(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — On the other side of the cocaine high is the cocaine crash, and understanding how one follows the other can provide insight into the physiological effects of drug abuse. For decades, brain research has focused on the pleasurable effects of cocaine largely by studying the dopamine pathway. But this approach has left many questions unanswered.

So the Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory (BPL) at UC Santa Barbara decided to take a different approach by examining the motivational systems that induce an animal to seek cocaine in the first place. Their findings appear in today's issue of The Journal of Neuroscience.

"We weren't looking at pleasure; we were looking at the animal's desire to seek that pleasure, which we believe is they key to understanding drug abuse," said Aaron Ettenberg, a professor in UCSB's Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences who established the BPL in 1982. The lab has been particularly active in the development and use of novel behavioral assays that provide a unique approach to the study of drug-behavior interactions.

The findings suggest that the same neural mechanism responsible for the negative effects of cocaine likely contribute to the animal's decision to ingest cocaine. "Just looking at the positive is looking at only half the picture; you have to understand the negative side as well," said Ettenberg.

"It's not just the positive, rewarding effects of cocaine that drive this desire to seek the drug" he said. "It's the net reward, which takes into account the negative consequences in addition to the positive. Together the two determine the net positive output that will lead to the motivated behavior."

Ettenberg's team chose to study norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline), because cocaine is known to act upon this primary neurotransmitter. The researchers chose two places in the brain — the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) — because both have been implicated in the aversive effects of such emotional processes as fear conditioning and general anxiety. Norepinephrine is a major transmitter in these two brain systems and plays a part in regulating anxiety.

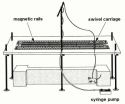

Lead author Jennifer Wenzel chose a unique way to reproduce the results of previous work she had done at UCSB, where she earned her Ph.D. in 2013. An earlier study used reversible lesions in the BNST and CeA to block the function in these two areas and then examined their effects in a unique animal model of cocaine self-administration.

For that study, the investigators trained rats to run down a custom-built 6-foot-long runway for a daily dose of cocaine. Each day they responded more quickly than the last, demonstrating an increasing motivation to get cocaine.

"Over several trials, however, rats developed an ambivalence about entering the goal box: they rapidly approached the goal but then turned and retreated back toward the start box," Wenzel explained. "These retreats can happen several times before rats finally enter the goal box and receive an injection of cocaine."

This retreat behavior became more and more prevalent as testing continued and reflects the animals' learning that negative effects (the crash) follow the positive effects (euphoria) of cocaine. Blocking the function of the BNST or the CeA resulted in a dramatic decrease in retreat behavior because the negative effects of the drug were blocked.

In the newly published paper, the researchers used drugs that selectively block the action of the neurotransmitter, noradrenaline, in the BNST and CeA rather than the entire function. The results were similar to those in the earlier study. "If you put norepinephrine antagonists directly into the BNST or the CeA, you can prevent or dramatically attenuate the negative effects of cocaine, leaving the positive effects intact," Ettenberg explained. "So the animals show fewer retreats in the runway."

The study looked at acute cocaine use with only one injection a day, which is not considered a model of addiction. So the natural extension of this paper's line of inquiry is how the positive and negative systems associated with cocaine use change when animals are exposed to multiple doses in any given day (i.e. addiction). Subsequent studies have demonstrated that as the animals become addicted to the drug, the positive consequences get reduced and negative effects get exaggerated so the net experience is less positive. To overcome the decreased positive effects, users increase the dose, which creates a behavioral spiral.

"We need to more fully understand the underlying neuronal mechanisms altered by cocaine before we can treat people," Ettenberg said. "Once we understand how the brain systems producing the positive/euphoric and negative/anxiety effects of the drug interact, we might be able to produce treatments that address the balance between these two opposing actions, both of which serve as strong driving forces. We therefore need to understand both of these systems in order to come up with a rational treatment down the line."

INFORMATION: END

UCSB study explores cocaine and the pleasure principle

Researchers use animal models to demonstrate that the net result of cocaine use is a balance of both positive and negative effects

2014-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

First-ever 3D image created of the structure beneath Sierra Negra volcano

2014-03-05

The Galápagos Islands are home to some of the most active volcanoes in the world, with more than 50 eruptions in the last 200 years. Yet until recently, scientists knew far more about the history of finches, tortoises, and iguanas than of the volcanoes on which these unusual fauna had evolved.

Now research out of the University of Rochester is providing a better picture of the subterranean plumbing system that feeds the Galápagos volcanoes, as well as a major difference with another Pacific Island chain—the Hawaiian Islands. The findings have been published in the Journal ...

Brain circuits multitask to detect, discriminate the outside world

2014-03-05

Imagine driving on a dark road. In the distance you see a single light. As the light approaches it splits into two headlights. That's a car, not a motorcycle, your brain tells you.

A new study found that neural circuits in the brain rapidly multitask between detecting and discriminating sensory input, such as headlights in the distance. That's different from how electronic circuits work, where one circuit performs a very specific task. The brain, the study found, is wired in way that allows a single pathway to perform multiple tasks.

"We showed that circuits in the ...

Similarity breeds proximity in memory, NYU researchers find

2014-03-05

Researchers at New York University have identified the nature of brain activity that allows us to bridge time in our memories. Their findings, which appear in the latest issue of the journal Neuron, offer new insights into the temporal nature of how we store our recollections and may offer a pathway for addressing memory-related afflictions.

"Our memories are known to be 'altered' versions of reality, and how time is altered has not been well understood," said Lila Davachi, an associate professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and Center for Neural Science and the ...

Are bilingual kids more open-minded?

2014-03-05

This news release is available in French. Montreal, March 5, 2014 — There are clear benefits to raising a bilingual child. But could there be some things learning a second language doesn't produce, such as a more open-minded youngster?

New research from Concordia University shows that, like monolingual children, bilingual children prefer to interact with those who speak their mother tongue with a native accent rather than with peers with a foreign accent.

The study, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology and co-authored by psychology professors Krista ...

Save money and the planet: Turn your old milk jugs into 3D printer filament

2014-03-05

Making your own stuff with a 3D printer is vastly cheaper than what you'd pay for manufactured goods, even factoring in the cost of buying the plastic filament.

Yet, you can drive the cost down even more by making your own filament from old milk jugs. And, while you are patting yourself on the back for saving 99 cents on the dollar, there's a bonus: you can feel warm and fuzzy about preserving the environment.

A study led by Joshua Pearce of Michigan Technological University has shown that making your own plastic 3D printer filament from milk jugs uses less energy—often ...

Seeking quantum-ness: D-Wave chip passes rigorous tests

2014-03-05

With cutting-edge technology, sometimes the first step scientists face is just making sure it actually works as intended.

The USC Viterbi School of Engineering is home to the USC-Lockheed Martin Quantum Computing Center (QCC), a super-cooled, magnetically shielded facility specially built to house the first commercially available quantum computing processors – devices so advanced that there are only two in use outside the Canadian lab where they were built: The first one went to USC and Lockheed Martin, and the second to NASA and Google.

Since USC's facility opened ...

Calcium and vitamin D improve cholesterol in postmenopausal women

2014-03-05

CLEVELAND, Ohio (March 5, 2014)—Calcium and vitamin D supplements after menopause can improve women's cholesterol profiles. And much of that effect is tied to raising vitamin D levels, finds a new study from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) just published online in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS).

Whether calcium or vitamin D can indeed improve cholesterol levels has been debated. And studies of women taking the combination could not separate the effects of calcium from those of vitamin D on cholesterol. But this study, led by NAMS ...

Blocking immune system protein in mice prevents fetal brain injury, but not preterm birth

2014-03-05

An inflammatory protein that triggers a pregnant mouse's immune response to an infection or other disease appears to cause brain injury in her fetus, but not the premature birth that was long believed to be linked with such neurologic damage in both rodents and humans, new Johns Hopkins-led research suggests.

The researchers, reporting online March 5 in the American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, also say they found that an anti-inflammatory drug that is FDA-approved for rheumatoid arthritis and is believed to be safe for humans to take during pregnancy halted the ...

New program for students with autism offers hope after high school

2014-03-05

An innovative program from UNC's Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute (FPG) and 6 partner universities is preparing students with autism for life after high school.

"Public high schools may be one of the last best hopes for adolescents with autism—and for their families," said FPG director Samuel L. Odom. "Many of these students will face unemployment and few social ties after school ends."

According to Odom, teachers and other professionals in the schools work hard to achieve beneficial results for students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). But positive ...

Darwin: It's not all sexual (selection)

2014-03-05

Since the days of Darwin, scientists have considered bird song to be an exclusively male trait, resulting from sexual selection. Now a team of researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), the University of Melbourne in Australia, Leiden University in the Netherlands and The Australian National University says that's not the whole story.

The team used information from several sources, including the Handbook of the Birds of the World. Their survey included birds from all over the globe, but focused on early-diverging Australasian lineages, which ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] UCSB study explores cocaine and the pleasure principleResearchers use animal models to demonstrate that the net result of cocaine use is a balance of both positive and negative effects