(Press-News.org) Engineers like to make things that work. And if one wants to make something work using nanoscale components—the size of proteins, antibodies, and viruses—mimicking the behavior of cells is a good place to start since cells carry an enormous amount of information in a very tiny packet. As Erik Winfree, professor of computer science, computation and neutral systems, and bioengineering, explains, "I tend to think of cells as really small robots. Biology has programmed natural cells, but now engineers are starting to think about how we can program artificial cells. We want to program something about a micron in size, finer than the dimension of a human hair, that can interact with its chemical environment and carry out the spectrum of tasks that biological things do, but according to our instructions."

Getting tiny things to behave is, however, a daunting task. A central problem bioengineers face when working at this scale is that when biochemical circuits, such as the one Winfree has designed, are restricted to an extremely small volume, they may cease to function as expected, even though the circuit works well in a regular test tube. Smaller populations of molecules simply do not behave the same as larger populations of the same molecules, as a recent paper in Nature Chemistry demonstrates.

Winfree and his coauthors began their investigation of the effect of small sample size on biochemical processes with a biochemical oscillator designed in Winfree's lab at Caltech. This oscillator is a solution composed of small synthetic DNA molecules that are activated by RNA transcripts and enzymes. When the DNA molecules are activated by the other components in the solution, a biological circuit is created. This circuit fluoresces in a rhythmic pulse for approximately 15 hours until its chemical reactions slow and eventually stop.

The researchers then "compartmentalized" the oscillator by reducing it from one large system in a test tube to many tiny oscillators. Using an approach developed by Maximilian Weitz and colleagues at the Technical University of Munich and former Caltech graduate student Elisa Franco, currently an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UC Riverside, an aqueous solution of the DNA, RNA, and enzymes that make up the biochemical oscillator was mixed with oil and shaken until small portions of the solution, each containing a tiny oscillator, were isolated within droplets surrounded by oil.

"After the oil is added and shaken, the mixture turns into a cream, called an emulsion, that looks somewhat like a light mayonnaise," says Winfree. "We then take this cream, pour it on a glass slide and spread it out, and observe the patterns of pulsing fluorescence in each droplet under a microscope."

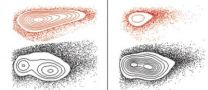

When a large sample of the solution is active, it fluoresces in regular pulses. The largest droplets behave as the entire solution does: fluorescing mostly in phase with one another, as though separate but still acting in concert. But the behavior of the smaller droplets was found to be much less consistent, and their pulses of fluorescence quickly moved out of phase with the larger droplets.

Researchers had expected that the various droplets, especially the smaller ones, would behave differently from one another due to an effect known as stochastic reaction dynamics. The specific reactions that make up a biochemical circuit may happen at slightly different times in different parts of a solution. If the solution sample is large enough, this effect is averaged out, but if the sample is very small, these slight differences in the timing of reactions will be amplified. The sensitivity to droplet size can be even more significant depending on the nature of the reactions. As Winfree explains, "If you have two competing reactions—say x could get converted to y, or x could get converted to z, each at the same rate—then if you have a test tube–sized sample, you will end up with a something that is half y and half z. But if you only have four molecules in a droplet, then perhaps they will all convert to y, and that's that: there's no z to be found."

In their experiments on the biochemical oscillator, however, Winfree and his colleagues discovered that this source of noise—stochastic reaction dynamics—was relatively small compared to a source of noise that they did not anticipate: partitioning effects. In other words, the molecules that were captured in each droplet were not exactly the same. Some droplets initially had more molecules, while others had fewer; also, the ratio between the various elements was different in different droplets. So even before the differential timing of reactions could create stochastic dynamics, these tiny populations of molecules started out with dissimilar features. The differences between them were then further amplified as the biochemical reactions proceeded.

"To make an artificial cell work," says Winfree, "you need to know what your sources of noise are. The dominant thought was that the noise you're confronted with when you're engineering nanometer-scale components has to do with randomness of chemical reactions at that scale. But this experience has taught us that these stochastic reaction dynamics are really the next-level challenge. To get to that next level, first we have to learn how to deal with partitioning noise."

For Winfree, this is an exciting challenge: "When I program my computer, I can think entirely in terms of deterministic processes. But when I try to engineer what is essentially a program at the molecular scale, I have to think in terms of probabilities and stochastic (random) processes. This is inherently more difficult, but I like challenges. And if we are ever to succeed in creating artificial cells, these are the sorts of problems we need to address."

INFORMATION:

Coauthors of the paper, "Diversity in the dynamical behaviour of a compartmentalized programmable biochemical oscillator," include Maximilian Weitz, Korbinian Kapsner, and Friedrich C. Simmel of the Technical University of Munich; Jongmin Kim of Caltech; and Elisa Franco of UC Riverside. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation, UC Riverside, the European Commission, the German Research Foundation Cluster of Excellence Nanosystems Initiative Munich, and the Elite Network of Bavaria.

Building artificial cells will be a noisy business

2014-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study evaluates role of infliximab in treating Kawasaki disease

2014-02-24

Kawasaki Disease (KD) is a severe childhood disease that many parents, even some doctors, mistake for an inconsequential viral infection. If not diagnosed or treated in time, it can lead to irreversible heart damage.

Signs of KD include prolonged fever associated with rash, red eyes, mouth, lips and tongue, and swollen hands and feet with peeling skin. The disease causes damage to the coronary arteries in a quarter of untreated children and may lead to serious heart problems in early adulthood. There is no diagnostic test for Kawasaki disease, and current treatment fails ...

Scientists complete the top quark puzzle

2014-02-24

Scientists on the CDF and DZero experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have announced that they have found the final predicted way of creating a top quark, completing a picture of this particle nearly 20 years in the making.

The two collaborations jointly announced on Friday, Feb. 21 that they had observed one of the rarest methods of producing the elementary particle – creating a single top quark through the weak nuclear force, in what is called the "s-channel." For this analysis, scientists from the CDF and DZero collaborations ...

As hubs for bees and pollinators, flowers may be crucial in disease transmission

2014-02-24

AMHERST, Mass. – Like a kindergarten or a busy airport where cold viruses and other germs circulate freely, flowers are common gathering places where pollinators such as bees and butterflies can pick up fungal, bacterial or viral infections that might be as benign as the sniffles or as debilitating as influenza.

But "almost nothing is known regarding how pathogens of pollinators are transmitted at flowers," postdoctoral researcher Scott McArt and Professor Lynn Adler at the University of Massachusetts Amherst write. "As major hubs of plant-animal interactions throughout ...

Mental health conditions in most suicide victims left undiagnosed at doctor visits

2014-02-24

VIDEO:

The mental health conditions of most people who commit suicide remain undiagnosed, even though many visit a primary care provider or medical specialist in the year before they die, according...

Click here for more information.

DETROIT – The mental health conditions of most people who commit suicide remain undiagnosed, even though many visit a primary care provider or medical specialist in the year before they die, according to a national study led by Henry Ford Health ...

Cancer patients turning to mass media and non-experts for info

2014-02-24

PHILADELPHIA (February 24, 2014) – The increasing use of expensive medical imaging procedures in the U.S. like positron emission tomography (PET) scans is being driven, in part, by patient decisions made after obtaining information from lay media and non-experts, and not from health care providers.

That is the result from a three-year-long analysis of survey data, and is published in the article , "Associations between Cancer-Related Information Seeking and Receiving PET Imaging for Routine Cancer Surveillance – An Analysis of Longitudinal Survey Data," appearing in ...

JCI early table of contents for Feb. 24, 2014

2014-02-24

PPAR-γ agonist reverses cigarette smoke induced emphysema in mice

Pulmonary emphysema results in irreversible lung damage and is most often the result of long term cigarette smoke exposure. Immune cells, such as macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) accumulate in the lungs of smokers with emphysema and release cytokines associated with autoimmune and inflammatory responses. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation Farrah Kheradmand and colleagues at Baylor University found that peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) ...

Mdm2 suppresses tumors by pulling the plug on glycolysis

2014-02-24

Cancer cells have long been known to have higher rates of the energy-generating metabolic pathway known as glycolysis. This enhanced glycolysis, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect, is thought to allow cancer cells to survive the oxygen-deficient conditions they experience in the center of solid tumors. A study in The Journal of Cell Biology reveals how damaged cells normally switch off glycolysis as they shut down and shows that defects in this process may contribute to the early stages of tumor development.

Various stresses can cause cells to cease proliferating ...

Two-pronged approach successfully targets DNA synthesis in leukemic cells

2014-02-24

A novel two-pronged strategy targeting DNA synthesis can treat leukemia in mice, according to a study in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Current treatments for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), an aggressive form of blood cancer, include conventional chemotherapy drugs that inhibit DNA synthesis. These drugs are effective but have serious side effects on normal dividing tissues.

In order to replicate, cells must make copies of their DNA, which is made up of building blocks called deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs). Cells can either make dNTPs from scratch ...

Blocking autophagy with malaria drug may help overcome resistance to melanoma BRAF drugs

2014-02-24

PHILADELPHIA— Half of melanoma patients with the BRAF mutation have a positive response to treatment with BRAF inhibitors, but nearly all of those patients develop resistance to the drugs and experience disease progression.

Now, a new preclinical study published online ahead of print in the Journal of Clinical Investigation from Penn Medicine researchers found that in many cases the root of the resistance may lie in a never-before-seen autophagy mechanism induced by the BRAF inhibitors vermurafenib and dabrafenib. Autophagy is a process by which cancer cells recycle ...

Like mom or dad? Some cells randomly express one parent's version of a gene over the other

2014-02-24

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – We are a product of our parents. Maybe you have your mother's large, dark eyes, and you inherited your father's infectious smile. Both parents contribute one copy, or allele, of each gene to their offspring, so that we have two copies of every gene for a given trait – one from mom, the other from dad. In general, both copies of a gene are switched on or off as an embryo develops into an adult. The "switching on" of a gene begins the process of gene expression that ultimately results in the production of a protein.

Occasionally, a cell will arbitrarily ...