(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, May 21, 2015 -- Exposure to fine particulate air pollution during pregnancy through the first two years of a child's life may be associated with an increased risk of the child developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a condition that affects one in 68 children, according to a University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health investigation of children in southwestern Pennsylvania.

The research is funded by The Heinz Endowments and published in the July edition of Environmental Research.

"Autism spectrum disorders are lifelong conditions for which there is no cure and limited treatment options, so there is an urgent need to identify any risk factors that we could mitigate, such as pollution," said lead author Evelyn Talbott, Dr.P.H., professor of epidemiology at Pitt Public Health. "Our findings reflect an association, but do not prove causality. Further investigation is needed to determine possible biological mechanisms for such an association."

Dr. Talbott and her colleagues performed a population-based, case-control study of families with and without ASD living in six southwestern Pennsylvania counties. They obtained detailed information about where the mothers lived before, during and after pregnancy and, using a model developed by Pitt Public Health assistant professor and study co-author Jane Clougherty, Sc.D., were able to estimate individual exposure to a type of air pollution called PM2.5.

This type of pollution refers to particles found in the air that are less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, or 1/30th the average width of a human hair. PM2.5 includes dust, dirt, soot and smoke. Because of its small size, PM2.5 can reach deeply into the lungs and get into the blood stream. Southwestern Pennsylvania has consistently ranked among the nation's worst regions for PM2.5 levels, according to data collected by the American Lung Association.

"There is increasing and compelling evidence that points to associations between Pittsburgh's poor air quality and health problems, especially those affecting our children and including issues such as autism spectrum disorder and asthma," said Grant Oliphant, president of The Heinz Endowments. "While we recognize that further study is needed, we must remain vigilant about the need to improve our air quality and to protect the vulnerable. Our community deserves a healthy environment and clean air."

Autism spectrum disorders are a range of conditions characterized by social deficits and communication difficulties that typically become apparent early in childhood. Reported cases of ASD have risen nearly eight-fold in the last two decades. While previous studies have shown the increase to be partially due to changes in diagnostic practices and greater public awareness of autism, this does not fully explain the increased prevalence. Both genetic and environmental factors are believed to be responsible.

Dr. Talbott and her team interviewed the families of 211 children with ASD and 219 children without ASD born between 2005 and 2009. The families lived in Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Washington and Westmoreland counties. Estimated average exposure to PM2.5 before, during and after pregnancy was compared between children with and without ASD.

Based on the child's exposure to concentrations of PM2.5 during the mother's pregnancy and the first two years of life, the Pitt Public Health team found that children who fell into higher exposure groups were at an approximate 1.5-fold greater risk of ASD after accounting for other factors associated with the child's risk for ASD -- such as the mother's age, education and smoking during pregnancy. This risk estimate is in agreement with several other recent investigations of PM2.5 and autism.

A previous Pitt Public Health analysis of the study population revealed an association between ASD and increased levels of air toxics, including chromium and styrene. Studies by other institutions using different populations also have associated pollutants with ASD.

"Air pollution levels have been declining since the 1990s; however, we know that pockets of increased levels of air pollution remain throughout our region and other areas," said Dr. Talbott. "Our study builds on previous work in other regions showing that pollution exposures may be involved in ASD. Going forward, I would like to see studies that explore the biological mechanisms that may underlie this association."

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors of this study are Vincent C. Arena, Ph.D., Judith R. Rager, M.P.H., Drew R. Michanowicz, Dr.P.H., Ravi K. Sharma, Ph.D., and Shaina L. Stacy, Ph.D., all of Pitt Public Health.

About the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health

The University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, founded in 1948 and now one of the top-ranked schools of public health in the United States, conducts research on public health and medical care that improves the lives of millions of people around the world. Pitt Public Health is a leader in devising new methods to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases, HIV/AIDS, cancer and other important public health problems. For more information about Pitt Public Health, visit the school's Web site at http://www.publichealth.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact:

Wendy Zellner

Phone: 412-586-9771

E-mail: ZellnerWL@upmc.edu

Online customer service agents who use emoticons and who are fast typists may have a better chance of putting smiles on their customers' faces during business-related text chats, according to researchers.

In a study, people who text chatted with customer service agents gave higher scores to the agents who used emoticons in their responses than agents who did not use emoticons, said S. Shyam Sundar, Distinguished Professor of Communications and co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory. The customers also reported that agents who used emoticons were more personal ...

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine have unraveled one of the mysteries of how a small group of immune cells work: That some inflammation-fighting immune cells may actually convert into cells that trigger disease.

Their findings, recently reported in the journal Pathogens, could lead to advances in fighting diseases, said the project's lead researcher Pushpa Pandiyan, an assistant professor at the dental school.

The cells at work

A type of white blood cell, called T-cells, is one of the body's critical disease fighters. Regulatory ...

Scientists from the Institut Pasteur and CNRS, in collaboration with scientists from the Institut Gustave Roussy and CEA, have succeeded in restoring normal activity in cells isolated from patients with the premature aging disease Cockayne syndrome. They have uncovered the role played in these cells by an enzyme, the HTRA3 protease.

This enzyme is overexpressed in Cockayne syndrome patient cells, and leads to mitochondrial defects, which in turn play a crucial role in the appearance of symptoms leading to aging in affected children. These findings, published in the ...

BOZEMAN, Mont. -- Montana State University researchers and their collaborators have published their findings about a chemical compound that shows potential for treating rheumatoid arthritis.

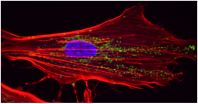

The paper ran in the June issue of the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (JPET), and one of its illustrations is featured on the cover. JPET is a leading scientific journal that covers all aspects of pharmacology, a field that investigates the effects of drugs on biological systems and vice versa.

"This journal is one of the top journals that reports new types ...

According to small and medium-sized enterprises, sizable social security and other wage-related costs still form the single greatest obstacle for improving productivity. Additionally, a lack of competence among supervisors was also seen as an obstacle for productivity. This information is from a newly published survey by the Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT), which is a follow-up to a study on the obstacles that restrain the productivity of companies published in 1997. A total of 239 representatives from Finnish small and medium-sized enterprises responded to ...

PHOENIX -- Prior studies have shown that most dog bite injuries result from family dogs. A new study conducted by Mayo Clinic and Phoenix Children's Hospital shed some further light on the nature of these injuries.

The American Veterinary association has designated this week as Dog Bite Prevention Week.

The study, published last month in the Journal of Pediatric Surgery, demonstrated that more than 50 percent of the dog bites injuries treated at Phoenix Children's Hospital came from dogs belonging to an immediate family member.

The retrospective study looked at a ...

The advice, whether from Shakespeare or a modern self-help guru, is common: Be true to yourself. New research suggests that this drive for authenticity -- living in accordance with our sense of self, emotions, and values -- may be so fundamental that we actually feel immoral and impure when we violate our true sense of self. This sense of impurity, in turn, may lead us to engage in cleansing or charitable behaviors as a way of clearing our conscience.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our work ...

Two words that arouse immediate fear in some people inspire something else altogether in Jennifer Fill.

"I love snakes and fire," Fill says. "When I was looking at grad schools, I thought, 'if I can just combine those two things, I bet I'll be really happy.'"

It's not about cozy campfires or garden-variety garters for Fill, a biologist who recently defended her dissertation at the University of South Carolina. The fires she's interested in are forest fires, and the snake that was the subject of her doctoral studies is Crotalus adamanteus, commonly called the eastern diamondback ...

A new report on New York City's Expanded Success Initiative (ESI), which is designed to boost college and career readiness among Black and Latino male students, finds that the schools involved are changing the way they operate and offering students opportunities they would not otherwise have.

"There is strong evidence that these schools are doing something different as a result of ESI," says the study's lead author, Adriana Villavicencio, senior research associate at the Research Alliance for New York City Schools. "We are seeing important shifts in the tone and culture ...

Bacteria that live in the guts of cicadas have split into many separate but interdependent species in a strange evolutionary phenomenon that leaves them reliant on a bloated genome, a new paper by CIFAR Fellow John McCutcheon's lab (University of Montana) has found.

Cicadas subsist on tree sap, which doesn't provide them all the nutrients they need to live. Bacteria in their gut, including one called Hodgkinia, turns the sap into amino acids that sustain them during their unusual lives. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground before emerging in droves, singing loudly, ...