(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

If a restaurant owner fails to pay the protection money demanded of him, he can expect his premises to be trashed. Warnings like these are seldom required, however, as fear of the consequences is enough to make restaurant owners pay up. Similarly, mafia-like behaviour is observed in parasitic birds, which lay their eggs in other birds' nests. If the host birds throw the cuckoo's egg out, the brood parasites take their revenge by destroying the entire nest. Consequently, it is beneficial for hosts to be capable of learning and to cooperate. Previously seen only in field observations, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön have now modelled this behaviour mathematically to confirm it as an effective strategy.

Some parasitic birds, such as the North American brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater), are observed to punish host birds by destroying their clutches if their eggs are rejected. Consequently, the hosts accept a certain degree of parasitism as long as they can raise their own offspring alongside the parasitic chicks. "We tested and confirmed the mafia hypothesis, which was controversial among scientists," explains Maria Abou Chakra, lead author of the study. The parasitic birds use their behaviour to extort the hosts, forcing them to cooperate. "They give the hosts no choice. If they wish to avoid retaliation, they need to keep the foreign egg."

For the theory to work, two points are absolutely crucial: the host birds must be capable of learning, and the parasites must approach the same nests more than once. Only then does the mafia-like behaviour have the desired effect. "For the hosts, the best thing is to remove the foreign egg from their own nests. But if they encounter a retaliatory parasite that destroys their nest, it's best to adapt and accept the parasitic egg," says Abou Chakra.

Maria Abou Chakra works in the Evolutionary Theory Department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology. In collaboration with Christian Hilbe, now at Harvard University, and Arne Traulsen, she developed mathematical models to test the mafia hypothesis. The underlying principle in their minimalistic model was that each parasite lays no more than one egg in another bird's nest, which the host may accept or eject. A more complex model allowed the parasites to lay several eggs, each of which could be destroyed or accepted individually.

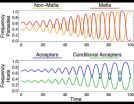

"Biologists prefer the complex model, because it is closer to reality. But we came to the same conclusion with both models: the dynamics of the interaction between host and parasite is cyclical." An equilibrium is never established; instead, there are regular cycles in terms of the frequency of mafia and non-mafia parasites and hosts that accept an egg immediately or only after they have suffered retaliation. If the number of non-mafia brood parasites is high, the advantage lies with conditional accepters, hosts that leave the parasite's egg in their nest only after their nest has been destroyed. After all, there is little chance the parasite is a retaliator. This behaviour therefore increases among host birds. And this, in turn, improves the survival rate of the mafia-like brood parasites. As soon as the latter are in the majority, it makes sense for the hosts to accept unconditionally, which, in turn, renders the mafia-like behaviour unnecessary. The cycle begins anew.

Evolutionary biologist Amotz Zahavi postulated the mafia hypothesis back in 1979. It has been contentious ever since. Critics argue that the retaliation gives the parasites no advantage, carrying high costs instead. However, the future nestlings benefit from the hot-headed behaviour if the host parents do indeed keep and hatch the next cuckoo's egg for fear of having their nest destroyed again.

Instead of retaliating, the parasites could attempt to mimic the eggs of the host birds. This makes it more difficult for hosts to identify and destroy the foreign egg. There are some birds which do in fact apply this strategy. But Abou Chakra sees an advantage in the mafia-like behaviour itself: "We believe it helps the parasites to avoid specialisation." Birds that do not adapt the size and colour of their eggs to any particular host can foist their offspring on nearly any species of bird and use their behaviour to force the foster parents to raise it. "The question is, what are the conditions under which it's better for parasites to specialise and when does mafia-like behaviour pay off?" This is what the scientists intend on testing next.

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Maria Abou Chakra, Christian Hilbe & Arne Traulsen

Plastic behaviors in hosts promote the emergence of retaliatory parasites

Scientific Reports, 4 March 2014; doi:10.1038/srep04251

Fear of the cuckoo mafia

For fear of retaliation, birds accept and raise brood parasites' young

2014-04-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

East African honeybees are safe from invasive pests… for now

2014-04-17

Several parasites and pathogens that devastate honeybees in Europe, Asia and the United States are spreading across East Africa, but do not appear to be impacting native honeybee populations at this time, according to an international team of researchers.

The invasive pests include including Nosema microsporidia and Varroa mites.

"Our East African honeybees appear to be resilient to these invasive pests, which suggests to us that the chemicals used to control pests in Europe, Asia and the United States currently are not necessary in East Africa," said Elliud Muli, senior ...

Drought and fire in the Amazon lead to sharp increases in forest tree mortality

2014-04-17

Ongoing deforestation and fragmentation of forests in the Amazon help create tinderbox conditions for wildfires in remnant forests, contributing to rapid and widespread forest loss during drought years, according to a team of researchers.

The findings show that forests in the Amazon could reach a "tipping point" when severe droughts coupled with forest fires lead to large-scale loss of trees, making recovery more difficult, said Jennifer Balch, assistant professor of geography, Penn State.

"We documented one of the highest tree mortality rates witnessed in Amazon forests," ...

Classifying cognitive styles across disciplines

2014-04-17

Educators have tried to boost learning by focusing on differences in learning styles. Management consultants tout the impact that different decision-making styles have on productivity. Various fields have developed diverse approaches to understanding the way people process information. A new report from psychological scientists aims to integrate these disciplines by offering a new, integrated framework of cognitive styles that bridges different terminologies, concepts, and approaches.

"This new taxonomy of cognitive styles offers a clear categorization of different types ...

Unraveling the 'black ribbon' around lung cancer

2014-04-17

It's not uncommon these days to find a colored ribbon representing a disease. A pink ribbon is well known to signify breast cancer. But what color ribbon does one think of with lung cancer?

Although white has been identified as the designated color, for many suffering from the disease, black may be the only one they think fits.

A Michigan State University study consisting of lung cancer patients, primarily smokers between the ages of 51 to 79 years old, is shedding more light on the stigma often felt by these patients, the emotional toll it can have and how health providers ...

Some immune cells defend only 1 organ

2014-04-17

Scientists have uncovered a new way the immune system may fight cancers and viral infections. The finding could aid efforts to use immune cells to treat illness.

The research, in mice, suggests that some organs have the immunological equivalent of "neighborhood police" – specialized squads of defenders that patrol only one area, a single organ, instead of an entire city, the body.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that the liver, skin and uterus each has dedicated immune cells, which they call tissue-resident natural killer ...

Deaths from viral hepatitis surpasses HIV/AIDS as preventable cause of deaths in Australia

2014-04-17

The analysis was conducted by Dr Benjamin Cowie and Ms Jennifer MacLachlan from the University of Melbourne and Melbourne Health, and was presented at The International Liver Congress in London earlier this month.

"Liver cancer is the fastest increasing cause of cancer deaths in Australia, increasing each year by 5 per cent, so by more than seventy people each year. In 2014 there was an estimated number of deaths of around 1,500 from liver cancer. The predominant cause is chronic viral Hepatitis," Dr Cowie said.

Hepatitis refers to the inflammation of the liver. Chronic ...

Ancient sea-levels give new clues on ice ages

2014-04-17

International researchers, led by the Australian National University (ANU), have developed a new way to determine sea-level changes and deep-sea temperature variability over the past 5.3 million years.

The findings will help scientists better understand the climate surrounding ice ages over the past two million years, and could help determine the relationship between carbon dioxide levels, global temperatures and sea levels.

The team from ANU, the University of Southampton (UoS) and the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) in the United Kingdom, examined oxygen isotope ...

Scientists find new way to fight malaria drug resistance

2014-04-17

An anti-malarial treatment that lost its status as the leading weapon against the deadly disease could be given a new lease of life, with new research indicating it simply needs to be administered differently.

The findings could revive the use of the cheap anti-malarial drug chloroquine in treating and preventing the mosquito-bourne disease, which claims the lives of more than half a million people each year around the world.

The parasite that causes malaria has developed resistance to chloroquine, but research carried out at the Australian National University (ANU) ...

Newlyweds, be careful what you wish for

2014-04-17

A statistical analysis of the gift "fulfillments" at several hundred online wedding gift registries suggests that wedding guests are caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to buying an appropriate gift for the happy couple. The details reported in the International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing suggest that most people hope to garner social benefits of buying an expensive gift that somehow enhances their relationship with the newlyweds while at the same time they wish to limit monetary cost and save money.

Yun Kyung Oh of the Department of ...

More research called for into HIV and schistosomiasis coinfection in African children

2014-04-17

Researchers from LSTM have called for more research to be carried out into HIV and schistosomiasis coinfection in children in sub-Saharan Africa. In a paper in The Lancet Infectious Diseases LSTM's Professor Russell Stothard, working with colleagues in the department of Parasitology and researchers from Cape Western Reserve University, in Cleveland Ohio, University of Cambridge and the Royal Veterinary College looked at previous research into the joint burden of HIV/AIDS and schistosomiasis of children, and found that while disease-specific control interventions are continuing, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A new reagent makes living brains transparent for deeper, non-invasive imaging

Smaller insects more likely to escape fish mouths

Failed experiment by Cambridge scientists leads to surprise drug development breakthrough

Salad packs a healthy punch to meet a growing Vitamin B12 need

Capsule technology opens new window into individual cells

We are not alone: Our Sun escaped together with stellar “twins” from galaxy center

Scientists find new way of measuring activity of cell editors that fuel cancer

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

AAN issues guidance on the use of wearable devices

In former college athletes, more concussions associated with worse brain health

Racial/ethnic disparities among people fatally shot by U.S. police vary across state lines

US gender differences in poverty rates may be associated with the varying burden of childcare

3D-printed robotic rattlesnake triggers an avoidance response in zoo animals, especially species which share their distribution with rattlers in nature

Simple ‘cocktail’ of amino acids dramatically boosts power of mRNA therapies and CRISPR gene editing

Johns Hopkins scientists engineer nanoparticles able to seek and destroy diseased immune cells

[Press-News.org] Fear of the cuckoo mafiaFor fear of retaliation, birds accept and raise brood parasites' young