(Press-News.org) When cannibals ate brains of people who died from prion disease, many of them fell ill with the fatal neurodegenerative disease as well. Likewise, when cows were fed protein contaminated with bovine prions, many of them developed mad cow disease. On the other hand, transmission of prions between species, for example from cows, sheep, or deer to humans, is—fortunately—inefficient, and only a small proportion of exposed recipients become sick within their lifetimes.

A study published on April 3rd in PLOS Pathogens takes a close look at one exception to this rule: bank voles appear to lack a species barrier for prion transmission, and their universal susceptibility turns out to be both informative and useful for the development of strategies to prevent prion transmission.

Prions are misfolded, toxic versions of a protein called PrP, which in its normal form is present in all mammalian species that have been examined. Toxic prions are "infectious"; they can induce existing, properly folded PrP proteins to convert into the disease-associated prion form. Prion diseases are rare, but they share features with more common neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease.

Trying to understand the unusual susceptibility of bank voles to prions from other species, Stanley Prusiner, Joel Watts, Kurt Giles and colleagues, from the University of California in San Francisco, USA, first tested whether the susceptibility is an intrinsic property of the voles' PrP, or whether other factors present in these rodents make them vulnerable.

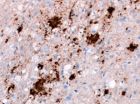

The scientists introduced into mice the gene that codes for the normal bank vole prion protein, thereby generating mice that express bank vole PrP, but not mouse PrP. When these mice get older, some of them spontaneously develop neurologic illness, but in the younger ones the bank vole PrP is in its normal, benign folded state. The scientists then exposed young mice to toxic misfolded prions from 8 different species, including human, cattle, elk, sheep, and hamster.

They found that all of these foreign-species prions can cause prion disease in the transgenic mice, and that the disease develops often more rapidly than it does in bank voles. The latter is likely because the transgenic mice express higher levels of bank vole PrP than are naturally present in the voles.

The results show that the universal susceptibility of bank voles to cross-species prion transmission is an intrinsic property of bank vole PrP. Because the transgenic mice develop prion disease rapidly, the scientists propose that the mice will be useful tools in studying the processes by which toxic prions "convert" healthy PrP and thereby destroy the brain. And because that process is similar across many neurodegenerative diseases, better understanding prion disease development might have broader implications.

INFORMATION:

Please contact plospathogens@plos.org to request more information about our content and topics of interest.

CONTACT:

Joel Watts

e-mail: joel.watts@utoronto.ca

phone: (416) 507-6891

Kurt Giles

e-mail: kgiles@ind.ucsf.edu

phone: (415) 502-7090

Article Link:

http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003990 (link goes lives upon article publication)

Image links:

Bank Vole: http://www.plos.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Pathogens_Prusiner_April3_IMG1.jpg

Cell Stain: http://www.plos.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Watts_PLoSPathog_Apr3_img2.tiff

Image caption: Accumulation of misfolded, toxic prion protein (brown staining) in the brain of a transgenic mouse expressing bank vole PrP and challenged with human variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) prions. Credit: Image courtesy of Dr. Joel Watts.

Authors and Affiliations:

Joel C. Watts, University of California San Francisco, California

Kurt Giles, University of California San Francisco, California

Smita Patel, University of California San Francisco, California

Abby Oehler, University of California San Francisco, California

Stephen J. DeArmond, University of California San Francisco, California

Stanley B. Prusiner, University of California San Francisco, California

Citation: Watts JC, Giles K, Patel S, Oehler A, DeArmond SJ, et al. (2014) Evidence That Bank Vole PrP Is a Universal Acceptor for Prions. PLoS Pathog 10(4): e1003990. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003990

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG021601, AG002132, AG010770, AG031220, and NS064173) as well as by a gift from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation. JCW was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), a K99 grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG042453), and a research grant from the Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

What bank voles can teach us about prion disease transmission and neurodegeneration

2014-04-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Poor quality of life may contribute to kidney disease patients' health problems

2014-04-04

Washington, DC (April 3, 2014) — Kidney disease patients with poor quality of life are at increased risk of experiencing progression of their disease and of developing heart problems, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (JASN). The findings suggest that quality of life measurements may have important prognostic value in these individuals.

Approximately 60 million people globally have chronic kidney disease (CKD). Quality of life has been well-studied in patients with end-stage kidney disease, but not ...

Walking may help protect kidney patients against heart disease and infections

2014-04-04

Washington, DC (April 3, 2014) — Just a modest amount of exercise may help reduce kidney disease patients' risks of developing heart disease and infections, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (JASN).

Heart disease and infection are major complications and the leading causes of death in patients with chronic kidney disease. It is now well established that immune system dysfunction is involved in both of these pathological processes. Specifically, impaired immune function predisposes to infection, while ...

Insomnia may significantly increase stroke risk

2014-04-03

The risk of stroke may be much higher in people with insomnia compared to those who don't have trouble sleeping, according to new research in the American Heart Association journal Stroke.

The risk also seems to be far greater when insomnia occurs as a young adult compared to those who are older, said researchers who reviewed the randomly-selected health records of more than 21,000 people with insomnia and 64,000 non-insomniacs in Taiwan.

They found:

Insomnia raised the likelihood of subsequent hospitalization for stroke by 54 percent over four years.

The incidence ...

Higher total folate intake may be associated with lower risk of exfoliation glaucoma

2014-04-03

BOSTON (April 4, 2014) — Exfoliation glaucoma (EG), caused by exfoliation syndrome, a condition in which white clumps of fibrillar material form in the eye, is the most common cause of secondary open-angle glaucoma and a leading cause of blindness and visual impairment. Effective strategies for preventing this disease are lacking.

Elevated homocysteine, which may enhance exfoliation material formation, is one possible risk factor that has received significant research attention. Research studies demonstrate that high intake of vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and folate ...

Off the shelf, on the skin: Stick-on electronic patches for health monitoring

2014-04-03

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Wearing a fitness tracker on your wrist or clipped to your belt is so 2013.

Engineers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Northwestern University have demonstrated thin, soft stick-on patches that stretch and move with the skin and incorporate commercial, off-the-shelf chip-based electronics for sophisticated wireless health monitoring.

The patches stick to the skin like a temporary tattoo and incorporate a unique microfluidic construction with wires folded like origami to allow the patch to bend and flex without being constrained ...

Geology spans the minute and gigantic, from skeletonized leaves in China to water on mars

2014-04-03

Boulder, Colo., USA – New Geology studies include a mid-Cretaceous greenhouse world; the Vredefort meteoric impact event and the Vredefort dome, South Africa; shallow creeping faults in Italy; a global sink for immense amounts of water on Mars; the Funeral Mountains, USA; insect-mediated skeletonization of fern leaves in China; first-ever tectonic geomorphology study in Bhutan; the Ethiopian Large Igneous Province; the Central Andean Plateau; the Scandinavian Ice Sheet; the India-Asia collision zone; the Snake River Plain; and northeast Brazil.

Highlights are provided ...

Calcium waves help the roots tell the shoots

2014-04-03

MADISON – For Simon Gilroy, sometimes seeing is believing. In this case, it was seeing the wave of calcium sweep root-to-shoot in the plants the University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of botany is studying that made him a believer.

Gilroy and colleagues, in a March 24, 2014 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed what long had been suspected but long had eluded scientists: that calcium is involved in rapid plant cell communication.

It's a finding that has implications for those interested in how plants adapt to and thrive in changing ...

Smoking may dull obese women's ability to taste fat and sugar

2014-04-03

Cigarette smoking among obese women appears to interfere with their ability to taste fats and sweets, a new study shows. Despite craving high-fat, sugary foods, these women were less likely than others to perceive these tastes, which may drive them to consume more calories.

M. Yanina Pepino, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Julie Mennella, PhD, a biopsychologist at the Monell Center in Philadelphia, where the research was conducted, studied four groups of women ages 21 to 41: obese smokers, obese nonsmokers, ...

Dose-escalated hypofractionated IMRT, conventional IMRT for prostate cancer have like side effects

2014-04-03

Fairfax, Va., April 3, 2014—Dose-escalated intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with use of a moderate hypofractionation regimen (72 Gy in 2.4 Gy fractions) can safely treat patients with localized prostate cancer with limited grade 2 or 3 late toxicity, according to a study published in the April 1, 2014 edition of the International Journal of Radiation Oncology · Biology · Physics (Red Journal), the official scientific journal of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

Previous randomized clinical trials have shown that dose-escalated ...

Fences cause 'ecological meltdown'

2014-04-03

NEW YORK (Embargoed – Not for release until 14:00 EST 3 April 2014) Wildlife fences are constructed for a variety of reasons including to prevent the spread of diseases, protect wildlife from poachers, and to help manage small populations of threatened species. Human–wildlife conflict is another common reason for building fences: Wildlife can damage valuable livestock, crops, or infrastructure, some species carry diseases of agricultural concern, and a few threaten human lives. At the same time, people kill wild animals for food, trade, or to defend lives or property, and ...