(Press-News.org) MANHATTAN, Kan. — Researchers have discovered that microscopic "bubbles" developed at Kansas State University are safe and effective storage lockers for harmful isotopes that emit ionizing radiation for treating tumors.

The findings can benefit patient health and advance radiation therapy used to treat cancer and other diseases, said John M. Tomich, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics who is affiliated with the university's Johnson Cancer Research Center.

Tomich conducted the study with Ekaterina Dadachova, a radiochemistry specialist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, along with researchers from his group at Kansas State University, the University of Kansas, Jikei University School of Medicine in Japan and the Institute for Transuranium Elements in Germany. They recently published their findings in the study "Branched Amphiphilic Peptide Capsules: Cellular Uptake and Retention of Encapsulated Solutes," which appears in the scientific journal Biochimica et Biophysica Acta.

The study looks at the ability of nontoxic molecules to store and deliver potentially harmful alpha emitting radioisotopes — one of the most effective forms of radiation therapy.

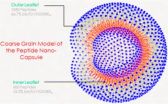

In 2012, Tomich and his research lab team combined two related sequences of amino acids to form a very small, hollow nanocapsule similar to a bubble.

"We found that the two sequences come together to form a thin membrane that assembled into little spheres, which we call capsules," Tomich said. "While other vesicles have been created from lipids, most are much less stable and break down. Ours are like stones, though. They're incredibly stable and are not destroyed by cells in the body."

The ability of the capsules to stay intact with the isotope inside and remain undetected by the body's clearance systems prompted Tomich to investigate using the capsules as unbreakable storage containers that can be used for biomedical research, particularly in radiation therapies.

"The problem with current alpha-particle radiation therapies used to treat cancer is that they lead to the release of nontargeted radioactive daughter ions into the body," Tomich said. "Radioactive atoms break down to form new atoms, called daughter ions, with the release of some form of energy or energetic particles. Alpha emitters give off an energetic particle that comes off at nearly the speed of light."

These particles are like a car careening on ice, Tomich said. They are very powerful but can only travel a short distance. On collision, the alpha particle destroys DNA and whatever vital cellular components are in its path. Similarly, the daughter ions recoil with high energy on ejection of the alpha particle — similar to how a gun recoils as it is fired. The daughter ions have enough energy to escape the targeting and containment molecules that currently are in use.

"Once freed, the daughter isotopes can end up in places you don't want them, like bone marrow, which can then lead to leukemia and new challenges," Tomich said. "We don't want any stray isotopes because they can harm the body. The trick is to get the radioactive isotopes into and contained in just diseases cells where they can work their magic."

The radioactive compound that the team works with is 225Actinium, which on decay releases four alpha particles and numerous daughter ions.

Tomich and Dadachova tested the retention and biodistribution of alpha-emitting particles trapped inside the peptide capsules in cells. The capsules readily enter cells. Once inside, they migrate to a position alongside the nucleus, where the DNA is.

Tomich and Dadachova found that as the alpha particle-emitting isotopes decayed, the recoiled daughter ion collides with the capsule walls and essentially bounces off them and remains trapped inside the capsule. This completely blocked the release of the daughter ions, which prevented uptake in certain nontarget tissues and protected the subject from harmful radiation that would have otherwise have been releases into the body.

Tomich said that more studies are needed to add target molecules to the surface of the capsules. He anticipates that this new approach will provide a safer option for treating tumors with radiation therapy by reducing the amount of radioisotope required for killing the cancer cells and reducing the side effects caused by off-target accumulation of the radioisotopes.

"These capsules are easy to make and easy to work with," Tomich said. "I think we're just scratching the surface of what we can do with them to improve human health and nanomaterials."

INFORMATION: END

Radiation able to be securely stored in nontoxic molecule, study finds

2014-04-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

From Martian rocks, a planet's watery story emerges

2014-04-02

After 18 months on Mars, the rover Curiosity has taken more than 120,000 measurements of surface rocks and soil, painting a more detailed image of how much water was once on the Red Planet. An article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN) describes the technique scientists are using to analyze the rocks and what they've found.

Celia Arnaud, a senior editor at C&EN, notes that Curiosity has traveled nearly 4 miles since it landed in 2012 and is more than halfway to its destination, Mount Sharp. But in the meantime, its onboard equipment is collecting a treasure trove of ...

Noisy brain signals: How the schizophrenic brain misinterprets the world

2014-04-02

People with schizophrenia often misinterpret what they see and experience in the world. New research provides insight into the brain mechanisms that might be responsible for this misinterpretation. The study from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital – The Neuro - at McGill University and McGill University Health Centre, reveals that certain errors in visual perception in people with schizophrenia are consistent with interference or 'noise' in a brain signal known as a corollary discharge. Corollary discharges are found throughout the animal kingdom, from bugs ...

Strain-specific Lyme disease immunity lasts for years, Penn research finds

2014-04-02

Lyme disease, if not treated promptly with antibiotics, can become a lingering problem for those infected. But a new study led by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania has some brighter news: Once infected with a particular strain of the disease-causing bacteria, humans appear to develop immunity against that strain that can last six to nine years.

The finding doesn't give people who have already had the disease license to wander outside DEET-less, however. At least 16 different strains of the Lyme disease bacterium have been shown to infect humans in the United ...

Criticism of violent video games has decreased as technology has improved, gamers age

2014-04-02

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Members of the media and others often have attributed violence in video games as a potential cause of social ills, such as increased levels of teen violence and school shootings. Now, a University of Missouri researcher has found that media acceptance of video game violence has increased as video game technology has improved over time. Greg Perreault, a doctoral student at the MU School of Journalism, examined the coverage of violent video games throughout the 1990s by GamePro Magazine, the most popular video game news magazine during that time period. Perreault ...

Food pantry clients struggle to afford diapers, detergent, other non-food items

2014-04-02

URBANA, Ill. - Many food-insecure families also struggle to afford basic non-food household goods, such as personal care, household, and baby-care products, according to a new University of Illinois study published in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues.

"These families often make trade-offs with other living expenses and employ coping strategies in an effort to secure such household items as toilet paper, toothpaste, soap, or disposable diapers. What's more, nearly three in four low-income families have cut back on food in the past year in order to afford these ...

Strain can alter materials' properties

2014-04-02

In the ongoing search for new materials for fuel cells, batteries, photovoltaics, separation membranes, and electronic devices, one newer approach involves applying and managing stresses within known materials to give them dramatically different properties.

This development has been very exciting, says MIT associate professor of nuclear science and engineering Bilge Yildiz, one of the pioneers of this approach: "Traditionally, we make materials by changing compositions and structures, but we are now recognizing that strain is an additional parameter that we can change, ...

Researchers identify how zinc regulates a key enzyme involved in cell death

2014-04-02

The molecular details of how zinc, an essential trace element of human metabolism, interacts with the enzyme caspase-3, which is central to apoptosis or cell death, have been elucidated in a new study led by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University. The study is featured on the cover of the April issue of the journal Angewandte Chemie's International Edition.

Dysregulation of apoptosis is implicated in cancer and neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer's disease. Zinc is known to affect the process by inhibiting the activity of caspases, which are important ...

The Neanderthal in us

2014-04-02

This news release is available in German. Although Neanderthals are extinct, fragments of their genomes persist in modern humans. These shared regions are unevenly distributed across the genome and some regions are particularly enriched with Neanderthal variants. An international team of researchers led by Philipp Khaitovich of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and the CAS-MPG Partner Institute for Computational Biology in Shanghai, China, show that DNA sequences shared between modern humans and Neanderthals are specifically ...

Men who started smoking before age 11 had fatter sons

2014-04-02

Men who started smoking regularly before the age of 11 had sons who, on average, had 5-10kg more body fat than their peers by the time they were in their teens, according to new research from the Children of the 90s study at the University of Bristol. The researchers say this could indicate that exposure to tobacco smoke before the start of puberty may lead to metabolic changes in the next generation.

The effect, although present, was not seen to the same degree in daughters. Many other factors, including genetic factors and the father's weight, were taken into account ...

Crib mattresses emit potentially harmful chemicals, Cockrell School engineers find

2014-04-02

In a first-of-its-kind study, a team of environmental engineers from the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin found that infants are exposed to high levels of chemical emissions from crib mattresses while they sleep.

Analyzing the foam padding in crib mattresses, the team found that the mattresses release significant amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), potentially harmful chemicals also found in household items such as cleaners and scented sprays.

The researchers studied samples of polyurethane foam and polyester foam padding ...