(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL, September 2, 2014 – In a new study that could ultimately lead to many new medicines, scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have adapted a chemical approach to turn diseased cells into unique manufacturing sites for molecules that can treat a form of muscular dystrophy.

"We're using a cell as a reaction vessel and a disease-causing defect as a catalyst to synthesize a treatment in a diseased cell," said TSRI Professor Matthew Disney.

"Because the treatment is synthesized only in diseased cells, the compounds could provide highly specific therapeutics that only act when a disease is present. This means we can potentially treat a host of conditions in a very selective and precise manner in totally unprecedented ways."

The promising research was published recently in the international chemistry journal Angewandte Chemie.

Targeting RNA Repeats

In general, small, low molecular weight compounds can pass the blood-brain barrier, while larger, higher weight compounds tend to be more potent. In the new study, however, small molecules became powerful inhibitors when they bound to targets in cells expressing an RNA defect, such as those found in myotonic dystrophy.

Myotonic dystrophy type 2, a relatively mild and uncommon form of the progressive muscle weakening disease, is caused by a type of RNA defect known as a "tetranucleotide repeat," in which a series of four nucleotides is repeated more times than normal in an individual's genetic code. In this case, a cytosine-cytosine-uracil-guanine (CCUG) repeat binds to the protein MBNL1, rendering it inactive and resulting in RNA splicing abnormalities that, in turn, results in the disease.

In the study, a pair of small molecule "modules" the scientists developed binds to adjacent parts of the defect in a living cell, bringing these groups close together. Under these conditions, the adjacent parts reach out to one another and, as Disney describes it, permanently hold hands. Once that connection is made, the small molecule binds tightly to the defect, potently reversing disease defects on a molecular level.

"When these compounds assemble in the cell, they are 1,000 times more potent than the small molecule itself and 100 times more potent than our most active lead compound," said Research Associate Suzanne Rzuczek, the first author of the study. "This is the first time this has been validated in live cells."

Click Chemistry Construction

The basic process used by Disney and his colleagues is known as "click chemistry"—a process invented by Nobel laureate K. Barry Sharpless, a chemist at TSRI, to quickly produce substances by attaching small units or modules together in much the same way this occurs naturally.

"In my opinion, this is one unique and a nearly ideal application of the process Sharpless and his colleagues first developed," Disney said.

Given the predictability of the process and the nearly endless combinations, translating such an approach to cellular systems could be enormously productive, Disney said. RNAs make ideal targets because they are modular, just like the compounds for which they provide a molecular template.

Not only that, he added, but many similar RNAs cause a host of incurable diseases such as ALS (Lou Gehrig's Disease), Huntington's disease and more than 20 others for which there are no known cures, making this approach a potential route to develop lead therapeutics to this large class of debilitating diseases.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Rzuczek and Disney, the other author of the study, "A Toxic RNA Catalyzes the In Cellulo Synthesis of Its Own Inhibitor," is HaJeung Park of TSRI. For more information on the study, see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201406465/abstract

The work was supported by the Muscular Dystrophy Foundation, the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation and the State of Florida.

Scripps Florida scientists make diseased cells synthesize their own drug

2014-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mirabegron for overactive bladder: Added benefit not proven

2014-09-02

Mirabegron (trade name: Betmiga) has been approved since December 2012 for the treatment of adults with overactive bladder. In an early benefit assessment pursuant to the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medicinal Products (AMNOG), the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined whether this new drug offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy specified by the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA).

Mirabegron had an advantage with regard to side effects: Dry mouth was less common in comparison with tolterodine. No added ...

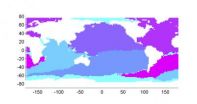

Giant garbage patches help redefine ocean boundaries

2014-09-02

WASHINGTON, D.C., September 2, 2014 – The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is an area of environmental concern between Hawaii and California where the ocean surface is marred by scattered pieces of plastic, which outweigh plankton in that part of the ocean and pose risks to fish, turtles and birds that eat the trash. Scientists believe the garbage patch is but one of at least five, each located in the center of large, circular ocean currents called gyres that suck in and trap floating debris.

Researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), in Sydney, Australia, ...

New method for non-invasive prostate cancer screening

2014-09-02

WASHINGTON D.C., Sept. 2, 2014 – Cancer screening is a critical approach for preventing cancer deaths because cases caught early are often more treatable. But while there are already existing ways to screen for different types of cancer, there is a great need for even more safe, cheap and effective methods to save even more lives.

Now a team of researchers led by Shaoxin Li at Guangdong Medical College in China has demonstrated the potential of a new, non-invasive method to screen for prostate cancer, a common type of cancer in men worldwide. They describe their laboratory ...

Scientists create renewable fossil fuel alternative using bacteria

2014-09-02

The development is a step towards commercial production of a source of fuel that could one day provide an alternative to fossil fuels.

Propane is an appealing source of cleaner fuel because it has an existing global market. It is already produced as a by-product during natural gas processing and petroleum refining, but both are finite resources. In its current form it makes up the bulk of LPG (liquid petroleum gas), which is used in many applications, from central heating to camping stoves and conventional motor vehicles.

In a new study, the team of scientists from ...

A handsome face could mean lower semen quality

2014-09-02

Contrary to what one might expect, facial masculinity was negatively associated with semen quality in a recent Journal of Evolutionary Biology study. As increased levels of testosterone have been demonstrated to impair sperm production, this finding may indicate a trade-off between investments in secondary sexual signaling (i.e. facial masculinity) and fertility.

Interestingly, males estimated facial images generally more attractive than females did, suggesting that males may generally overestimate the attractiveness of other men to females.

INFORMATION: END ...

Underwater grass comeback bodes well for Chesapeake Bay

2014-09-02

CAMBRIDGE, MD (September 2, 2014)—The Susquehanna Flats, a large bed of underwater grasses near the mouth of the Susquehanna River, virtually disappeared from the upper Chesapeake Bay after Tropical Storm Agnes more than 40 years ago. However, the grasses mysteriously began to come back in the early 2000s. Today, the bed is one of the biggest and healthiest in the Bay, spanning some 20 square miles. A new study by scientists at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science explores what's behind this major comeback.

"This is a story about resilience," said ...

Men who exercise less likely to wake up to urinate

2014-09-02

MAYWOOD, Ill – Men who are physically active are at lower risk of nocturia (waking up at night to urinate), according to a study led by a Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine researcher.

The study by Kate Wolin, ScD, and colleagues is published online ahead of print in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, the official journal of the American College of Sports Medicine.

Nocturia is the most common and bothersome lower urinary tract symptom in men. It can be due to an enlarged prostate known as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) -- as the prostate ...

Observing the onset of a magnetic substorm

2014-09-02

Magnetic substorms, the disruptions in geomagnetic activity that cause brightening of aurora, may sometimes be driven by a different process than generally thought, a new study in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics shows.

Hwang et al. report observations using the Cluster spacecraft and ground-based magnetometers associated with the onset of a substorm. They saw two consecutive sudden jumps in the current sheet normal component of the magnetic field in the plasma sheet (the surface of dense plasma that lies approximately in Earth's equatorial plane), separated ...

Researchers uncover hidden infection route of major bacterial pathogen

2014-09-02

Researchers at the University of Liverpool's Institute of Infection and Global Health have discovered the pattern of infection of the bacterium responsible for causing severe lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is usually harmless to humans, but in people with cystic fibrosis (CF) or who have weakened immune systems – such as those who have had an operation or treatment for cancer – it can cause infections that are resistant to antibiotics. In CF patients in particular, infections can be impossible to eradicate from the lungs.

The ...

Aging gracefully: Diving seabirds shed light on declines with age

2014-09-02

Scientists who studied long-lived diving birds, which represent valuable models to examine aging in the wild, found that blood oxygen stores, resting metabolism and thyroid hormone levels all declined with age, although diving performance did not. Apparently, physiological changes do occur with age in long-lived species, but they may have no detectable effect on behavioral performance.

The Functional Ecology findings suggest that reductions in metabolism with age can be viewed as strategic restraint on the part of individuals who are likely to encounter energy-related ...