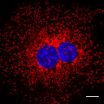

(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, Calif., December 23, 2010 – Melanoma is one of the least common types of skin cancer, but it is also the most deadly. Melanocytes (pigment-producing skin cells) lose the genetic regulatory mechanisms that normally limit their number, allowing them to divide and proliferate out of control. One such regulator, called MITF, controls an array of genes that influence melanocyte development, function and survival. Researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) and their collaborators recently used a melanoma mouse model, cell cultures and human tissue samples to unravel the relationship between MITF and ATF2, a transcription factor (or protein that controls gene expression) that is more active in melanomas. The study, published December 23 in PLoS Genetics, demonstrates that the MITF is subject to negative regulation by ATF2, and such regulation is a key determinant in melanoma development. This work also reveals that the ratio of ATF2 to MITF in the nucleus of melanoma cells can predict survival in melanoma patients – relatively high amounts of ATF2 and correspondingly low MITF levels were associated with a poor prognosis.

"In the late 1990s, we began to observe that if you can inhibit ATF2, you can inhibit melanoma," explained Ze'ev Ronai, Ph.D., senior author of the study and associate director of Sanford-Burnham's National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center. "This latest study provides the first genetic evidence to support those initial observations. Here we show that mice lacking ATF2 in melanocytes do not develop melanoma even if they carry mutations seen in human melanoma. Moreover, ATF2 expression patterns can predict outcome in melanoma patients."

In this study, Dr. Ronai and collaborators from five medical centers in the U.S. and U.K. disrupted the ATF2 gene in the melanocytes of mice harboring mutations often seen in human melanoma. It turns out that ATF2 blocks MITF function in the early stages of melanocyte development. Without ATF2's foot on the brake in these mice, melanoma was inhibited thanks to its affect on MITF expression.

To determine exactly how ATF2 keeps the damper on MITF, the researchers then drilled down to melanocytes and melanoma cells in a dish. In about half the cell lines tested, they noted that ATF2's control over MITF is indirect – ATF2 actually controls a protein, called SOX10, which is in turn necessary for MITF expression. While this control was sustained in melanocytes and 50 percent of melanomas, the other half of melanoma cell lines circumvented this pathway altogether. With this knowledge, the researchers found they could induce or inhibit melanoma development by artificially manipulating ATF2 and MITF levels.

Dr. Ronai's research team also looked at an array of more than 500 human melanoma samples. Some of the samples were from primary melanomas, while others were taken from metastatic melanoma. Comparing the relative levels of these transcription factors to the ultimate outcome known for each patient, they determined that a high ratio of ATF2 to MITF was associated with metastatic disease and decreased 10-year survival in patients. This provides a potential prognostic tool for identifying those patients whose melanomas are more likely to metastasize to other organs.

"This study focused on MITF, but that's probably not the only story. I believe we will continue to find more factors modulated by ATF2 in melanoma," said Anindita Bhoumik, one of the study's first authors. "There are still many studies to be done, but this will help us better understand the different signaling pathways important to melanoma development, with the ultimate goal of discovering new therapies."

### This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). For more information about Sanford-Burnham research, visit http://beaker.sanfordburnham.org.

Original paper

Shah M, Bhoumik A, Goel V, Dewing A, Breitwieser W, Kluger H, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, DeHart J, Lau E, Kallenberg DM, Jeong H, Eroshkin A, Bennett DC, Chin L, Bosenberg M, Jones N, Ronai ZA. A role for ATF2 in regulating MITF and melanoma development. PLoS Genetics. December 23, 2010.

About Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute

Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute is dedicated to discovering the fundamental molecular causes of disease and devising the innovative therapies of tomorrow. Sanford-Burnham, with operations in California and Florida, is one of the fastest-growing research institutes in the country. The Institute ranks among the top independent research institutions nationally for NIH grant funding and among the top organizations worldwide for its research impact. From 1999 – 2009, Sanford-Burnham ranked #1 worldwide among all types of organizations in the fields of biology and biochemistry for the impact of its research publications, defined by citations per publication, according to the Institute for Scientific Information. According to government statistics, Sanford-Burnham ranks #2 nationally among all organizations in capital efficiency of generating patents, defined by the number of patents issued per grant dollars awarded.

Sanford-Burnham utilizes a unique, collaborative approach to medical research and has established major research programs in cancer, neurodegeneration, diabetes, and infectious, inflammatory, and childhood diseases. The Institute is especially known for its world-class capabilities in stem cell research and drug discovery technologies. Sanford-Burnham is a nonprofit public benefit corporation. For more information, please visit www.sanfordburnham.org.

END

Tomato plants use similar biochemical mechanisms to reject pollen from their own flowers as well as pollen from foreign but related plant species, thus guarding against both inbreeding and cross-species hybridization, report plant scientists at the University of California, Davis.

The researchers identified a tomato pollen gene that encodes a protein that is very similar to a protein thought to function in preventing self-pollination in petunias. The tomato gene also was shown to play a role in blocking cross-species fertilization, suggesting that similar biochemical ...

BOSTON--By tweaking a single gene, scientists have mimicked in sedentary mice the heart-strengthening effects of two weeks of endurance training, according to a report from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC).

The genetic manipulation spurred the animals' heart muscle cells -- called cardiomyocytes -- to proliferate and grow larger by an amount comparable to normal mice that swam for up to three hours a day, the authors write in the journal Cell.

This specific gene manipulation can't be done in humans, they say, but the findings ...

Use of electronic health records by hospitals across the United States has had only a limited effect on improving the quality of medical care, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Studying a wide mix of hospitals nationally, researchers found that hospitals with basic electronic health records demonstrated a significantly higher increase in quality of care for patients being treated for heart failure.

However, similar gains were not noted among hospitals that upgraded to advanced electronic health records, and hospitals with electronic health records did not ...

LA JOLLA, CA—Researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have discovered how AMPK, a metabolic master switch that springs into gear when cells run low on energy, revs up a cellular recycling program to free up essential molecular building blocks in times of need.

In a paper published in the Dec. 23, 2010 edition of Science Express, a team led by Reuben Shaw, PhD., Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist and Hearst Endowment assistant professor in the Salk's Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, reports that AMPK activates a cellular recycling ...

Phosphorous levels plummet in kidney disease patients who stick to a vegetarian diet, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society Nephrology (CJASN). The results suggest that eating vegetables rather than meat can help kidney disease patients avoid accumulating toxic levels of this mineral in their bodies.

Individuals with kidney disease cannot adequately rid the body of phosphorus, which is found in dietary proteins and is a common food additive. Kidney disease patients must limit their phosphorous intake, as high ...

WORCESTER, Mass. — Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and the University of Texas at Austin have uncovered evidence that environmental influences experienced by a father can be passed down to the next generation, "reprogramming" how genes function in offspring. A new study published this week in Cell shows that environmental cues—in this case, diet—influence genes in mammals from one generation to the next, evidence that until now has been sparse. These insights, coupled with previous human epidemiological studies, suggest that paternal environmental ...

The cell signaling pathway known as Wnt, commonly activated in cancers, causes internal membranes within a healthy cell to imprison an enzyme that is vital in degrading proteins, preventing the enzyme from doing its job and affecting the stability of many proteins within the cell, researchers at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have found.

The finding is important because sequestering the enzyme, Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3), results in the stabilization of proteins in the cell, at least one of which is known to be a key player in cancer, said Dr. Edward ...

FINDINGS: Whitehead Institute researchers have determined that heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) can create diverse heritable traits in brewer's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) by affecting a large portion of the yeast genome. The finding has led the researchers to conclude that Hsp90 has played a key role in shaping the evolutionary history of the yeast genome, and likely others as well.

RELEVANCE: Over the past several years, Whitehead Member Susan Lindquist has built the case that heat shock proteins (Hsps), which are found across species from bacteria to humans, are ...

When prowling for a hook up, it's not always the good-looker who gets the girl. In fact, in a certain species of South American fish, brawn and stealth beat out colorful and refined almost every time.

In a series of published studies of a South American species of fish (Poecilia parae), which are closely related to guppies, Syracuse University scientists have discovered how the interplay between male mating strategies and predator behavior has helped preserve the population's distinctive color diversity over the course of time. The third study in the series was published ...

Scientists from the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at Delft University of Technology and Eindhoven University of Technology in The Netherlands have succeeded in controlling the building blocks of a future super-fast quantum computer. They are now able to manipulate these building blocks (qubits) with electrical rather than magnetic fields, as has been the common practice up till now. They have also been able to embed these qubits into semiconductor nanowires. The scientists' findings have been published in the current issue of the science journal Nature (23 December). ...