(Press-News.org) Cold Spring Harbor, NY -- A team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has identified a set of genes that control stem cell production in tomato. Mutations in these genes explain the origin of mammoth beefsteak tomatoes. More important, the research suggests how breeders can fine-tune fruit size in potentially any fruit-bearing crop. The research appears online today in Nature Genetics.

In its original, wild form the tomato plant produces tiny, berry-sized fruits. Yet among the first tomatoes brought to Europe from Mexico by conquistador Hernan Cortez in the early 16th century were the huge beefsteaks. Producing fruits that often weigh in at over a pound, this variety has long been understood to be a freak of nature, but only now do we know how it came to be.

The secret of the beefsteak tomato, CSHL Associate Professor Zachary Lippman and colleagues show, has to do with the number of stem cells in the plant's growing tip, called the meristem. Specifically, the team traced an abnormal proliferation of stem cells to a naturally occurring mutation that arose hundreds of years ago in a gene called CLAVATA3. Selection for this rare mutant by plant cultivators is the reason we have beefsteak tomatoes today.

In plants, like animals, stem cells give rise to the diversity of specialized cell types that comprise all tissues and organs. But too many stem cells can be a problem. In people, too many stem cells can lead to cancer. Similarly, when stem cell production goes unchecked in plants, growth becomes imbalanced and irregular, threatening survival.

The finely tuned balance of stem cell production in plants is controlled by genes that have opposite activities. Specifically, a gene known as WUSCHEL promotes stem cell formation, whereas CLAVATA genes inhibit stem cell production. Several genes in the CLAVATA family encode for receptor proteins that sit on the surface of plant cells -- the equivalent of locks -- as well as a series of proteins that dock at these receptors -- the equivalent of keys. When a CLAVATA key is made and fits in a CLAVATA lock, a signal is sent inside the cell that tells WUSCHEL to slow down. Critically, this prevents WUSCHEL from making too many stem cells.

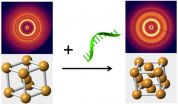

It is therefore no surprise that when CLAVATA genes are mutated, the plant makes too many stem cells in the meristem. However, in the newly reported experiments, Lippman's team examined never before studied mutant tomato plants, three of which contained faulty genes encoding enzymes that add sugar molecules to proteins. How was this discovery relevant to plant stem cells? Lippman's experiments revealed that the enzymes, called arabinosyltransfersases (ATs), add sugar molecules called arabinoses to CLAVATA3 -- one of the CLAVATA keys. Remarkably, these sugars are required for the key to fit a CLAVATA lock.

The team's important discovery: changing the number of sugars attached to the CLAVATA3 key can change the number of stem cells. Three sugars is normal, and produces normal growth. But when the one or more sugars on the CLAVATA3 key are missing, the key no longer fits properly in the lock. WUSCHEL therefore sends its signal to make new stem cells, but that message is not accompanied by a "stop" signal. There is abnormal growth; the plant's fruit becomes extremely large. Revisiting the original beefsteak tomato variety, Lippman and collaborator Esther van der Knaap at Ohio State University found that the secret of the beefsteak is that not enough of the CLAVATA3 key is made in the meristem. The result is too many stem cells and giant fruits.

The research more broadly shows that there is a continuum of growth possibilities in the tomato plant, and in other plants -- since the CLAVATA pathway is highly conserved in evolution and exists in all plants. By adjusting the number of sugars on CLAVATA keys, and through other mutations affecting components of the pathway, Lippman and colleagues show it is possible to fine-tune growth in ways that could allow breeders to customize fruit size.

INFORMATION:

The research discussed in this story was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Life Sciences Research Foundation, the Energy Biosciences Institute, DuPont Pioneer, the National Science Foundation, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

"A cascade of arabinosyltransferases controls shoot meristem size in tomato" appears May 25, 2015 in Nature Genetics. The authors are: Cao Xu, Katie L. Liberatore, Cora A. MacAlister, Zejun Huang, Yi-Hsuan Chu, Ke Jiang, Christopher Brooks,

Mari Ogawa-Ohnishi, Guangyan Xiong, Markus Pauly, Joyce Van Eck, Yoshikatsu Matsubayashi, Esther van der Knaap and Zachary B. Lippman. The paper can be obtained at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.3309 .

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Celebrating its 125th anniversary in 2015, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. Home to eight Nobel Prize winners, the private, not-for-profit Laboratory is more than 600 researchers and technicians strong. The Meetings & Courses Program hosts more than 12,000 scientists from around the world each year on its campuses in Long Island and in Suzhou, China. The Laboratory's education arm also includes an academic publishing house, a graduate school and programs for middle and high school students and teachers. For more information, visit http://www.cshl.edu

UPTON, NY -- Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory have just taken a big step toward the goal of engineering dynamic nanomaterials whose structure and associated properties can be switched on demand. In a paper appearing in Nature Materials, they describe a way to selectively rearrange the nanoparticles in three-dimensional arrays to produce different configurations, or phases, from the same nano-components.

"One of the goals in nanoparticle self-assembly has been to create structures by design," said Oleg Gang, who led the work ...

New research conducted in a rural community in Pakistan highlights the crucial role that essential fatty acids play in human brain growth and function.

A team co-led by the University of Exeter, working with experts in Singapore, has published findings in Nature Genetics which show that mutations in the protein Mfsd2a cause impaired brain development in humans. Mfsd2a is the transporter in the brain for a special type of fat called lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) -- which are composed of essential fatty acids like omega-3. This shows the crucial role of these fats in ...

Having a healthy gut may well depend on maintaining a complex signaling dance between immune cells and the stem cells that line the intestine. Scientists at the Buck Institute are now reporting significant new insight into how these complex interactions control intestinal regeneration after a bacterial infection. It's a dance that ensures repair after a challenge, but that also goes awry in aging fruit flies -- the work thus offers important new clues into the potential causes of age-related human maladies, such as irritable bowel syndrome, leaky gut and colorectal cancer.

"We've ...

May 26, 2015, Shenzhen, China - Researchers from BGI reported the most complete haploid-resolved diploid genome (HDG) sequence based on de novo assembly with NGS technology and the pipeline developed lays the foundation for de novo assembly of genomes with high levels of heterozygosity. The latest study was published online today in Nature Biotechnology.

The human genome is diploid, and knowledge of the variants on each chromosome is important for the interpretation of genomic information. In this study, researchers presented the assembly of a haplotype-resolved diploid ...

A gene essential to the production of pain-sensing neurons in humans has been identified by an international team of researchers co-led by the University of Cambridge. The discovery, reported today in the journal Nature Genetics, could have implications for the development of new methods of pain relief.

Pain perception is an evolutionarily-conserved warning mechanism that alerts us to dangers in the environment and to potential tissue damage. However, rare individuals - around one in a million people in the UK - are born unable to feel pain. These people accumulate numerous ...

Scientists at the University of York's Centre for Quantum Technology have made an important step in establishing scalable and secure high rate quantum networks.

Working with colleagues at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the University of Toronto, they have developed a protocol to achieve key-rates at metropolitan distances at three orders-of-magnitude higher than previously.

Standard protocols of Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) exploit random sequences of quantum bits (qubits) to distribute secret keys in a completely ...

TORONTO, May 25, 2015 - A new, Ontario-wide study shows that rates of hospital readmission following a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are greater than other chronic diseases and injuries and are higher than previously reported.

The study, led by Dr. Angela Colantonio, senior scientist, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, UHN, examined nearly 30,000 TBI patients discharged from Ontario hospitals over the span of eight years. Published in the May edition of Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the study found that about 36 per cent of patients with TBI had been ...

Madagascar is home to extraordinary biodiversity, but in the past few decades, the island's forests and associated biodiversity have been under greater attack than ever. Rapid deforestation is affecting the biotopes of hundreds of species, including the panther chameleon, a species with spectacular intra-specific colour variation. A new study by Michel Milinkovitch, professor of genetics, evolution, and biophysics at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), led in close collaboration with colleagues in Madagascar, reveals that this charismatic reptilian species, which is only ...

This news release is available in French. Certain blind individuals have the ability to use echoes from tongue or finger clicks to recognize objects in the distance, and some use echolocation as a replacement for vision. Research done by Dr. Mel Goodale, from the University of Western Ontario, in Canada, and colleagues around the world, is showing that echolocation in blind individuals is a full form of sensory substitution, and that blind echolocation experts recruit regions of the brain normally associated with visual perception when making echo-based assessments ...

Seville, Spain - 24 May 2015: Cognitive impairment predicts worse outcome in elderly heart failure patients, reveals research presented today at Heart Failure 2015 by Hiroshi Saito, a physiotherapist at Kameda Medical Centre in Kamogawa, Japan. Patients with cognitive impairment had a 7.5 times greater risk of call cause death and heart failure readmission.

Heart failure patients with cognitive impairment may get progressively worse at adhering to medications, leading to poorer prognosis.

Heart Failure 2015 is the main annual meeting of the Heart Failure Association ...