(Press-News.org) ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Low-risk cancers that do not have any symptoms and presumably will not cause problems in the future are responsible for the rapid increase in the number of new cases of thyroid cancer diagnosed over the past decade, according to a Mayo Clinic study published in the journal Thyroid. According to the study authors, nearly one-third of these recent cases were diagnosed when clinicians used high-tech imaging even when no symptoms of thyroid disease were present.

"We are spotting more cancers, but they are cancers that are not likely to cause harm," says the study's lead author, Juan Brito Campana, M.B.B.S., an assistant professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic. "Their treatment, however, is likely to cause harm, as most thyroid cancers are treated by surgically removing all or part of the thyroid gland. This is a risky procedure that can damage a patient's vocal cords or leave them with lifelong calcium deficiencies."

Dr. Brito says harm is not limited to physical suffering. "Treatment can cause financial hardship for patients and their families and for society as a whole, as millions of dollars are spent for unnecessary and problematic surgeries," he says.

According to Dr. Brito, the aggregate national cost these procedures in the U.S. was $1.6 billion in 2013 and likely will exceed $3.5 billion by 2030. At the same time, the incidence of thyroid cancer is increasing more rapidly than that of any other cancer and is on track to become the third most common cancer in women.

In this study, Dr. Brito and his colleagues drew on data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. They analyzed the records of 566 men and women who were diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between 1935 and 2012. Specifically, they examined the number of new cases of thyroid cancer, the deaths due to the disease, and the method of diagnosis.

Researchers found that the number of new cases of thyroid cancer doubled in recent years - from 7.1 per 100,000 people from 1990 to 1999 to 13.7 per 100,000 people from 2000 to 2012. Over the same period, the number of new patients with thyroid cancer presenting with symptoms of thyroid cancer remained the same. In contrast, the number of new cases of silent thyroid cancer - the kind where patients have no symptoms - almost quadrupled. The proportion of patients with thyroid cancer who die of the disease has not changed since 1935.

The study found that the most frequent reasons for identifying silent thyroid cancer were review of thyroid tissue removed for benign conditions (14 percent); incidental discovery during an imaging test (19 percent); and investigations of patients with symptoms or palpable nodules that were clearly not associated with thyroid cancer, but triggered the use of imaging tests of the neck (27 percent).

"We are facing an epidemic of diagnosis in thyroid cancer," says Dr. Brito. "Now that we know where all these new cases are coming from, we can design strategies to identify patients with thyroid cancer who can benefit from our treatment without condemning other patients to unnecessary tests, treatment, suffering, and costs."

Researchers say one approach to curtail the detection of these lesions would be to limit the use of certain imaging technologies. Another tactic would be to engage patients in deliberating their treatment options. In many cases, active surveillance may be preferred over surgery by patients with small, relatively benign cancers that could take decades to grow to any appreciable size or cause life-threatening problems.

Dr. Brito thinks something as simple as not using the word "cancer" to refer to these small and silent thyroid lesions could reduce the number of unnecessary treatments for patients with a more favorable prognosis. Rather than calling these lesions thyroid cancer, he would recommend a less emotionally charged term, such as papillary lesions of indolent course.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Alaa Al Nofal, M.D., Victor Montori, M.D., Ian Hay, M.D., Ph.D., and John Morris III, M.D. - all of Mayo Clinic.

The study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R01AG034676).

About Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit worldwide leader in medical care, research and education for people from all walks of life. For more information, visit http://www.mayoclinic.org and http://www.mayoclinic.org/news.

MEDIA CONTACT:

Joe Dangor, Mayo Clinic Public Affairs, 507-284-5005, newsbureau@mayo.edu

This news release is available in French. Chemical substances that are safe for humans when taken in isolation can become harmful when they are combined. Three research teams bringing together researchers from Inserm and CNRS in Montpellier have elucidated in vitro a molecular mechanism that could contribute to the phenomenon known as the "cocktail effect." This study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Every day we are exposed to many exogenous compounds such as environmental pollutants, drugs or substances in our diet. Some of these molecules, known ...

Got rope? Then try this experiment: Cross both ends, left over right, then bring the left end under and out, as if tying a pair of shoelaces. If you repeat this sequence, you get what's called a "granny" knot. If, instead, you cross both ends again, this time right over left, you've created a sturdier "reef" knot.

The configuration, or "topology," of a knot determines its stiffness. For example, a granny knot is much easier to undo, as its configuration of twists creates weaker forces within the knot, compared with a reef knot. For centuries, sailors have observed such ...

WORCESTER, MA -- Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School are the first to show that it's possible to reverse the behavior of an animal by flipping a switch in neuronal communication. The research, published in PLOS Biology, provides a new approach for studying the neural circuits that govern behavior and has important implications for how scientists think about neural connectomes.

New technologies have fueled the quest to map all the neural connections in the brain to understand how these networks processes information and control behavior. The human ...

SALT LAKE CITY, Sept. 7, 2015 - If you are in a special relationship with another person, thank grandma - not just yours, but all grandmothers since humans evolved.

University of Utah anthropologist Kristen Hawkes is known for the "grandmother hypothesis," which credits prehistoric grandmothering for our long human lifespan. Now, Hawkes has used computer simulations to link grandmothering and longevity to a surplus of older fertile men and, in turn, to the male tendency to guard a female mate from the competition and form a "pair bond" with her instead of mating with ...

Physicists from the Department of Nanophotonics and Metamaterials at ITMO University have experimentally demonstrated the feasibility of designing an optical analog of a transistor based on a single silicon nanoparticle. Because transistors are some of the most fundamental components of computing circuits, the results of the study have crucial importance for the development of optical computers, where transistors must be very small and ultrafast at the same time. The study was published in the scientific journal Nano Letters.

The performance of modern computers, which ...

Developing transparent or semitransparent solar cells with high efficiency and low cost to replace the existing opaque and expensive silicon-based solar panels has become increasingly important due to the increasing demands of the building integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) systems. The Department of Applied Physics of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) has successfully developed efficient and low-cost semitransparent perovskite solar cells with graphene electrodes. The power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of this novel invention are around 12% when they are illuminated ...

Calculation with electron spins in a quantum computer assumes that the spin states last for a sufficient period of time. Physicists at the University of Basel and the Swiss Nanoscience Institute have now demonstrated that electron exchange in quantum dots fundamentally limits the stability of this information. Control of this exchange process paves the way for further progress in the coherence of the fragile quantum states. The report from the Basel-based researchers appears in the scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

The basic idea of a quantum computer is to ...

DENVER, Colo. -- The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) today issued a new statement on Tobacco Control and Smoking Cessation at the 16th World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC) in Denver. The statement calls for higher taxes on tobacco products, comprehensive advertising and promotion bans of all tobacco products and product regulation including pack warnings.

"Tax policies that increased the cost of cigarettes have played a prominent role in the reduction of cigarette smoking," said Dr. Kenneth Michael Cummings, Professor, Hollings Cancer ...

Scientists studying funnel-web spiders at Booderee National Park near Jervis Bay on the New South Wales south coast have found a large example of an unexpected funnel-web species.

The scientists believe the 50-millimetre spider is a species of the tree-dwelling genus Hadronyche, not the ground-dwelling genus Atrax, which includes the Sydney funnel-web, the only species reported in the Park's records.

"It's remarkable that we have found this other species in Booderee National Park," said Dr Thomas Wallenius, from The Australian National University (ANU).

"It shows ...

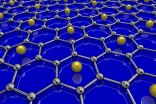

Graphene, the ultra-thin, ultra-strong material made from a single layer of carbon atoms, just got a little more extreme. University of British Columbia (UBC) physicists have been able to create the first ever superconducting graphene sample by coating it with lithium atoms.

Although superconductivity has already been observed in intercalated bulk graphite--three-dimensional crystals layered with alkali metal atoms, based on the graphite used in pencils--inducing superconductivity in single-layer graphene has until now eluded scientists.

"This first experimental realization ...