(Press-News.org) A newly constructed family tree of the hummingbirds, published today in the journal Current Biology, tells a story of a unique group of birds that originated in Europe, passed through Asia and North America, and ultimately found its Garden of Eden in South America 22 million years ago.

These early hummingbirds spread rapidly across the South American continent, evolved iridescent colors – various groups are known today as brilliants, topazes, emeralds and gems – diversified into more than 140 new species in the rising Andes, jumped water gaps to invade North America and the Caribbean, and continue to generate new species today.

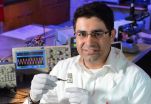

"Our study provides a much clearer picture regarding how and when hummingbirds came to be distributed where they are today," said lead author Jimmy McGuire, a UC Berkeley associate professor of integrative biology and curator of herpetology (reptiles and amphibians) in the campus's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology.

There are now 338 recognized hummingbird species, but that number could double in the next several million years, according to the study's authors, who come from UC Berkeley, Louisiana State University and the universities of New Mexico, Michigan and British Columbia.

"We are not close to being at the maximum number of hummingbird species," McGuire said. "If humans weren't around, they would just continue on their merry way, evolving new species over time."

Hummingbird ancestors arose in Eurasia 42 million years ago

For more than 12 years, McGuire and his colleagues collected DNA data from 451 birds representing 284 species of hummingbirds and their closest relatives, ultimately sequencing six nuclear and mitochondrial genes. They used the data to arrange the living groups in a family tree, and concluded that the branch leading to modern hummingbirds arose about 42 million years ago when they split from their sister group, the swifts and treeswifts. This probably happened in Europe or Asia, where hummingbird-like fossils have been found dating from 28-34 million years ago.

Somehow, he said, hummingbirds found their way to South America, probably via Asia and a land bridge across the Bering Strait to Alaska. They left no survivors in their ancestral lands, but once they hit South America about 22 million years ago, they quickly expanded into new ecological niches and evolved new species represented by nine distinct groups known today as topazes, hermits, mangoes, brilliants, coquettes, mountain gems, bees, emeralds, and the single-species group Patagona (the Giant Hummingbird, Patagona gigas).

About 12 million years ago, the common ancestor of the bee and mountain gem hummingbird groups made the jump into North America, which at the time was still separated from South America by a few hundred miles of water. Once these hummingbirds had "prepared the ground" by initiating co-evolution with North American plants, McGuire said, they were later followed several times by other hummingbird lineages, including representatives of the mangoes and emeralds, and then by many more species when the Isthmus of Panama formed connecting South and North America about 4 million years ago.

About 5 million years ago, hummingbirds invaded the Caribbean, and did so five more times since. One of these groups, the bee hummingbirds, which originated in North America, participated in the Caribbean invasion, and even re-colonized South America alongside existing lineages. This group experienced the highest diversification rates of any hummingbird group – 15 times that of the lowest, the topazes – which is on a par with that of classic examples of rapid adaptation to a new environment (adaptive radiation).

The genetic analysis shows that the diversity of hummingbirds continues to rise today, with the origination rate of new species exceeding extinction rates. And despite the fact that they feed primarily on nectar and tiny insects, some places contain more than 25 species in the same geographic area.

"When it comes to vertebrate animals, hummingbirds are about as diverse as they come," he said.

From herps to hummingbirds

McGuire, a herpetologist whose main interest is the evolution of reptile and amphibian diversity in Southeast Asia, became interested in hummingbird flight by accident while a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. While there he collaborated with Robert Dudley, an expert on hummingbird flight and now a fellow UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology, and Dudley's student, Doug Altshuler, now at the University of British Columbia. They wanted to understand how hummingbirds are able to live at high elevations, including at over 15,000 feet in the Andes Mountains, despite the reduced air density, which makes flying harder. Such a study required, however, that they understand how the various species are related, and McGuire volunteered to do a genetic analysis to construct a phylogeny (the equivalent of a genealogy but for species).

One unanswered question, he said, is how hummingbirds got a toehold in South America at all, since today they are dependent on plants that coevolved with them and developed unique feeding adaptations.

"It is really difficult to imagine how it started, since hummingbirds are involved in this coevolutionary process with plants that has led to specializations we typically associate with hummingbird plants, such as tubular, often red flowers, with dilute nectar," he said. "They drive the evolution of their own ecosystem. The evolution of hummingbirds has profoundly affected the evolution of the New World flora via codiversification."

McGuire hopes to continue hummingbird studies with his colleagues, exploring how they've adapted to a diverse variety of ecological niches and, in particular, how they tolerate reduced oxygen availability at high elevations.

"Everything about hummingbirds is extreme," said McGuire, who initiated work on the current phylogenetic analysis as an assistant professor at Louisiana State University before joining the UC Berkeley faculty in 2003. "They have this incredible hovering flight, with wing beat frequencies of 60 times per second, which is nuts. They have the highest metabolic rate for their size of any vertebrate; they are little machines that run on oxygen at a high rate. They also have the largest hippocampal formation in the brain of any bird, which is tied to spatial learning, presumably because they visit the same flower clusters over and over again, and must remember where and when they most recently slurped the nectar from individual flowers. It is amazing that evolution can take an animal to such extremes."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Dudley and Altshuler, other coauthors are Christopher C. Witt of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; J. V. Remsen, Jr., of Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge; Ammon Corl of UC Berkeley; and Daniel L. Rabosky of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation (DEB 0330750, 0543556, 1146491).

Hummingbird evolution soared after they invaded South America 22 million years ago

High rate of diversification rivaled that of any known group and continues today

2014-04-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Iowa State scientist developing materials, electronics that dissolve when triggered

2014-04-04

AMES, Iowa – A medical device, once its job is done, could harmlessly melt away inside a person's body. Or, a military device could collect and send its data and then dissolve away, leaving no trace of an intelligence mission. Or, an environmental sensor could collect climate information, then wash away in the rain.

It's a new way of looking at electronics: "You don't expect your cell phone to dissolve someday, right?" said Reza Montazami, an Iowa State University assistant professor of mechanical engineering. "The resistors, capacitors and electronics, you don't expect ...

Watching for a black hole to gobble up a gas cloud

2014-04-04

Right now a doomed gas cloud is edging ever closer to the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. These black holes feed on gas and dust all the time, but astronomers rarely get to see mealtime in action.

Northwestern University's Daryl Haggard has been closely watching the little cloud, called G2, and the black hole, called Sgr A*, as part of a study that should eventually help solve one of the outstanding questions surrounding black holes: How exactly do they achieve such supermassive proportions?

She will discuss her latest data at a press ...

Bacteria get new badge as planet's detoxifier

2014-04-04

Las Vegas - A study published recently in PLOS ONE authored by Dr. Henry Sun and his postdoctoral student Dr. Gaosen Zhang of Nevada based research institute DRI provides new evidence that Earth bacteria can do something that is quite unusual. Despite the fact that these bacteria are made of left-handed (L) amino acids, they are able to grow on right-handed (D) amino acids. This DRI study, funded by the NASA Astrobiology Institute and the NASA Exobiology Program, takes a closer look at what these implications mean for studying organisms on Earth and beyond.

"This finding ...

Knowledge, use of IUDs increases when women are offered counseling and 'same-day' service

2014-04-04

PITTSBURGH, April 3, 2014 – Health care clinics should routinely offer same-day placement of intrauterine devices (IUDs) to women seeking emergency contraception, according to researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The study findings, published online in the journal Contraception, demonstrate that providing patient education along with same-day placement service increases both knowledge and use of IUDs three months and a year after women seek emergency contraception.

"Women seeking emergency contraception, who are at very high risk of undesired ...

Researchers empower parents to inspire first-generation college-goers

2014-04-04

(PHILADEPHIA) – Parents who have not attended college are at a disadvantage when it comes to talking about higher education with their kids – yet these are the students who most need a parent's guidance.

A new approach developed and tested by researchers at University of the Pacific's Gladys L. Benerd School of Education may help solve the problem. It was presented today at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. [April 4, 8:15 a.m. EDT, Philadelphia Convention Center Terrace Level, Terrace IV]

"There is a common perception that low-income ...

The Trayvon Martin case: Lessons for education researchers

2014-04-04

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (April 4, 2014) – The 2012 fatal shooting of black teenager Trayvon Martin by his Florida neighbor George Zimmerman sparked a fierce debate about racism and gun violence. Now, researchers are exploring what the controversial case says as well about sexism and violence against women.

Boston College Lynch School of Education Professor Ana M. Martinez Aleman spoke today at the American Educational Research Association annual conference in Philadelphia about the highly politicized debate surrounding the Martin case and the implications for researchers who ...

New risk factors for avalanche trigger revealed

2014-04-04

The amount of snow needed to trigger an avalanche in the Himalayans can be up to four times smaller than in the Alps, according to a new model from a materials scientist at Queen Mary University of London.

The proposed universal model could have implications in better understanding strategies for mitigating natural hazards related to snow and rock avalanches and safeguarding people on mountain villages, roads and ski resorts.

By using a branch of mechanics that aims to understand how cracks spread in solid structures, Professor Nicola Pugno from Queen Mary's School ...

Some long non-coding RNAs are conventional after all

2014-04-04

HEIDELBERG, 4 April 2014 – Not so long ago researchers thought that RNAs came in two types: coding RNAs that make proteins and non-coding RNAs that have structural roles. Then came the discovery of small RNAs that opened up whole new areas of research. Now researchers have come full circle and predicted that some long non-coding RNAs can give rise to small proteins that have biological functions. A recent study in The EMBO Journal describes how researchers have used ribosome profiling to identify several hundred long non-coding RNAs that may give rise to small peptides.

"We ...

'Like a giant elevator to the stratosphere'

2014-04-04

Recent research results show that an atmospheric hole over the tropical West Pacific is reinforcing ozone depletion in the polar regions and could have a significant influence on the climate of the Earth.

An international team of researchers headed by Potsdam scientist Dr. Markus Rex from the German Alfred Wegener Institute has discovered a previously unknown atmospheric phenomenon over the South Seas. Over the tropical West Pacific there is a natural, invisible hole extending over several thousand kilometres in a layer that prevents transport of most of the natural and ...

Guelph researchers solve part of hagfish slime mystery

2014-04-04

VIDEO:

This video shows the internal structure of developing gland thread cells in hagfish slime.

Click here for more information.

University of Guelph researchers have unravelled some of the inner workings of slime produced by one of nature's most bizarre creatures – hagfish.

They've learned how the super-strong and mega-long protein threads secreted by the eel-like animals are organized at the cellular level. Their research was published today in the science journal Nature ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

Flagging claims about cancer treatment on social media as potentially false might help reduce spreading of misinformation, per online experiment with 1,051 US adults

Yawns in healthy fetuses might indicate mild distress

Conservation agriculture, including no-dig, crop-rotation and mulching methods, reduces water runoff and soil loss and boosts crop yield by as much as 122%, in Ethiopian trial

Tropical flowers are blooming weeks later than they used to through climate change

Risk of whale entanglement in fishing gear tied to size of cool-water habitat

Climate change could fragment habitat for monarch butterflies, disrupting mass migration

Neurosurgeons are really good at removing brain tumors, and they’re about to get even better

[Press-News.org] Hummingbird evolution soared after they invaded South America 22 million years agoHigh rate of diversification rivaled that of any known group and continues today