(Press-News.org) BOSTON, Aug. 17, 2015 -- A blood clot is a dangerous health situation with the potential to trigger heart attacks, strokes and other medical emergencies. To treat a blood clot, doctors need to find its exact location. But current clinical techniques can only look at one part of the body at a time, slowing treatment and increasing the risk for complications. Now, researchers are reporting a method, tested in rats, that may someday allow health care providers to quickly scan the entire body for a blood clot.

The team will describe their approach in one of more than 9,000 presentations at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society, taking place here through Thursday.

If a person suffers a stroke that stems from a blood clot, their risk for a second stroke skyrockets, says Peter Caravan, Ph.D. The initial blood clot can break apart and cause more strokes if it is not quickly found and treated. Depending on where the blood clot is located, the treatment varies -- some of them respond well to drugs, while others are better addressed with surgery.

To locate a blood clot, a physician may need to use three different methods: ultrasound to check the carotid arteries or legs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to scan the heart and computed tomography to view the lungs. "It's a shot in the dark," Caravan says. "Patients could end up being scanned multiple times by multiple techniques in order to locate a clot. We sought a method that could detect blood clots anywhere in the body with a single whole-body scan."

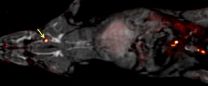

In previous work, Caravan's team at the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital identified a peptide that binds specifically to fibrin -- an insoluble protein fiber found in blood clots. In the current study, they developed a blood clot probe by attaching a radionuclide to the peptide. Radionuclides can be detected anywhere in the body by an imaging method called positron emission tomography (PET). The researchers used different radionuclides and peptides, as well as different chemical groups for linking the radionuclide to the peptide, to identify which combination would provide the brightest PET signal in blood clots. They ultimately constructed and tested 15 candidate blood clot probes.

The researchers first analyzed how well each probe bound to fibrin in a test tube, and then they studied how well the probe detected blood clots in rats. "The probes all had a similar affinity to fibrin in vitro, but, in rats, their performances were quite different," says Caravan. He attributed these differences to metabolism. Some probes were broken down quickly in the body and could no longer bind to blood clots, but others were resistant to metabolism. "The best probe was the one that was the most stable," he says. The team is moving forward into the next phase of research with this best-performing probe, called FBP8, which stands for "fibrin binding probe #8." It contained copper-64 as the radionuclide.

"Of course, the big question is, 'How well will these perform in patients?'" he says. Caravan explains that the group is hoping to start testing the probe in human patients in the fall, but it could take an additional five years of research before the probe is approved for routine use in a clinical setting.

A press conference on this topic will be held Tuesday, Aug. 18, at 2:30 p.m. Eastern time in the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center. Reporters may check-in at Room 153B in person, or watch live on YouTube http://bit.ly/ACSLiveBoston. To ask questions online, sign in with a Google account.

INFORMATION:

Caravan acknowledges funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; HL109448.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With more than 158,000 members, ACS is the world's largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note to journalists: Please report that this research is being presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Follow us: Twitter | Facebook

Title

Development of a fibrin-targeted radiopharmaceutical: effect of chelate type, linker, and radiometal on in vivo efficacy

Abstract

Thrombosis is often the underlying cause of major cardiovascular diseases including heart attack, stroke, and venous thromboembolism, which are leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Thrombus imaging would benefit from a whole-body approach instead of multiple examinations (current approach), especially for those cardiovascular events (e.g., thromboembolism) where the identification of both culprit embolus and source thrombus is required. We have been developing a fibrin-specific probe for thrombus detection by derivatizing a short, cyclic peptide that has high affinity and specificity for fibrin. We took an agnostic approach and compared different radionuclides (Cu-64, Ga-68, F-18, In-111, Tc-99m), different chelators, and different linkers. We characterized the affinity of the cold compound to fibrin and measured thrombus uptake, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and metabolism in a common rat model of arterial thrombosis. While all probes had similar affinity for fibrin, the in vivo studies showed a wide range of efficacy and these differences could be traced to differences in metabolic stability, either peptide metabolism or dechelation of the radiometal. There was no correlation of in vivo efficacy with in vitro measures of thermodynamic stability or kinetic inertness. Here we describe these structure-activity studies which led us to identify one specific probe for clinical translation.

BOSTON, Aug.17, 2015 -- In a first-of-its-kind study, researchers have determined that natural sunlight triggers the release of smog-forming nitrogen oxide compounds from the grime that typically coats buildings, statues and other outdoor surfaces in urban areas. The finding confirms previous laboratory work using simulated sunlight and upends the long-held notion that nitrates in urban grime are "locked" in place.

The scientists will present their findings based on field studies conducted in Leipzig, Germany, and Toronto, Canada, at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition ...

New Internet-based technology may aid criminal justice agencies through tools such as better criminal databases, remotely conducted criminal trials and electronic monitoring of parolees in the community, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Top criminal justice priorities for new Internet tools include developing a common criminal history record that can be shared across agencies, developing real-time language translation tools and improved video displays for law enforcement officers to adapt to changing needs, according to the analysis.

"The criminal justice ...

During the deer's breeding season, or rut, the researchers from Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) and ETH Zürich, played male fallow deer (bucks) in Petworth Park in West Sussex, a variety of different calls that had been digitally manipulated to change the pitch and length and analysed their responses. The bucks treated lower pitched and longer calls as more threatening, by looking towards source of the call sooner and for longer, than others.

Fallow bucks attracted the attention of the researchers because of their intriguing calling behaviour. Males are silent ...

BOSTON, Aug. 16, 2015 -- Sunlight can be brutal. It wears down even the strongest structures, including rooftops and naval ships, and it heats up metal slides and bleachers until they're too hot to use. To fend off damage and heat from the sun's harsh rays, scientists have developed a new, environmentally friendly paint out of glass that bounces sunlight off metal surfaces -- keeping them cool and durable.

The researchers present their work today at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS, the world's largest scientific ...

Findings from Nationwide Children's Hospital physicians demonstrate that headaches increase in fall in children, a trend that may be due to back-to-school changes in stress, routines and sleep. Although it may be difficult for parents to decipher a real headache from a child just wanting to hold onto summer a little longer and avoid going back to school, there is a variety of other common triggers including poor hydration and prolonged screen time that could contribute to a child's discomfort.

"When we saw many of our families and patients in clinic, the families would ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. - Medicare Part D provides help to beneficiaries struggling with the cost of prescriptions drugs, but the plan's coverage gap hits some populations harder than others, particularly African-Americans age 65 and older. Reaching, or even approaching, the gap affects access to medication and influences whether those medications are taken as prescribed.

"Don't assume that the existence of Part D means that people aren't having a difficult time affording their meds," says Louanne Bakk, an assistant professor in the University at Buffalo School of Social Work. "There ...

SALT LAKE CITY, Aug. 14, 2015 - Software may appear to operate without bias because it strictly uses computer code to reach conclusions. That's why many companies use algorithms to help weed out job applicants when hiring for a new position.

But a team of computer scientists from the University of Utah, University of Arizona and Haverford College in Pennsylvania have discovered a way to find out if an algorithm used for hiring decisions, loan approvals and comparably weighty tasks could be biased like a human being.

The researchers, led by Suresh Venkatasubramanian, ...

Discovered in 1982, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a disease-causing bacterium that survives in our stomachs despite the harsh acidic conditions. It is estimated that one in two people have got it, though most won't ever experience any problems. Even so, it is considered one of the most common bacterial infections worldwide and a leading cause of dyspepsia, peptic ulceration and gastric cancer.

Through unique evolutionary adaptations, H. pylori is able to evade the antiseptic effect of our stomach acid by hiding within the thick acid-resistant layer of mucus that ...

Washington, DC - August 14, 2015 - Tungsten is exceptionally rare in biological systems. Thus, it came as a huge surprise to Michael Adams, PhD., and his collaborators when they discovered it in what appeared to be a novel enzyme in the hot spring-inhabiting bacterium, Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. The researchers hypothesized that this new tungstoenzyme plays a key role in C. bescii's primary metabolism, and its ability to convert plant biomass to simple fermentable sugars. This discovery could ultimately lead to commercially viable conversion of cellulosic (woody) biomass ...

What happens when a drought in Florida estuaries causes a rise in the salt levels in water? Fewer wild oysters appear on restaurant menus, for starters.

New research from Northeastern University marine and environmental sciences professor David Kimbro and graduate student Hanna Garland, published in PLOS ONE, links the deterioration of oyster reefs in Florida's Matanzas River Estuary (MRE) to a population outbreak of carnivorous conchs and ...