(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, March 26, 2014 – A breast cancer therapy that blocks estrogen synthesis to activate cancer-killing genes sometimes loses its effectiveness because the cancer takes over epigenetic mechanisms, including permanent DNA modifications in the patient's tumor, once again allowing tumor growth, according to an international team headed by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI).

The finding warrants research into adding drugs that could prevent the cancer from hijacking patients' repressive gene regulatory machinery, which might allow the original therapy to work long enough to eradicate the tumor, the researchers report in their National Institutes of Health-funded study, published in the current issue of Science Translational Medicine.

"Our discovery is particularly notable as we enter the era of personalized medicine," said senior author Steffi Oesterreich, Ph.D., professor in Pitt's Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology and at UPCI, a partner with UPMC CancerCenter, and director of education at the Women's Cancer Research Center. "Resistance to hormonal therapy is a major clinical problem in the treatment of most breast cancers. Through testing of a tumor's genetic and epigenetic make-up, we may be able to identify the patients most likely to develop such resistance and, in the future, create a treatment regimen tailored to giving each patient the best chance of beating their cancer."

Epigenetic translates to "above genetic" and is an emerging field of study that looks at how environmental factors — such as infections, pollutants, stress and, in this case, long-term exposure to drugs that block estrogen synthesis — could influence a person's DNA. Epigenetic changes do not alter the structure of the DNA, but they do change the way the DNA is modified, which subsequently determines the potential of gene regulation.

By performing a genome-wide screen in breast cancer cells, Dr. Oesterreich and her colleagues identified a gene called HOXC10 as one that the cancer seems to modify to allow continued tumor growth in patients whose cancer becomes resistant to traditional therapies.

The hormone estrogen represses genes, such as HOXC10, that induce cell death and inhibit growth. About 70 percent of breast cancer tumors are positive for a protein called 'estrogen receptor alpha,' which prevents HOXC10 from killing the cancer. To overcome this, doctors put these patients on anti-estrogen therapy, including aromatase inhibitors.

Unfortunately, in some cases, the tumor uses different epigenetic mechanisms, independent of estrogen, to repress the HOXC10 gene. This allows the cancer to continue growing. When the tumor uses these mechanisms, it makes deeper modifications to the expression of the patient's DNA, permanently blocking the HOXC10 and other genes and making cancer treatment much more difficult.

"In some patients the tumors never respond to aromatase inhibitors and just keep growing. In other patients, using aromatase inhibitors to block estrogen synthesis and allow HOXC10 and other genes to destroy the cancer works in the short term," said Dr. Oesterreich. "But, eventually, we see the tumor start to gain ground again as the cancer permanently represses genes such as HOXC10. At that point, the aromatase inhibitor is no longer effective."

Dr. Oesterreich and her colleagues propose that future studies look at offering a combined therapy that, along with aromatase inhibitors, also introduces drugs that modify the epigenome to prevent or delay the cancer from repressing cancer-killing genes.

The researchers also note that more investigation is needed to fully understand all the mechanisms by which HOXC10 mediates cell proliferation and death, and the roles it may play in different types of tumors.

INFORMATION:

Additional researchers on this study are Thushangi N. Pathiraja, Ph.D., Shiming Jiang, Ph.D., Yuanxin Xi, Ph.D., Jason P. Garee, Ph.D., Dean P. Edwards, Ph.D., Martin J. Shea, Rachel Schiff, Ph.D., and Wei Lei, Ph.D., all of, or formerly of, Baylor College of Medicine; Shweta Nayak, M.D., of Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC; Adrian V. Lee, Ph.D., Jian Chen, M.S., and Nancy E. Davidson, M.D., all of UPCI; Richard J. Santen, M.D., of the University of Virginia; Frank Gannon, Ph.D., and Sara Kangaspeska, Ph.D., formerly of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory and now at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane, Australia, and at Institute for Molecular Medicine, Helsinki, Finland; Jaroslav Jelinek, M.D., Ph.D., and Jean-Pierre J. Issa, M.D., both of Temple University; Jennifer K. Richer, Ph.D., and Anthony Elias, M.D., both of the University of Colorado; and Marie McIlroy, Ph.D., and Leonie Young, Ph.D., both of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland.

This project was funded in part by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation; U.S. Department of Defense grant 5W81XWH-06-1-0713; National Institutes of Health grants P30CA125123, P30CA47904, P50CA58183, P01CA030195, R01HG007538, R01CA94118 and R01CA097213; Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation grant PG12221410; the EIF/Lee Jeans Breast Cancer Research Program; Su2C/Breast Cancer Program; Breast Cancer Research Foundation; and Pennsylvania Department of Health.

About UPCI

As the only NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in western Pennsylvania, UPCI is a recognized leader in providing innovative cancer prevention, detection, diagnosis, and treatment; biomedical research; compassionate patient care and support; and community-based outreach services. Investigators at UPCI, a partner with UPMC CancerCenter, are world-renowned for their work in clinical and basic cancer research.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Phone: 412-647-9975

E-mail: HydzikAM@upmc.edu

Contact: Jennifer Yates

Phone: 412-647-9966

E-mail: YatesJC@upmc.edu END

Some breast cancer tumors hijack patient epigenetic machinery to evade drug therapy

2014-03-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

First comprehensive atlas of human gene activity released

2014-03-26

Boston, MA — A large international consortium of researchers has produced the first comprehensive, detailed map of the way genes work across the major cells and tissues of the human body. The findings describe the complex networks that govern gene activity, and the new information could play a crucial role in identifying the genes involved with disease.

"Now, for the first time, we are able to pinpoint the regions of the genome that can be active in a disease and in normal activity, whether it's in a brain cell, the skin, in blood stem cells or in hair follicles," said ...

Brain degeneration in Huntington's disease caused by amino acid deficiency

2014-03-26

Working with genetically engineered mice, Johns Hopkins neuroscientists report they have identified what they believe is the cause of the vast disintegration of a part of the brain called the corpus striatum in rodents and people with Huntington's disease: loss of the ability to make the amino acid cysteine. They also found that disease progression slowed in mice that were fed a diet rich in cysteine, which is found in foods such as wheat germ and whey protein.

Their results suggest further investigation into cysteine supplementation as a candidate therapeutic in people ...

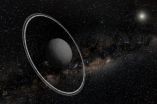

Cosmic collision creates mini-planet with rings

2014-03-26

Until now, rings of material in a disc have only been observed around giant planets like Jupiter, Uranus, Neptune and especially Saturn, which is known for its spectacular rings. Now astronomers from the Niels Bohr Institute, among others, have observed the first miniature planet with two rings of ice and pebbles. It is a smaller celestial body, called Chariklo, located two billion kilometers out in the solar system between Saturn and Uranus. The results are published in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature.

Chariklo was located in the Kuiper Belt, a collection ...

New maps for navigating the genome unveiled by scientists

2014-03-26

Scientists have built the clearest picture yet of how our genetic material is regulated in order to make the human body work.

They have mapped how a network of switches, built into our DNA, controls where and when our genes are turned on and off.

University of Edinburgh scientists played a leading role in the international project – called FANTOM5 – which has been examining how our genome holds the code for creating the fantastic diversity of cell types that make up a human.

The three year project, steered by the RIKEN Center for Life Science Technologies in Japan, ...

Keeping secrets in a world of spies and mistrust

2014-03-26

VIDEO:

This is an interview with Professor Artur Ekert, co-inventor of quantum cryptography, about what it takes to keep secrets secret.

Click here for more information.

Revelations of the extent of government surveillance have thrown a spotlight on the security – or lack thereof – of our digital communications. Even today's encrypted data is vulnerable to technological progress. What privacy is ultimately possible? In the 27 March issue of Nature, the weekly international ...

Cell-saving drugs could reduce brain damage after stroke

2014-03-26

Long-term brain damage caused by stroke could be reduced by saving cells called pericytes that control blood flow in capillaries, reports a new study led by scientists from UCL (University College London).

Until now, many scientists believed that blood flow within the brain was solely controlled by changes in the diameter of arterioles, blood vessels that branch out from arteries into smaller capillaries. The latest research reveals that the brain's blood supply is in fact chiefly controlled by the narrowing or widening of capillaries as pericytes tighten or loosen around ...

Should whole-genome sequencing become part of newborn screening?

2014-03-26

That question is likely to stir debate in coming years in many of the more-than-60 countries that provide newborn screening, as whole-genome sequencing (WGS) becomes increasingly affordable and reliable. Newborn screening programs – which involve drawing a few drops of blood from a newborn's heel – have been in place since the late 1960s, and are credited with having saved thousands of lives by identifying certain genetic, endocrine or metabolic disorders that can be treated effectively when caught early enough. Advocates of routine WGS for newborns argue that the new technology ...

Solar System's edge redefined

2014-03-26

Washington, D.C.—The Solar System has a new most-distant member, bringing its outer frontier into focus.

New work from Carnegie's Scott Sheppard and Chadwick Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory reports the discovery of a distant dwarf planet, called 2012 VP113, which was found beyond the known edge of the Solar System. This is likely one of thousands of distant objects that are thought to form the so-called inner Oort cloud. What's more, their work indicates the potential presence of an enormous planet, perhaps up to 10 times the size of Earth, not yet seen, but possibly ...

Penn Dental Medicine-NIH team reverses bone loss in immune disorder

2014-03-26

Patients with leukocyte adhesion deficiency, or LAD, suffer from frequent bacterial infections, including the severe gum disease known as periodontitis. These patients often lose their teeth early in life.

New research by University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine researchers, teaming with investigators from the National Institutes of Health, has demonstrated a method of reversing this bone loss and inflammation.

The work was led by Penn Dental Medicine's George Hajishengallis, professor in the Department of Microbiology, in collaboration with Niki Moutsopoulos ...

Researchers present comprehensive 'roadmap' of blood cells

2014-03-26

(WASHINGTON, March 26, 2014) – Research published online today in Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology, presents an unprecedented look at five unique blood cells in the human body, pinpointing the location of key genetic regulators in these cells and providing a new tool that may help scientists to identify how blood cells form and shed light on the etiology of blood diseases.

Work published today in Blood* is a subset of a much larger catalog of genetic information about nearly 1,000 human cells and tissues unveiled today from the international research ...