(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

NASA Goddard's Aki Roberge explains how observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile tell us about poison gas, comet swarms and a hypothetical planet around Beta Pictoris....

Click here for more information.

An international team of astronomers exploring the disk of gas and dust around a nearby star have uncovered a compact cloud of poisonous gas formed by ongoing rapid-fire collisions among a swarm of icy, comet-like bodies. The researchers suggest the comet swarm is either the remnant of a crash between two icy worlds the size of Mars or frozen debris trapped and concentrated by the gravity of an as-yet-unseen planet.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the researchers mapped millimeter-wavelength light from dust and carbon monoxide (CO) molecules in a disk surrounding the bright star Beta Pictoris. Located about 63 light-years away and only 20 million years old, the star hosts one of the closest, brightest and youngest debris disks known, making it an ideal laboratory for studying the early development of planetary systems.

"Although toxic to us, carbon monoxide is one of many gases found in comets and other icy bodies," said team member Aki Roberge, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "In the rough-and-tumble environment around a young star, these objects frequently collide and generate fragments that release dust, icy grains and stored gases."

The ALMA images reveal a vast belt of carbon monoxide located at the fringes of the Beta Pictoris system. Much of the gas is concentrated in a single clump located about 8 billion miles (13 billion kilometers) from the star, or nearly three times the distance between the planet Neptune and the sun. The total amount of CO observed, the scientists say, exceeds 200 million billion tons, equivalent to about one-sixth the mass of Earth's oceans.

The presence of all this gas is a clue that something interesting is going on because ultraviolet starlight breaks up CO molecules in about 100 years, much faster than the main cloud can complete a single orbit around the star. "So unless we are observing Beta Pictoris at a very unusual time, then the carbon monoxide we observed must be continuously replenished," said Bill Dent, a researcher at the Joint ALMA Office in Santiago, Chile, and the lead author of a paper published by Science Express on March 6.

Dent and his team calculate that to offset the destruction of CO molecules around Beta Pictoris, a large comet must be completely destroyed every five minutes. Only an unusually massive and compact swarm of comets could support such an astonishingly high collision rate.

Because we view the disk nearly edge-on, the ALMA data cannot determine whether the carbon monoxide belt has a single concentration of gas or two on opposite sides of the star. Further studies of the gas cloud's orbital motion will clarify the situation, but current evidence favors a two-clump scenario.

In our own solar system, Jupiter's gravity has trapped thousands of asteroids in two groups, one leading and one following the planet as it travels around the sun. A giant planet located in the outer reaches of the Beta Pictoris system likewise could corral comets into a pair of tight, massive swarms.

"Detailed dynamical studies are now under way, but at the moment we think this shepherding planet would be around Saturn's mass and positioned near the inner edge of the CO belt," said coauthor Mark Wyatt, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge in England.

Astronomers have directly imaged one giant planet, Beta Pictoris b, with a mass several times greater than Jupiter, orbiting much closer to the star. While it would be unusual for a giant planet to form up to 10 times farther away, as required to shepherd the massive comet clouds, the hypothetical planet could have formed near the star and migrated outward as the young disk underwent changes.

"We think the Beta Pictoris comet swarms formed when the hypothetical planet migrated outward, sweeping icy bodies into resonant orbits," explained Wyatt. When the orbital periods of the comets matched the planet's in some simple ratio – say, two orbits for every three of the planet – the comets received a nudge from the planet at the same location every orbit. Like regular pushes on a child's swing, these accelerations amplify over time and work to confine the comets in a small region.

If, however, the gas actually turns out to reside in a single clump, the researchers suggest an alternative scenario. A crash between two Mars-sized icy planets about half a million years ago would account for the comet swarm, with frequent ongoing collisions among the fragments gradually releasing carbon monoxide gas.

Either way, Beta Pictoris clearly has a fascinating story to tell, and ALMA's keen vision will help astronomers delve ever deeper into the tale.

INFORMATION: END

Nearby star's icy debris suggests 'shepherd' planet

2014-03-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study provides new information about the sea turtle 'lost years'

2014-03-06

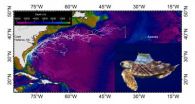

MIAMI – A new study satellite tracked 17 young loggerhead turtles in the Atlantic Ocean to better understand sea turtle nursery grounds and early habitat use during the 'lost years.' The study, conducted by a collaborative research team, including scientists from the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, was the first long-term satellite tracking study of young turtles at sea.

"This is the first time we were able to show the maiden voyage of young turtles after they left the beach," said Rosenstiel School scientist Jiangang Luo ...

$4M grant to improve asthma care for So Cal Latino youth

2014-03-06

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (March 6, 2014)—A team led by researchers at San Diego State University has been awarded $4 million to enhance asthma education and treatment strategies in California's Imperial Valley, where children are twice as likely as the national average to suffer from asthma.

The grant will allow researchers to better understand the specific asthma needs of Imperial Valley's largely Latino/Latina population, as well as develop more effective approaches to treatment for families, communities, and physicians.

Approximately 4.5 million African-Americans and 3.6 ...

Fertilizer in small doses yields higher returns for less money

2014-03-06

URBANA, Ill. - Crop yields in the fragile semi-arid areas of Zimbabwe have been declining over time due to a decline in soil fertility resulting from mono-cropping, lack of fertilizer, and other factors. In collaboration with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), University of Illinois researchers evaluated the use of a precision farming technique called "microdosing," its effect on food security, and its ability to improve yield at a low cost to farmers.

"Microdosing involves applying a small, affordable amount of fertilizer ...

Story Tips from the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, March 2014

2014-03-06

MATERIALS – Lighter, stronger engines . . .

Engines could become lighter and more efficient because of a research project that combines the talents and resources of the Chrysler Group, Nemak S.A. of Mexico and Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The goal of the four-year $5.5 million cooperative research and development agreement is to develop an advanced cast aluminum alloy for next-generation higher efficiency engines. In addition to being lighter, the new alloy for cylinder heads would be stronger and capable of sustaining the higher temperatures and pressures of engines ...

Preschoolers can outsmart college students at figuring out gizmos

2014-03-06

Preschoolers can be smarter than college students at figuring out how unusual toys and gadgets work because they're more flexible and less biased than adults in their ideas about cause and effect, according to new research from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Edinburgh.

The findings suggest that technology and innovation can benefit from the exploratory learning and probabilistic reasoning skills that come naturally to young children, many of whom are learning to use smartphones even before they can tie their shoelaces. The findings also ...

Kawasaki disease and pregnant women

2014-03-06

In the first study of its type, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have looked at the health threat to pregnant women with a history of Kawasaki disease (KD), concluding that the risks are low with informed management and care.

The findings are published in the March 6, 2014 online edition of the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

KD is a childhood condition affecting the coronary arteries. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children. First recognized in Japan following World War II, KD diagnoses ...

Early detection helps manage a chronic graft-vs.-host disease complication

2014-03-06

SEATTLE – A simple questionnaire that rates breathing difficulties on a scale of 0 to 3 predicts survival in chronic graft-vs.-host disease, according to a study published in the March issue of Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

And although a poor score means a higher risk of death, asking a simple question that can spot lung involvement early means that patients can begin treatments to reduce or manage symptoms, said senior author Stephanie Lee, M.D., M.P.H., research director of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's Long-Term Follow-Up Program, member ...

Crashing comets explain surprise gas clump around young star

2014-03-06

Beta Pictoris, a nearby star easily visible to the naked eye in the southern sky, is already hailed as the archetypal young planetary system. It is known to harbour a planet that orbits some 1.2 billion kilometres from the star, and it was one of the first stars found to be surrounded by a large disc of dusty debris [1].

New observations from ALMA now show that the disc is permeated by carbon monoxide gas.

Paradoxically the presence of carbon monoxide, which is so harmful to humans on Earth, could indicate that the Beta Pictoris planetary system may eventually become ...

ALMA sees icy wreckage in nearby solar system

2014-03-06

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope have discovered the splattered remains of comets colliding together around a nearby star; the researchers believe they are witnessing the total destruction of one of these icy bodies once every five minutes.

The "smoking gun" implicating this frosty demolition is the detection of a surprisingly compact region of carbon monoxide (CO) gas swirling around the young, nearby star Beta Pictoris.

"Molecules of CO can survive around a star for only a brief time, about 100 years, before being ...

Galactic gas caused by colliding comets suggests mystery 'shepherd' exoplanet

2014-03-06

Astronomers exploring the disk of debris around the young star Beta Pictoris have discovered a compact cloud of carbon monoxide located about 8 billion miles (13 billion kilometers) from the star. This concentration of poisonous gas – usually destroyed by starlight – is being constantly replenished by ongoing rapid-fire collisions among a swarm of icy, comet-like bodies.

In fact, to offset the destruction of carbon monoxide (CO) molecules around the star, a large comet must be getting completely destroyed every five minutes, say researchers.

They suggest the comet swarm ...