(Press-News.org) BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University study in collaboration with medical researchers from Karolinska Institute in Stockholm has found that advancing paternal age at childbearing can lead to higher rates of psychiatric and academic problems in offspring than previously estimated.

Examining an immense data set -- everyone born in Sweden from 1973 until 2001 -- the researchers documented a compelling association between advancing paternal age at childbearing and numerous psychiatric disorders and educational problems in their children, including autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, suicide attempts and substance abuse problems. Academic problems included failing grades, low educational attainment and low IQ scores.

Among the findings: When compared to a child born to a 24-year-old father, a child born to a 45-year-old father is 3.5 times more likely to have autism, 13 times more likely to have ADHD, two times more likely to have a psychotic disorder, 25 times more likely to have bipolar disorder and 2.5 times more likely to have suicidal behavior or a substance abuse problem. For most of these problems, the likelihood of the disorder increased steadily with advancing paternal age, suggesting there is no particular paternal age at childbearing that suddenly becomes problematic.

"We were shocked by the findings," said Brian D'Onofrio, lead author and associate professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. "The specific associations with paternal age were much, much larger than in previous studies. In fact, we found that advancing paternal age was associated with greater risk for several problems, such as ADHD, suicide attempts and substance use problems, whereas traditional research designs suggested advancing paternal age may have diminished the rate at which these problems occur."

The study, "Parental Age at Childbearing and Offspring Psychiatric and Academic Morbidity," was published today (Feb. 26) in JAMA Psychiatry.

Notably, the researchers found converging evidence for the associations with advancing paternal age at childbearing from multiple research designs for a broad range of problems in offspring. By comparing siblings, which accounts for all factors that make children living in the same house similar, researchers discovered that the associations with advancing paternal age were much greater than estimates in the general population. By comparing cousins, including first-born cousins, the researchers could examine whether birth order or the influences of one sibling on another could account for the findings.

The authors also statistically controlled for parents' highest level of education and income, factors often thought to counteract the negative effects of advancing paternal age because older parents are more likely to be more mature and financially stable. The findings were remarkably consistent, however, as the specific associations with advancing paternal age remained.

"The findings in this study are more informative than many previous studies," D'Onofrio said. "First, we had the largest sample size for a study on paternal age. Second, we predicted numerous psychiatric and academic problems that are associated with significant impairment. Finally, we were able to estimate the association between paternal age at childbearing and these problems while comparing differentially exposed siblings, as well as cousins. These approaches allowed us to control for many factors that other studies could not."

In the past 40 years, the average age for childbearing has been increasing steadily for both men and women. Since 1970 for instance, the average age of first-time mothers in the U.S. has gone up four years from 21.5 to 25.4. For men the average is three years older. In the northeast, the ages are higher. Yet the implications of this fact -- both socially and in terms of the long-term effects on the health and well-being of the population as a whole -- are not yet fully understood.

Moreover, while maternal age has been under scrutiny for a number of years, a more recent body of research has begun to explore the possible effects of advancing paternal age on a variety of physical and mental health issues in offspring. Existing studies have pointed to increasing risks for some psychological disorders with advancing paternal age. Yet the results are often inconsistent with one another, statistically inconclusive or unable to take certain confounding factors into account.

The working hypothesis for D'Onofrio and his colleagues who study this phenomenon is that unlike women, who are born with all their eggs, men continue to produce new sperm throughout their lives. Each time sperm replicate, there is a chance for a mutation in the DNA to occur. As men age, they are also exposed to numerous environmental toxins, which have been shown to cause mutations in the DNA found in sperm. Molecular genetic studies have, in fact, shown that sperm of older men have more genetic mutations.

This study and others like it, however, perhaps signal some of the unforeseen, negative consequences of a relatively new trend in human history. As such, D'Onofrio said, it may have important social and public policy implications. Given the increased risk associated with advancing paternal age at childbearing, policy-makers may want to make it possible for men and women to accommodate children earlier in their lives without having to set aside other goals.

"While the findings do not indicate that every child born to an older father will have these problems," D'Onofrio said, "they add to a growing body of research indicating that advancing paternal age is associated with increased risk for serious problems. As such, the entire body of research can help to inform individuals in their personal and medical decision-making."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include research scientist Martin Rickert from the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, and Emma Frans, Ralf Kuja-Halkola, Catarina Almqvist, Arvid Sjolander, Henrik Larsson and Paul Lichtenstein from the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

The research was funded with grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Swedish Research Council, and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

D'Onofrio can be reached at 812-856-0843 and bmdonofr@indiana.edu. He is director of the Developmental Psychopathology Laboratory. For additional assistance, or a copy of the paper, contact Liz Rosdeitcher at 812-855-4507 or rosdeitc@indiana.edu, or Tracy James at 812-855-0084 or traljame@iu.edu.

IU study ties father's age to higher rates of psychiatric, academic problems in kids

2014-02-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Improved prescribing and reimbursement practices in China

2014-02-26

Bethesda, MD — Pay-for-performance—reimbursing health care providers based on the results they achieved with their patients as a way to improve quality and efficiency—has become a major component of health reforms in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other affluent countries. Although the approach has also become popular in the developing world, there has been little evaluation of its impact. A new study, being released today as a Web First by Health Affairs, examines the effects of pay-for-performance, combined with capitation, in China's largely rural Ningxia ...

3-D microgels 'on-demand' offer new potential for cell research

2014-02-26

Stars, diamonds, circles.

Rather than your average bowl of Lucky Charms, these are three-dimensional cell cultures generated by an exciting new digital microfluidics platform, the results of which have been published in Nature Communications this week by researchers at the University of Toronto. The tool, which can be used to study cells in cost-efficient, three-dimensional microgels, may hold the key to personalized medicine applications in the future.

"We already know that the microenvironment can greatly influence cell fate," says Irwin A. Eydelnant, recent doctoral ...

New gas-phase compounds form organic particle ingredients

2014-02-26

Helsinki/Jülich/Leipzig. Scientists made an important step in order to better understand the relationships between vegetation and climate. So-called extremely low-volatility organic compounds, which are produced by plants, could be detected for the first time during field and laboratory experiments in Finland and Germany. These organic species contribute to the formation of aerosol that can affect climate and air quality, they report in this week's issue of the journal Nature. The results may help to explain discrepancies between observations and theories about how volatile ...

Antidote can deactivate new form of heparin

2014-02-26

Low-molecular-weight heparin is commonly used in surgeries to prevent dangerous blood clots. But when patients experience the other extreme – uncontrolled bleeding – in response to low-molecular-weight heparin, there is no antidote.

Now researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have created a synthetic form of low-molecular-weight heparin that can be reversed if things go wrong and would be safer for patients with poor kidney function.

"When doctors talk to me about the kind of heparin they want to use during ...

Surge in designer drugs, tainted 'E' poses lethal risks

2014-02-26

In the span of a decade, Canada has gone from ecstasy importer to global supplier of the illegal party drug. At the same time, even newer designer highs—sometimes just a mouse-click away—are flooding the drug market faster than legislation can keep pace.

It's a worrying problem that University of Alberta researchers say requires more education to help Canadians understand the very real, deadly risks of designer drug use.

"The chemists who are making these drugs are coming up with about 10 new drugs per year; the legislation cannot keep up with the market," said Alan ...

Study shows why breastfed babies are so smart

2014-02-26

Loads of studies over the years have shown that children who were breastfed score higher on IQ tests and perform better in school, but the reason why remained unclear.

Is it the mother-baby bonding time, something in the milk itself or some unseen attribute of mothers who breastfeed their babies?

Now a new study by sociologists at Brigham Young University pinpoints two parenting skills as the real source of this cognitive boost: Responding to children's emotional cues and reading to children starting at 9 months of age. Breastfeeding mothers tend to do both of those ...

Still-fresh remnants of Exxon Valdez oil protected by boulders

2014-02-26

HONOLULU – Twenty-five years after the infamous Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, beaches on the Alaska Peninsula hundreds of kilometers from the incident still harbor small hidden pockets of surprisingly unchanged oil, according to new research being presented here today.

The focus of the study is to learn how oil persists long after a spill. Researchers presenting the work caution that the amount of oil being studied is a trace of what was originally spilled and that results from these sites cannot be simply extrapolated to the entire spill area.

The ...

Fox Chase researchers discover new mechanism of gene regulation

2014-02-26

In the cells of humans and other organisms, only a subset of genes are active at any given time, depending largely on the stage of life and the particular duties of the cell. Cells use different molecular mechanisms to orchestrate the activation and deactivation of genes as needed. One central mechanism is an intricate DNA packaging system that either shields genes from activation or exposes them for use.

In this system, the DNA strand, with its genes, is coiled around molecules known as histones, which themselves are assembled into larger entities called nucleosomes. ...

Harvested rainwater harbors pathogens

2014-02-26

South Africa has been financing domestic rainwater harvesting tanks in informal low-income settlements and rural areas in five of that nation's nine provinces. But pathogens inhabit such harvested rainwater, potentially posing a public health hazard, especially for children and immunocompromised individuals, according to a team from the University of Stellenbosch. The research was published ahead of print in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

International studies had indicated that harvested rainwater frequently harbors pathogens, and that, in light of the financing ...

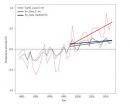

No warming hiatus for extreme hot temperatures

2014-02-26

Extremely hot temperatures over land have dramatically and unequivocally increased in number and area despite claims that the rise in global average temperatures has slowed over the past 10 to 20 years.

Scientists from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science and international colleagues made the finding when they focused their research on the rise of temperatures at the extreme end of the spectrum where impacts are felt the most.

"It quickly became clear, the so-called "hiatus" in global average temperatures did not stop the rise in the number, intensity ...