(Press-News.org) STANFORD, Calif. — Some sour news for lactose-intolerant people who hoped that raw milk might prove easier to stomach than pasteurized milk: A pilot study from the Stanford University School of Medicine shows little difference in digestibility between the two.

The study was small — it involved 16 participants — but the lead investigator said the results were highly consistent among all the participants and deflate some of the claims surrounding raw, or unpasteurized, milk.

"It's not that there was a trend toward a benefit from raw milk and our study wasn't big enough to capture it; it's that there was no hint of any benefit," said nutrition expert Christopher Gardner, PhD, professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center and senior author of the study, which will be published March 10 in the Annals of Family Medicine.

Although relatively few people drink raw milk — it's thought to comprise less than 1 percent of milk consumed nationwide — Gardner said he believes in making sure that the claims regarding foods or supplements are based on sound science. "When claims about 'all-natural' foods are merely anecdotal, it works against the food movement and undermines nutrition science," he said. "Let's get to the part that's real and do away with myths and anecdotes."

For people who are lactose-intolerant, eating dairy products can be painful. Their bodies lack enough lactase, which is the enzyme that breaks down lactose, the sugar in milk and milk products. This digestion difficulty can cause stomach cramps and diarrhea, among other symptoms. But many people who report discomfort after consuming dairy products haven't been formally tested for the condition, making it difficult to know how many meet the clinical standards for lactose-intolerance, Gardner said.

Although many strategies for coping with the condition exist — taking lactase enzyme tablets, choosing lactose-free foods — none of them fully eliminates the problem. In recent years, proponents of raw milk have cited examples of lactose-intolerant people who were able to drink raw milk without consequences. Some raw-milk producers claim that because the product isn't pasteurized, it contains "good" bacteria that can increase lactose absorption.

"When I heard that claim it didn't make sense to me because, regardless of the bacteria, raw milk and pasteurized milk have the same amount of lactose in them," Gardner said. "But I liked the idea of taking this on since it seemed like a relatively straightforward and answerable question because the symptoms of lactose-intolerance are immediate. If drinking milk makes you uncomfortable, you will know within two hours. You either have cramps and diarrhea or you don't."

For the pilot study, Gardner's team recruited 16 participants who were tested to confirm their lactose-intolerant status. The test measures the amount of hydrogen in a person's breath after drinking a beverage that contains lactose. Higher levels of hydrogen, as set by a National Institutes of Health panel, are present when undigested lactose ferments in the colon, which occurs for "malabsorbers." (Of the 63 potential study participants who reported having mild to moderate symptoms and who were screened, only 43 percent actually met the malabsorption standard, Gardner noted.)

The trial had a "crossover" design, meaning the participants each consumed three different types of milk during the course of the study: pasteurized milk, raw milk and soy milk, which doesn't have lactose and served as a control. "The crossover design is really compelling because it means each participant can evaluate their symptoms in the same way as they drink the different kinds of milk," Gardner said.

The participants were randomly assigned the order in which to consume the different milks, which were provided in unlabeled containers. Additionally, small amounts of sugar-free vanilla syrup were added to all three milks to make it more difficult for the participants to know which one they were drinking.

For eight days, the participants consumed one type of milk, with the quantities increasing between days two (4 ounces of milk) and seven (24 ounces). On the first and eighth days, they consumed 16 ounces of milk and underwent breath tests days to gauge the amount of hydrogen they were exhaling. They had the option of consuming none or a smaller portion of the milk on any of the days if their symptoms became too severe. After a one-week clearing-out period in which they consumed no milk products, the participants repeated the process for the two other types of milk.

The participants were also given a log in which to record the severity of four symptoms — gas, diarrhea, audible bowel sounds and abdominal cramping — on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the most severe.

When the team compared the hydrogen breath test results, they found little difference between the consumption of raw milk and pasteurized milk. In fact, the hydrogen levels on the first day of the eight-day period were higher for raw milk than for pasteurized milk, but those differences were no longer present on the eighth day, Gardner said.

The participants also didn't notice a difference in the severity of their symptoms when drinking raw versus pasteurized milk. Unsurprisingly, they reported the most discomfort on the seventh day of two portions of the trial when they consumed the largest amount — 24 ounces in one sitting — of either raw or pasteurized milk. In rating their symptoms on the 0-to-10 scale, the participants put their discomfort levels at an average of 4 when drinking the most of both types of dairy milk.

In the final tally, Gardner noted that 13 of the 16 participants were willing to drink the full 24 ounces of both raw milk and pasteurized milk. "I was stunned that so many of them tolerated that much milk because these were people who are clinically lactose-intolerant," he said.

Irene Gabashvili of Sunnyvale, Calif., said she happily volunteered for the trial. She remembers drinking raw milk as a young girl at her grandmother's farm, but said that in her 30s she began developing discomfort when she drank milk.

"By participating in this trial, I realized that milk is everywhere — it's in salad dressing, it's even in bread," Gabashvili said. She used to purchase lactose-free products, but has since stopped because she found she liked soy milk after drinking it during the trial and she also discovered she could tolerate small amounts of pasteurized milk.

Although the number of participants was small, Gardner said the pilot study is a solid first step and provides meaningful evidence that could be pursued in a larger trial. He said future studies should note that the participants were willing to tolerate the discomforts of drinking milk for eight days, which he believed was long enough to determine whether their digestive systems adapted to the additional bacteria in raw milk.

"We brought in focus groups of lactose-intolerant people to get feedback before we started the study, and they said they would be willing to put up with the symptoms for about a week, so I doubt if other researchers could find people who would be willing to do it for a year, but they might be able to get them to try it for two weeks," Gardner said.

INFORMATION:

The lead author of the study is former undergraduate student Sarah Mummah. Other co-authors are study coordinator Beibei Oelrich, MD, PhD; research nurse Jessica Hope; and former undergraduate student Quyen Vu.

The study was funded by the Weston A. Price Foundation and by Stanford's Program in Human Biology.

Information about Stanford's Department of Medicine, in which the work was conducted, is available at http://medicine.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Print media contact: Susan Ipaktchian at (650) 725-5375 (susani@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: Margarita Gallardo at (650) 723-7897 (mjgallardo@stanford.edu)

Claim that raw milk reduces lactose intolerance doesn't pass smell test, study finds

2014-03-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Small biomass power plants could help rural economies, stabilize national power grid, MU study finds

2014-03-10

COLUMBIA, Mo. – As energy costs rise, more Americans are turning to bioenergy to provide power to their homes and workplaces. Bioenergy is renewable energy made from organic sources, such as biomass. Technology has advanced enough that biomass power plants small enough to fit on a farm can be built at relatively low costs. Now, University of Missouri researchers have found that creating a bioenergy grid with these small plants could benefit people in rural areas of the country as well as provide relief to an overworked national power grid.

"Transporting power through ...

UV light aids cancer cells that creep along the outside of blood vessels

2014-03-10

A new study by UCLA scientists and colleagues adds further proof to earlier findings by Dr. Claire Lugassy and Dr. Raymond Barnhill of UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center that deadly melanoma cells can spread through the body by creeping like tiny spiders along the outside of blood vessels without ever entering the bloodstream.

In addition, the new research, published March 6 in the journal Nature, demonstrates that this process is accelerated when the skin cancer cells are exposed to ultraviolet light. The husband-and-wife team of Barnhill and Lugassy collaborated ...

Natural selection has altered the appearance of Europeans over the past 5,000 years

2014-03-10

There has been much research into the factors that have influenced the human genome since the end of the last Ice Age. Anthropologists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and geneticists at University College London (UCL), working in collaboration with archaeologists from Berlin and Kiev, have analyzed ancient DNA from skeletons and found that selection has had a significant effect on the human genome even in the past 5,000 years, resulting in sustained changes to the appearance of people. The results of this current research project have been published this week ...

JCI online ahead of print table of contents for March 10, 2014

2014-03-10

Identification of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody in a lupus patient

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs) recognize conserved epitopes, representing a promising strategy for targeting rapidly mutating viruses. BnAbs display a unique set of characteristics that suggest their development may be limited by immune tolerance. Interestingly, the HIV-1 infection frequency is disproportionately low among patients with the autoimmune disease lupus. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Mattia Bonsignori and colleagues at Duke University identified an ...

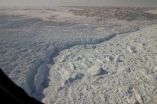

NASA data shed new light on changing Greenland ice

2014-03-10

Research using NASA data is giving new insight into one of the processes causing Greenland's ice sheet to lose mass. A team of scientists used satellite observations and ice thickness measurements gathered by NASA's Operation IceBridge to calculate the rate at which ice flows through Greenland's glaciers into the ocean. The findings of this research give a clearer picture of how glacier flow affects the Greenland Ice Sheet and shows that this dynamic process is dominated by a small number of glaciers.

Over the past few years, Operation IceBridge measured the thickness ...

Shade will be a precious resource to lizards in a warming world

2014-03-10

Climate change may even test lizards' famous ability to tolerate and escape the heat -- making habitat protection increasingly vital -- according to a new study by UBC and international biodiversity experts.

The study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looks at the heat and cold tolerance of 296 species of reptiles, insects and amphibians, known as ectotherms. The researchers discovered that regardless of latitude or elevation, cold-blooded animals across the world have similar heat tolerance limits. However, species in the tropics ...

A tale of 2 data sets: New DNA analysis strategy helps researchers cut through the dirt

2014-03-10

For soil microbiology, it is the best of times. While no one has undertaken an accurate census, a spoonful of soil holds hundreds of billions of microbial cells, encompassing thousands of species. "It's one of the most diverse microbial habitats on Earth, yet we know surprisingly little about the identities and functions of the microbes inhabiting soil," said Jim Tiedje, Distinguished Professor at the Center for Microbial Ecology at Michigan State University. Tiedje, along with MSU colleagues and collaborators from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE ...

Mecasermin (rh-IGF-1) treatment for Rett Syndrome is safe and well-tolerated

2014-03-10

(Cincinnati, OH) – The results from Boston Children's Hospital's Phase 1 human clinical trial in Rett syndrome came out today. A team of investigators successfully completed a Phase 1 clinical trial using mecasermin [recombinant human insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)], showing proof-of-principle that treatments like IGF-1 which are based on the neurobiology of Rett syndrome, are possible. The study deemed that IGF-1 is safe and well tolerated in girls diagnosed with Rett syndrome, and the data also suggests that certain breathing and behavioral symptoms associated ...

National study reveals urban lawn care habits

2014-03-10

(Millbrook, NY) What do people living in Boston, Baltimore, Miami, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Phoenix, and Los Angeles have in common? From coast to coast, prairie to desert – residential lawns reign.

But, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, beneath this sea of green lie unexpected differences in fertilization and irrigation practices. Understanding urban lawn care is vital to sustainability planning, more than 80% of Americans live in cities and their suburbs, and these numbers continue to grow.

The study was undertaken to ...

Lower IQ in teen years increases risk of early-onset dementia

2014-03-10

Men who at the age of 18 years have poorer cardiovascular fitness and/or a lower IQ more often suffer from dementia before the age of 60. This is shown in a recent study encompassing more than one million Swedish men.

In several extensive studies, researchers at the Sahlgrenska Academy of Gothenburg University have previously analyzed Swedish men's conscription results and were able to show a correlation between cardiovascular fitness as a teenager and health problems in later life.

Increased risk for early-onset dementia

In their latest study, based on data from 1.1 ...