the next, thus frustrating superconductivity."

To excite the material and push it into the superconducting phase, the scientists used mid-infrared laser pulses to "melt" those frozen ripples. These pulses had previously been shown to induce superconductivity in a related compound at a frigid 10 Kelvin (minus 442 degrees Fahrenheit).

"The charge stripes disappeared immediately," Hill said. "But specific distortions in the crystal lattice, which had been thought to stabilize these stripes, lingered much longer. This shows that only the charge stripes inhibit superconductivity."

Stroboscopic Snapshots

To capture these stripes in action, the collaboration turned to SLAC's LCLS x-ray laser, which works like a camera with a shutter speed faster than 100 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second, and provides atomic-scale image resolution. LCLS uses a section of SLAC's 2-mile-long linear accelerator to generate the electrons that give off x-ray light.

"This represents a very important result in the field of superconductivity using LCLS," said Josh Turner, an LCLS staff scientist. "It demonstrates how we can unravel different types of complex mechanisms in superconductivity that have, up until now, been inseparable."

He added, "To make this measurement, we had to push the limits of our current capabilities. We had to measure a very weak, barely detectable signal with state-of-the-art detectors, and we had to tune the number of x-rays in each laser pulse to see the signal from the stripes without destroying the sample."

The researchers used the so-called "pump-probe" approach: an optical laser pulse strikes and excites the lattice (pump) and an ultrabright x-ray laser pulse is carefully synchronized to follow within femtoseconds and measure the lattice and stripe configurations (probe). Each round of tests results in some 20,000 x-ray snapshots of the changing lattice and charge stripes, a bit like a strobe light rapidly illuminating the process.

To measure the changes with high spatial resolution, the team used a technique called resonant soft x-ray diffraction. The LCLS x-rays strike and scatter off the crystal into the detector, carrying time-stamped signatures of the material's charge and lattice structure that the physicists then used to reconstruct the rise and fall of superconducting conditions.

"By carefully choosing a very particular x-ray energy, we are able to emphasize the scattering from the charge stripes," said Brookhaven Lab physicist Stuart Wilkins, another co-author on the study. "This allows us to single out a very weak signal from the background."

Toward Superior Superconductors

The x-ray scattering measurements revealed that the lattice distortion persists for more than 10 picoseconds (trillionths of a second)—long after the charge stripes melted and superconductivity appeared, which happened in less than 400 femtoseconds. Slight as it may sound, those extra trillionths of a second make a huge difference.

"The findings suggest that the relatively weak and long-lasting lattice shifts do not play an essential role in the presence of superconductivity," Hill said. "We can now narrow our focus on the stripes to further pin down the underlying mechanism and potentially engineer superior materials."

Andrea Cavalleri, Director of the Max Planck Institute, said, "Light-induced superconductivity was only recently discovered, and we're already seeing fascinating implications for understanding it and going to higher temperatures. In fact, we have observed the signature of light-induced superconductivity in materials all the way up to 300 Kelvin (80 degrees Fahrenheit)—that's really a significant breakthrough that warrants much deeper investigations."

INFORMATION:

Other collaborators on this research include the University of Groningen, the University of Oxford, Diamond Light Source, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Stanford University, the European XFEL, the University of Hamburg and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science.

The research conducted at the Soft X-ray Materials Science (SXR) experimental station at SLAC's LCLS—a DOE Office of Science user facility—was funded by Stanford University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the University of Hamburg, and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL). Work performed at Brookhaven Lab was supported by the DOE's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit applied science and technology organization.

Scientists capture ultrafast snapshots of light-driven superconductivity

X-rays reveal how rapidly vanishing 'charge stripes' may be behind laser-induced high-temperature superconductivity

2014-04-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Eavesdropping on brain cell chatter

2014-04-16

Everything we do — all of our movements, thoughts and feelings – are the result of neurons talking with one another, and recent studies have suggested that some of the conversations might not be all that private. Brain cells known as astrocytes may be listening in on, or even participating in, some of those discussions. But a new mouse study suggests that astrocytes might only be tuning in part of the time — specifically, when the neurons get really excited about something. This research, published in Neuron, was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders ...

How kids' brain structures grow as memory develops

2014-04-16

Our ability to store memories improves during childhood, associated with structural changes in the hippocampus and its connections with prefrontal and parietal cortices. New research from UC Davis is exploring how these brain regions develop at this crucial time. Eventually, that could give insights into disorders that typically emerge in the transition into and during adolescence and affect memory, such as schizophrenia and depression.

Located deep in the middle of the brain, the hippocampus plays a key role in forming memories. It looks something like two curving fingers ...

Theoretical biophysics: Adventurous bacteria

2014-04-16

To reproduce or to conquer the world? Surprisingly, bacteria also face this problem. Theoretical biophysicists at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich have now shown how these organisms should decide how best to preserve their species.

The bacterium Bacillus subtilis is quite adaptable. It moves about in liquids and on agar surfaces by means of flagella. Alternatively, it can stick to an underlying substrate. Actually, the bacteria proliferate most effectively in this stationary state, while motile bacteria reproduce at a notably lower rate.

In order to sustain ...

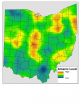

Significant baseline levels of arsenic found in Ohio soils are due to natural processes

2014-04-16

RICHLAND, Wash. – Geologic and soil processes are to blame for significant baseline levels of arsenic in soil throughout Ohio, according to a study published recently in the Journal of Environmental Quality.

The analysis of 842 soil samples from all corners of Ohio showed that every single sample had concentrations higher than the screening level of concern recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The findings should not alarm the public, say the authors, who note that regulatory levels typically are set far below those thought to be harmful. Rather, the ...

Preterm births, multiples, and fertility treatment

2014-04-16

While it is well known that fertility treatments are the leading cause of increases in multiple gestations and that multiples are at elevated risk of premature birth, these results are not inevitable, concludes an article in Fertility and Sterility. The article identifies six changes in policy and practice that can reduce the odds of multiple births and prematurity, including expanding insurance coverage for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and improving doctor-patient communications about the risks associated with twins.

Financial pressures provide a powerful incentive for ...

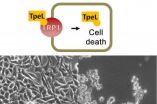

Gate for bacterial toxins found

2014-04-16

Prof. Dr. Dr. Klaus Aktories and Dr. Panagiotis Papatheodorou from the Institute of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology of the University of Freiburg have discovered the receptor responsible for smuggling the toxin of the bacterium Clostridium perfringens into the cell. The TpeL toxin, which is formed by C. perfringens, a pathogen that causes gas gangrene and food poisoning. It is very similar to the toxins of many other hospital germs of the genus Clostridium. The toxins bind to surface molecules and creep into the body cell, where they lead to cell death. ...

Scientists explain how memories stick together

2014-04-16

LA JOLLA—Scientists at the Salk Institute have created a new model of memory that explains how neurons retain select memories a few hours after an event.

This new framework provides a more complete picture of how memory works, which can inform research into disorders liked Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, post-traumatic stress and learning disabilities.

"Previous models of memory were based on fast activity patterns," says Terry Sejnowski, holder of Salk's Francis Crick Chair and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. "Our new model of memory makes it possible to ...

Shade grown coffee shrinking as a proportion of global coffee production

2014-04-16

The proportion of land used to cultivate shade grown coffee, relative to the total land area of coffee cultivation, has fallen by nearly 20 percent globally since 1996, according to a new study by scientists from The University of Texas at Austin and five other institutions.

The study's authors say the global shift toward a more intensive style of coffee farming is probably having a negative effect on the environment, communities and individual farmers.

"The paradox is that there is greater public interest than ever in environmentally friendly coffee, but where coffee ...

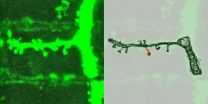

Synapses -- stability in transformation

2014-04-16

This news release is available in German. Synapses are the points of contact at which information is transmitted between neurons. Without them, we would not be able to form thoughts or remember things. For memories to endure, synapses sometimes have to remain stable for very long periods. But how can a synapse last if its components have to be replaced regularly? Scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried near Munich have taken a decisive step towards answering this question. They have succeeded in demonstrating that when a synapse is formed, ...

Scratching the surface: Microbial etchings in impact glass and the search for life on Mars

2014-04-16

Boulder, Colo., USA – Haley M. Sapers and colleagues provide what may be the first report of biological activity preserved in impact glass. Recent research has suggested that impact events create novel within-rock microbial habitats. In their paper, "Enigmatic tubular features in impact glass," Sapers and colleagues analyze tubular features in hydrothermally altered impact glass from the Ries Impact Structure, Germany, that are remarkably similar to the bioalteration textures observed in volcanic glasses.

The authors note that mineral-forming processes cannot easily ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cosmic rays streamed through Earth’s atmosphere 41,000 years ago

ACP issues clinical recommendations for newer diabetes treatments

New insights into the connections between alcohol consumption and aggressive liver cancer

Unraveling water mysteries beyond Earth

Signs of multiple sclerosis show up in blood years before symptoms

Ghost particle on the scales

Light show in living cells

Climate change will increase value of residential rooftop solar panels across US, study shows

Could the liver hold the key to better cancer treatments?

Warming of Antarctic deep-sea waters contribute to sea level rise in North Atlantic, study finds

Study opens new avenue for immunotherapy drug development

Baby sharks prefer being closer to shore, show scientists

UBC research helps migrating salmon survive mortality hot-spot

Technical Trials for Easing the (Cosmological) Tension

Mapping plant functional diversity from space: HKU ecologists revolutionize ecosystem monitoring with novel field-satellite integration

Lightweight and flexible yet strong? Versatile fibers with dramatically improved energy storage capacity

3 ways to improve diabetes care through telehealth

A flexible and efficient DC power converter for sustainable-energy microgrids

Key protein regulates immune response to viruses in mammal cells

Development of organic semiconductors featuring ultrafast electrons

Cancer is a disease of aging, but studies of older adults sorely lacking

Dietary treatment more effective than medicines in IBS

Silent flight edges closer to take off, according to new research

Why can zebrafish regenerate damaged heart tissue, while other fish species cannot?

Keck School of Medicine of USC orthopaedic surgery chair elected as 2024 AAAS fellow

Returning rare earth element production to the United States

University of Houston Professor Kaushik Rajashekara elected International Fellow of the Engineering Academy of Japan

Solving antibiotic and pesticide resistance with infectious worms

Three ORNL scientists elected AAAS Fellows

Rice bioengineers win $1.4 million ARPA-H grant for osteoarthritis research

[Press-News.org] Scientists capture ultrafast snapshots of light-driven superconductivityX-rays reveal how rapidly vanishing 'charge stripes' may be behind laser-induced high-temperature superconductivity