(Press-News.org) DURHAM, NC -- A protein that controls the metamorphosis of the common fruit fly could someday play a role in reversing brain injuries, said Duke University researchers.

This protein directs both the early development and regrowth of the tiny branches that relay information from neuron to neuron. Known as dendrites, these thin structures that resemble tree branches are responsible for receiving electrical impulses that flash throughout the body.

Incorrect dendrite development or injury has been linked to neurodevelopmental or psychiatric diseases in humans, such as autism, schizophrenia and fragile X syndrome.

Under normal circumstances, neural communication is easy, much like neighbors talking over a fence. But if a neuron is injured or malformed, they frequently don't have the proper dendrites needed to be functional.

"One of the major problems with the nervous system is that it doesn't regenerate very well after injury," said Chay Kuo, M.D., Ph.D., the George W. Brumley assistant professor of cell biology, neurobiology and pediatrics. "Neurons don't multiply, so when they're injured, there's a loss of function. We'd like to know how to get it back."

While prompting such regrowth in the human brain isn't currently possible, dendrite regeneration and arborization -- the branching out of dendrites from the body of the neuron -- are a necessary part of the fruit fly Drosophila's life cycle. In the larval (or worm) state, the fly's nervous system is attuned to what the smooth-skinned worm needs: finding food, locomotion and avoiding attack. As an adult with bristle-covered skin however, the nervous system must be wired for flying, finding mates and laying eggs.

Until now, researchers haven't understood how Drosophila sensory neurons are able to create two separate dendrite branching patterns that successfully serve different kinds of sensory environments, said Kuo, who is also a faculty member with the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences (DIBS). His team set out to find the genetic mechanism that makes it possible. This research, funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the George & Jean Brumley, Jr. Endowment, will appear online in the Feb. 27 issue of Cell Reports.

The answer lies in the insect's metamorphosis from larvae to adult. During this transition, Drosophila lose the neurons they won't need for adult life. The remaining sensory neurons sever their dendrites and grow a completely different set. The regeneration process, which is controlled by the hormone ecdysone, is much like pruning a tree in spring to make room for new growth, Kuo said.

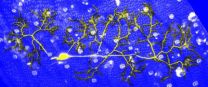

To find out how the drosophila sensory neurons accomplish this change, Kuo's team tagged abdominal sensory neurons with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and followed them through metamorphosis to see if their dendrite branching changed. The dendrite design and architecture was, in fact, different in the adult stage.

A test carried out by former graduate student Gray Lyons revealed Cysteine proteinase-1 (Cp1) is responsible for regulating the regeneration of neuron dendrites and innervating the adult sensory field. Kuo's team demonstrated that without Cp1, Drosophila sensory dendrites cannot regenerate after pruning.

Existing literature also pointed Kuo's team to a parallel between the drosophila nervous system and mammals.

"We investigated whether it was possible that Cp1, during metamorphosis, shuttles from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to cleave a transcription factor required for dendrite development, and makes it a new transcription factor for regeneration," Kuo said. "And, that turned out to be true."

The mammalian version of Cp1 is a protein known to be associated with cancer progression and other diseases called lysosomal protein capthesin-L (Ctsl). During the cell cycle, Ctsl can target a transcription factor – a protein that binds specific DNA sequences – called Cut-like 1 (Cux1) that plays a role in gene expression. Ctsl pursues Cux1 inside the nucleus and cleaves it, creating a smaller protein with different transcriptional properties than the original one.

"I feel this discovery is amazing because the major transcription factor involved in how fly sensory neurons grow dendrites in the first place is Cut, and Cut-like 1 is its mammalian homologue," Kuo said. "[Lyons'] initial idea looking into mammalian conservation for answers panned out big. It was serendipity."

By tagging Cut during Drosophila metamorphosis, Kuo's team observed the protein's binding pattern within the nucleus. Before dendrite pruning, Cut binds in big blobs. After the pruning, however, Cut binding is diffused, giving it an opportunity, Kuo said, to bind to different genes during the two dendrite growth phases.

The team translated this finding back to Cp1, discovering that it goes into the neuron nucleus to cleave Cut, making a new transcription factor required for dendrite regeneration after developmental pruning.

This research could also potentially impact how science and healthcare think about and treat brain injuries, Kuo said. Currently, damaged neurons that have lost their dendrites are unable to properly communicate with their neighbors, rendering them nonfunctional. The problem could be reversed, he said, by helping neurons modify their original developmental program and regrow new dendrites.

"If we can influence this environmental control that changes the development program, it's possible that we could get neurons to integrate and function better after injury," he said.

INFORMATION:

Kuo's co-authors include Gray R. Lyons, Ryan O. Andersen, Khadar Abdi, and Won-Seok Song from the Duke University School of Medicine.

CITATION: "Cysteine Proteinase-1 and Cut Protein Isoform Control Dendritic Innervation of Two Distinct Sensory Fields by a Single Neuron," Gray R. Lyons, Ryan O. Andersen, Khadar Abdi, Won-Seok Song, and Chay T. Kuo. Cell Reports, March 13, 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.003

Fruit fly's pruning protein could be key to treating brain injury

Single protein controls Drosophila nervous system development and survival

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

An ancient 'Great Leap Forward' for life in the open ocean

2014-02-27

It has long been believed that the appearance of complex multicellular life towards the end of the Precambrian (the geologic interval lasting up until 541 million years ago) was facilitated by an increase in oxygen, as revealed in the geological record. However, it has remained a mystery as to why oxygen increased at this particular time and what its relationship was to 'Snowball Earth' – the most extreme climatic changes the Earth has ever experienced – which were also taking place around then.

This new study shows that it could in fact be what was happening to nitrogen ...

Discoveries point to more powerful cancer treatments, fewer side effects

2014-02-27

What if there were a way to make chemotherapy and radiation more effective as cancer treatments than they are today, while also getting rid of debilitating side effects that patients dread? A new study led by Alexey Ryazanov, a professor of pharmacology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and member of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, suggests the day that happens could be getting closer.

Side effects such as heart damage, nausea and hair loss occur when cancer therapy kills healthy cells along with the malignant cells that are being targeted. It ...

A world free from cancers: Probable, possible, or preposterous?

2014-02-27

ALEXANDRIA, Va. – February 27, 2014 – A panel of leading health, economics and policy experts today discussed the prospects for a future where cancers are rendered manageable or even eradicated and the variables affecting progress toward that goal so that cancer patients are able to lead normal, productive lives – and thus be "free from" their cancers. The forum was hosted by Research!America and the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. The event, titled, "A World Free from Cancers: Probable, Possible, or Preposterous?" was held at the New York Academy of Sciences.

Medical ...

Math anxiety factors into understanding genetically modified food messages

2014-02-27

People who feel intimidated by math may be less able to understand messages about genetically modified foods and other health-related information, according to researchers.

"Math anxiety, which happens when people are worried or are concerned about using math or statistics, leads to less effort and decreases the ability to do math," said Roxanne Parrott, Distinguished Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and Health Policy and Administration. "Math anxiety also has been found to impair working memory."

The researchers found that math anxiety led to a decrease ...

Google Glass could help stop emerging public health threats around the world

2014-02-27

The much-talked-about Google Glass — the eyewear with computer capabilities — could potentially save lives, especially in isolated or far-flung locations, say scientists. They are reporting development of a Google Glass app that takes a picture of a diagnostic test strip and sends the data to computers, which then rapidly beam back a diagnostic report to the user. The information also could help researchers track the spread of diseases around the world. The study appears in the journal ACS Nano, a publication of the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific ...

Faster anthrax detection could speed bioterror response

2014-02-27

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Shortly following the 9/11 terror attack in 2001, letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to news outlets and government buildings killing five people and infecting 17 others. According to a 2012 report, the bioterrorism event cost $3.2 million in cleanup and decontamination. At the time, no testing system was in place that officials could use to screen the letters. Currently, first responders have tests that can provide a screen for dangerous materials in about 24-48 hours. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have worked with a private ...

Montreal researchers find a link between pollutants and certain complications of obesity

2014-02-27

Montréal, February 27, 2014 – A team of researchers at the IRCM in Montréal led by Rémi Rabasa-Lhoret, in collaboration with Jérôme Ruzzin from the University of Bergen in Norway, found a link between a type of pollutants and certain metabolic complications of obesity. Their breakthrough, published online this week by the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, could eventually help improve the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cardiometabolic risk associated with obesity, such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

Although obesity is strongly ...

Battery-free technology brings gesture recognition to all devices

2014-02-27

Mute the song playing on your smartphone in your pocket by flicking your index finger in the air, or pause your "This American Life" podcast with a small wave of the hand. This kind of gesture control for electronics could soon become an alternative to touchscreens and sensing technologies that consume a lot of power and only work when users can see their smartphones and tablets.

University of Washington computer scientists have built a low-cost gesture recognition system that runs without batteries and lets users control their electronic devices hidden from sight with ...

Bisphenol A (BPA) at very low levels can adversely affect developing organs in primates

2014-02-27

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical that is used in a wide variety of consumer products, such as resins used to line metal food and beverage containers, thermal paper store receipts, and dental composites. BPA exhibits hormone-like properties, and exposure of fetuses, infants, children or adults to the chemical has been shown to cause numerous abnormalities, including cancer, as well as reproductive, immune and brain-behavior problems in rodents. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have determined that daily exposure to very low concentrations of ...

Household wealth still down 14 percent since recession

2014-02-27

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Household wealth for Americans still has not recovered from the recession, despite last summer's optimistic report from the U.S. Federal Reserve, a new study suggests.

Economists at The Ohio State University found that the mean net worth of American households in mid-2013 was still about 14 percent below the pre-recession peak in 2006. Their analysis suggested that middle-aged people took the biggest hit.

In a report last June, the Federal Reserve said that net worth of Americans – which includes the value of homes, stocks and other assets minus debts ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

With the right prompts, AI chatbots analyze big data accurately

Leisure-time physical activity and cancer mortality among cancer survivors

Chronic kidney disease severity and risk of cognitive impairment

Research highlights from the first Multidisciplinary Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Symposium

New guidelines from NCCN detail fundamental differences in cancer in children compared to adults

Four NYU faculty win Sloan Foundation research fellowships

Personal perception of body movement changes when using robotic prosthetics

[Press-News.org] Fruit fly's pruning protein could be key to treating brain injurySingle protein controls Drosophila nervous system development and survival