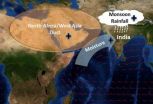

(Press-News.org) RICHLAND, Wash. -- A new analysis of satellite data reveals a link between dust in North Africa and West Asia and stronger monsoons in India. The study shows that dust in the air absorbs sunlight west of India, warming the air and strengthening the winds carrying moisture eastward. This results in more monsoon rainfall about a week later in India. The results explain one way that dust can affect the climate, filling in previously unknown details about the Earth system.

The study also shows that natural airborne particles can influence rainfall in unexpected ways, with changes in one location rapidly affecting weather thousands of miles away. The researchers analyzed satellite data and performed computer modeling of the region to tease out the role of dust on the Indian monsoon, they report March 16 in Nature Geoscience.

India relies heavily on its summer monsoon rains. "The difference between a monsoon flood year or a dry year is about 10 percent of the average summer rainfall in central India. Variations driven by dust may be strong enough to explain some of that year-to-year variation," said climate scientist Phil Rasch of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Rasch, V. Vinoj of the Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, India, and their coauthors wanted to explore a correlation that appeared in satellite records: higher amounts of small particles called aerosols over North Africa, West Asia, and the Arabian Sea seemed to be connected to stronger rainfall over India around the same time. The team wanted to see if they could verify this and determine how those particles might affect rainfall.

To explore the connection, the team used a computer model called CAM5 and focused on the area. The model included manmade aerosols from pollution, and natural sea salt and dust aerosols. First, the team ran the model and noted a similar connection: more aerosols in the west meant more rainfall in the east. Then they systematically turned off the contribution of each aerosol type and looked to see if the connection remained.

Dust turned out to be the necessary ingredient. The condition that re-created stronger rainfall in India was the rise of dust in North Africa and the Arabian peninsula.

To see how quickly dust worked, they ran short computer simulations with and without dust emissions. Without dust emissions, the atmospheric dust disappeared within a week compared to the simulation with dust emissions and rainfall declined in central India as well. This indicated the effect happens over a short period of time.

But there was one more mystery, how did dust do this to rainfall? To explore possibilities, the team zoomed in on the regional conditions such as air temperature and water transport through the air.

Their likeliest possibility focused on the fact that dust can absorb sunlight that would normally reach the surface, warming the air instead. This warmer dust-laden air draws moist air from the tropics northward, and strengthens the prevailing winds that move moisture from the Arabian Sea into India, where it falls as rain.

Although dust plays a role in strengthening monsoons, this natural phenomenon does not overpower many other processes that also influence monsoons, said Rasch. Other extremely important factors include the effect of temperature differences between land and ocean, land use changes, global warming, and local effects of pollution aerosols around India that can heat and cool the air, and also affect clouds, he said.

"The strength of monsoons have been declining for the last 50 years," he said. "The dust effect is unlikely to explain the systematic decline, but it may contribute."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science and PNNL.

Reference: V. Vinoj, Philip J. Rasch, Hailong Wang, Jin-Ho Yoon, Po-Lun Ma, Kiranmayi Landu and Balwinder Singh. Short-term modulation of Indian summer monsoon rainfall by West Asian dust, Nature Geoscience March 16, 2014, doi:10.1038/NGEO2107. (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2107)

The Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Interdisciplinary teams at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory address many of America's most pressing issues in energy, the environment and national security through advances in basic and applied science. PNNL employs 4,500 staff, has an annual budget of nearly $1 billion, and has been managed for the U.S. Department of Energy by Ohio-based Battelle since the laboratory's inception in 1965. For more, visit the PNNL's News Center, or follow PNNL on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

The rush to rain

Dust kicked up in Asia strengthens Indian monsoon within a week

2014-03-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers: Northeast Greenland ice loss accelerating

2014-03-16

COLUMBUS, Ohio—An international team of scientists has discovered that the last remaining stable portion of the Greenland ice sheet is stable no more.

The finding, which will likely boost estimates of expected global sea level rise in the future, appears in the March 16 issue of the journal Nature Climate Change [DOI:10.1038/NCLIMATE2161].

The new result focuses on ice loss due to a major retreat of an outlet glacier connected to a long "river" of ice - known as an ice stream - that drains ice from the interior of the ice sheet. The Zachariae ice stream retreated about ...

Mercury's contraction much greater than thought

2014-03-16

Washington, D.C.—New global imaging and topographic data from MESSENGER* show that the innermost planet has contracted far more than previous estimates. The results are based on a global study of more than 5,900 geological landforms, such as curving cliff-like scarps and wrinkle ridges, that have resulted from the planet's contraction as Mercury cooled. The findings, published online March 16, 2014, in Nature Geoscience, are key to understanding the planet's thermal, tectonic, and volcanic history, and the structure of its unusually large metallic core.

Unlike Earth, ...

Thermal vision: Graphene light detector first to span infrared spectrum

2014-03-16

ANN ARBOR—The first room-temperature light detector that can sense the full infrared spectrum has the potential to put heat vision technology into a contact lens.

Unlike comparable mid- and far-infrared detectors currently on the market, the detector developed by University of Michigan engineering researchers doesn't need bulky cooling equipment to work.

"We can make the entire design super-thin," said Zhaohui Zhong, assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science. "It can be stacked on a contact lens or integrated with a cell phone."

Infrared ...

Southern Ocean iron cycle gives new insight into climate change

2014-03-16

An international team of researchers analysed the available data taken from all previous studies of the Southern Ocean, together with satellite images taken of the area, to quantify the amount of iron supplied to the surface waters of the Southern Ocean.

They found that deep winter mixing, a seasonal process which carries colder and deeper, nutrient-rich water to the surface, plays the most important role in transporting iron to the surface. The iron is then able to stimulate phytoplankton growth which supports the ocean's carbon cycle and the aquatic food chain

They ...

Regional warming triggers sustained mass loss in Northeast Greenland ice sheet

2014-03-16

Northeast Greenland, where the glacier is found, is of particular interest as numerical model predictions have suggested there is no significant mass loss for this sector, leading to a probable underestimation of future global sea-level rise from the region.

An international team of scientists, including Professor Jonathan Bamber from the University of Bristol, studied the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream which extends more than 600 km into the interior of the ice sheet: much further than any other in Greenland.

Professor Bamber said: "The Greenland ice sheet has contributed ...

Cancer therapy may be too targeted

2014-03-16

Researchers have identified two novel cancer genes that are associated with the development of a rare, highly aggressive, cancer of blood vessels. These genes may now act as markers for future treatments and explain why narrowly targeted therapies that are directed at just one target fail.

Angiosarcoma is a rare cancer of blood vessels. It occurs either spontaneously or can appear after radiotherapy treatment. Although quite rare, with approximately 100 people diagnosed with the cancer in the UK each year, the survival outcomes for the cancer are poorer than many other ...

Mercury contracted more than prior estimates, evidence shows

2014-03-16

New evidence gathered by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft at Mercury indicates the planet closest to the sun has shrunk up to 7 kilometers in radius over the past 4 billion years, much more than earlier estimates.

The new finding, published in the journal Nature Geoscience Sunday, March 16, solves an apparent enigma about Mercury's evolution.

Older images of surface features indicated that, despite cooling over its lifetime, the rocky planet had barely shrunk at all. But modeling of the planet's formation and aging could not explain that finding.

Now, Paul K. Byrne and ...

Newly identified small-RNA pathway defends genome against the enemy within

2014-03-16

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – Reproductive cells, such as an egg and sperm, join to form stem cells that can mature into any tissue type. But how do reproductive cells arise? We humans are born with all of the reproductive cells that we will ever produce. But in plants things are very different. They first generate mature, adult cells and only later "reprogram" some of them to produce eggs and sperm.

For a plant to create reproductive cells, it must first erase a key code, a series of tags attached to DNA across the genome known as epigenetic marks. These marks distinguish ...

Novel gene-finding approach yields a new gene linked to key heart attack risk factor

2014-03-16

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Scientists have discovered a previously unrecognized gene variation that makes humans have healthier blood lipid levels and reduced risk of heart attacks -- a finding that opens the door to using this knowledge in testing or treatment of high cholesterol and other lipid disorders.

But even more significant is how they found the gene, which had been hiding in plain sight in previous hunts for genes that influence cardiovascular risk.

This region of DNA where it was found had been implicated as being important in controlling blood lipid levels in ...

Climate change will reduce crop yields sooner than we thought

2014-03-16

A study led by the University of Leeds has shown that global warming of only 2°C will be detrimental to crops in temperate and tropical regions, with reduced yields from the 2030s onwards.

Professor Andy Challinor, from the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds and lead author of the study, said: "Our research shows that crop yields will be negatively affected by climate change much earlier than expected."

"Furthermore, the impact of climate change on crops will vary both from year-to-year and from place-to-place – with the variability becoming ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] The rush to rainDust kicked up in Asia strengthens Indian monsoon within a week