(Press-News.org) We are less likely to humanize members of groups we don't belong to—except, under some circumstances, when it comes to members of the opposite political party. A study by researchers at New York University and Harvard Business School suggests that we are more prone to view members of the opposite political party as human if we view those individuals as threatening.

"It's hardly surprising that we dehumanize those who are not part of our groups," says Jay Van Bavel, an assistant professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and one of the study's co-authors. "However, what is interesting is that we may be motivated to perceive the presence of a mind among political adversaries who threaten us.

"It's possible that when we believe our political opponents are formidable we may humanize them in ways we don't with members of other out-groups."

The study appears in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

In a set of experiments with NYU undergraduates and on-line adult volunteers, participants viewed a series of faces that were morphs between human faces and inanimate faces (e.g. dolls, statues). An example of this morphing process—similar to the one used in these experiments—may be viewed here: http://bit.ly/1qDaxhX.

Participants were asked to rate how much each entity was "alive" or "had a mind" (1 [definitely has no mind/definitely not alive] to 7 [definitely has a mind/definitely alive]). To clarify the concept of "alive," participants were given the example: a snake is alive while a rock is not. To clarify the concept of "mind," participants were given the example of a human mind differing from that of an animal or robot.

In one experiment, these morphed faces were described as based on either "in-group" members or "out-group" members. In this procedure, which displayed the faces on a computer screen, subjects viewed still images of the morphed faces in random order and rated, from 1 to 7, whether each face was less (no mind/not alive) or more (mind/alive) human.

Their results showed that subjects were more likely to view "in-group" faces as having a mind than they were those faces labeled as members of an "out-group." Specifically, the "out-group" faces needed to morph into a more human form than did "in-group" faces" before they were judged by subjects as having a mind.

In a second experiment, the researchers employed real-world "in-group" and "out-group" examples. Specifically, in this procedure, the researchers labeled the human faces as either NYU students or students from Boston University (BU). University affiliation of faces was cued by an instruction screen—appearing before each facial image—that featured the university name and logo.

The researchers predicted that participants who strongly identified with NYU would be most likely to show an in-group bias. To gauge this, the NYU students responded to a series of statements (strongly agree to strongly disagree), which measured the extent to which they felt invested in, and defined themselves as members of, the NYU community.

The results showed that participants who identified more highly with NYU had higher thresholds for perceiving minds in the BU students than did those who identified less strongly with the New York institution. In other words, for subjects who identified strongly with NYU, the "out-group" (BU) faces needed to morph into a more human form than did "in-group" (NYU) faces before they were judged by these participants as having a mind.

In a final experiment, conducted online, the researchers tested the views of national sample of self-identified Democrats and Republicans in May 2012—after both parties' presidential nominees had become clear and the general election was heating up. Participants were told that they would rate images based on the faces of models from the NYU Democrats and NYU Republicans.

Participants rated the same sets of morph images from the previous studies. Before each set of images, participants saw a cue thanking members of the NYU Democrats or NYU Republicans for serving as models for the upcoming face images and featuring the logo of the political party specified. After completing their ratings, participants reported their own political party affiliation. Finally, participants were asked, "To what extent do you think Democrats (Republicans) pose a threat to Republicans (Democrats)", using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all to 7 = very much).

A portion of these results was consistent with the previous two experiments: Democrats who strongly identified with their group had a higher threshold for judging Republicans as having a mind than they did Democrats and vice versa. However, both Republicans and Democrats who viewed the out-group as threatening more readily viewed their political adversaries as having "a mind" than did those who saw no such threat.

"We often have different perceptions of the minds and mental states of in-group and out-group members," says Leor Hackel, an NYU doctoral student and the study's lead author. "However, as our findings show, these views may be altered when we take into account concerns such as perceived threat, which may increase the importance of getting inside the out-group mind. We hope these findings can offer insights into better understanding, and perhaps improving, relations between adversarial groups."

INFORMATION:

Democrats, Republicans see each other as mindless -- unless they pose a threat

2014-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research on the protein gp41 could help towards designing future vaccinations against HIV

2014-03-18

This news release is available in Spanish. Researchers from the University of Granada have discovered, for the first time, an allosteric interaction (that is, a regulation mechanism whereby enzymes can be activated or de-activated) between this protein, which forms part of the sheath of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the antibody 2F5 (FAB), a potent virus neutralizer. This important scientific breakthrough could help specialists to understand the mechanisms behind generating immune responses and help towards the design of future vaccines against the HIV ...

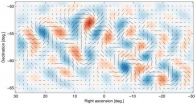

First direct evidence of cosmic inflation

2014-03-18

Almost 14 billion years ago, the universe we inhabit burst into existence in an extraordinary event that initiated the Big Bang. In the first fleeting fraction of a second, the universe expanded exponentially, stretching far beyond the view of our best telescopes. All this, of course, was just theory.

Researchers from the BICEP2 collaboration today announced the first direct evidence for this cosmic inflation. Their data also represent the first images of gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time. These waves have been described as the "first tremors of the Big Bang." ...

Immunologists present improved mass spectrometric method for proteomic analyses

2014-03-18

When it comes to analyzing cell components or body fluids or developing new medications, there is no way around mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry is a highly sensitive method of measurement that has been used for many years for the analysis of chemical and biological materials. Scientists at the Institute of Immunology of the University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have now significantly improved this analytical method that is widely employed within their field. They have also developed a software program for the integrated analysis of ...

UNH research: Positive memories of exercise spur future workouts

2014-03-18

DURHAM, N.H. – Getting motivated to exercise can be a challenge, but new research from the University of New Hampshire shows that simply remembering a positive memory about exercise may be just what it takes to get on the treadmill. This is the first study to explore how positive memories can influence future workouts.

"This study underscores the power of memory's directive influence in a new domain with practical applications: exercise behaviors. These results provide the first experimental evidence that autobiographical memory activation can be an effective tool in ...

Male, stressed, and poorly social

2014-03-18

Stress, this enemy that haunts us every day, could be undermining not only our health but also our relationships with other people, especially if we are men. In fact, stressed women apparently become more "prosocial". These are the main findings of a study carried out with the collaboration of Giorgia Silani, from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) of Trieste. The study was coordinated by the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Unit of the University of Vienna and saw the participation of the University of Freiburg.

"There's a subtle boundary between the ...

What's so bad about feeling happy?

2014-03-18

Why is being happy, positive and satisfied with life the ultimate goal of so many people, while others steer clear of such feelings? It is often because of the lingering belief that happiness causes bad things to happen, says Mohsen Joshanloo and Dan Weijers of the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. Their article, published in Springer's Journal of Happiness Studies, is the first to review the concept of aversion to happiness, and looks at why various cultures react differently to feelings of well-being and satisfaction.

"One of these cultural phenomena ...

Study fingers chickens, quail, in spread of H7N9 influenza virus

2014-03-18

Among the copious species of poultry in China, quail and chickens are the likely sources of infection of H7N9 influenza virus to humans, according to a paper published ahead of print in the Journal of Virology.

"Knowing the likely poultry species lets us target our interventions better to prevent human infections," says corresponding author David Suarez, of the United States Department of Agriculture.

The H7N9 avian influenza virus was first reported in humans in March 2013 in China. Since then over 375 human cases have been confirmed and over 100 have died. Only ...

New understanding of why chromosome errors are high in women's eggs

2014-03-18

A new study from the University of Southampton has provided scientists with a better understanding of why chromosome errors are high in women's eggs.

It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of eggs are affected by errors in how their chromosomes divide, making it the leading cause of infertility. Chromosome errors also lead to conditions such as Down Syndrome and early pregnancy loss.

By using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, the Southampton researchers examined the most important process present in all cells to prevent chromosome errors – the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint ...

Some truth to the 'potent pot myth'

2014-03-18

New research from The Netherlands shows that people who smoke high-potency cannabis end up getting higher doses of the active ingredient (THC). Although they reduce the amount they puff and inhale to compensate for the higher strength, they still take in more THC than smokers of lower potency cannabis.

For the past decade or more, the common sense idea that high strength cannabis leads to higher doses of THC and therefore poses a greater risk of unwanted effects such as dependency has been challenged and labelled the 'potent pot myth'. It has been argued that smokers ...

A new algorithm improves the efficiency of small wind turbines

2014-03-18

Small wind turbines tend to be located in areas where wind conditions are more unfavourable. "The control systems of current wind turbines are not adaptative; in other words, the algorithms lack the capacity to adapt to new situations," explained Iñigo Kortabarria, one of the researchers in the UPV/EHU'sAPERT research group. That is why "the aim of the research was to develop a new algorithm capable of adapting to new conditions or to the changes that may take place in the wind turbine," added Kortabarria. That way, the researchers have managed to increase the efficiency ...