(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Scientists have solved a decades-old medical mystery – and in the process have found a potentially less toxic way to fight invasive fungal infections, which kill about 1.5 million people a year. The researchers say they now understand the mechanism of action of amphotericin, an antifungal drug that has been in use for more than 50 years – even though it is nearly as toxic to human cells as it is to the microbes it attacks.

A report of the new findings appears in Nature Chemical Biology.

"Invasive fungal infections are a very important unmet medical need," said University of Illinois and Howard Hughes Medical Institute chemistry professor Martin Burke, who led the study with chemistry professor Chad Rienstra. "There are about 3 million cases per year and what's striking is that, even in 2014, half the patients who come into the hospital with an invasive fungal infection in their blood die."

More people are killed by invasive fungal infections than by malaria or tuberculosis, Burke said.

Amphotericin (am-foe-TEHR-ih-sin) is the most effective broad-spectrum antifungal drug available, Burke said. But its use is limited by its toxicity to human cells.

"When I was a medical student, they used to call it 'amphoterrible' in the clinic because it has very powerful side effects," he said. "And so you're stuck between having the fungus kill the patient, versus using too much amphotericin, which kills the patient."

Scientists have long sought to make amphotericin less toxic, but have been hindered by an obvious problem: Because it is so hard to study, no one knew exactly how it worked.

"This molecule is one of the most challenging to work with because it has a very complex structure, is poorly soluble and is sensitive to light, oxygen and acid," Burke said.

Amphotericin also interacts with membranes, which are notoriously difficult to study. Many labs, including Burke's, have tried to figure out the three-dimensional structure of amphotericin by crystallizing it, a standard technique. So far, all attempts have failed.

So the team turned to one of the most powerful tools for studying non-crystalline samples: solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, which measures how atomic nuclei respond to changes in a magnetic field.

"NMR is a great technique for detecting signals and interpreting the structural properties of molecules in solution," said Rienstra, who led the NMR work with graduate students Mary Clay and Tom Anderson. But few labs use it to track interactions between small molecules in membranes, he said. "We developed several new NMR experiments to study amphotericin in the presence of membranes."

Previous studies had found evidence that amphotericin opens up ion channels in membranes, perhaps making them more leaky to charged atoms that could disrupt a cell. Most scientists assumed that this was the drug's main mode of action.

But the evidence also suggested that amphotericin interacted with sterols, such as cholesterol in animal cells and ergosterol in yeast. Rienstra and Burke focused on amphotericin's influence on sterols, hypothesizing that this might be a key to its toxicity.

The initial NMR data supported this idea, indicating that very little of the drug – less than 5 percent – actually formed channels in membranes. Using NMR and other experimental tools, the Rienstra/Burke team found that most of the amphotericin aggregates on the exterior of membranes, extracting sterols out of membranes like a sponge. Cell death follows soon after.

"For over 50 years, the mechanism by which amphotericin kills cells has remained a mystery," Burke said. "But we are finally seeing the fog start to clear. This new understanding allows us to focus on how to make this molecule less toxic to human cells."

In a separate study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, Burke and his colleagues appear to have accomplished just that. They developed a derivative of amphotericin that, at least in cell culture, binds to ergosterol in yeast but not to human cholesterol.

"We are very excited about this discovery," Burke said. "But a great deal of work lies ahead to see if this compound has the potential to serve as a less toxic treatment for fungal infections in human patients. At this point, we just have a very promising compound. Most importantly, thanks to the collaboration between these two labs, we now know where to look for solutions to this longstanding problem."

Preclinical trials of the new compound have begun, the researchers said.

INFORMATION:

The National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute supported portions of this work.

Editor's note: To reach Martin Burke, call 217-244-8726; email mdburke@illinois.edu. To reach Chad Rienstra, call 217-244-4655; email rienstra@illinois.edu.

The Nature Chemical Biology paper, "Amphotericin Forms an Extramembranous and Fungicidal Sterol Sponge," is available online or to members of the media from the U. of I. News Bureau. The JACS paper, "C2′-OH of Amphotericin B Plays an Important Role in Binding the Primary Sterol of Human Cells but Not Yeast Cells," is available online or from the U. of I. News Bureau.

Potent, puzzling and (now less) toxic: Team discovers how antifungal drug works

2014-04-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Long-term predictions for Miami sea level rise could be available relatively soon

2014-04-15

Miami could know as early as 2020 how high sea levels will rise into the next century, according to a team of researchers including Florida International University scientist Rene Price.

Price is also affiliated with the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Florida Coastal Everglades Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site, one of 25 such NSF LTER sites in ecosystems from coral reefs to deserts, mountains to salt marshes around the world.

Scientists conclude that sea level rise is one of the most certain consequences of climate change.

But the speed and long-term ...

Study: SSRI use during pregnancy associated with autism and developmental delays in boys

2014-04-15

In a study of nearly 1,000 mother-child pairs, researchers from the Bloomberg School of Public health found that prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a frequently prescribed treatment for depression, anxiety and other disorders, was associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and developmental delays (DD) in boys. The study, published in the online edition of Pediatrics, analyzed data from large samples of ASD and DD cases, and population-based controls, where a uniform protocol was implemented to confirm ASD and DD diagnoses by trained ...

Astronomers: 'Tilt-a-worlds' could harbor life

2014-04-15

A fluctuating tilt in a planet's orbit does not preclude the possibility of life, according to new research by astronomers at the University of Washington, Utah's Weber State University and NASA. In fact, sometimes it helps.

That's because such "tilt-a-worlds," as astronomers sometimes call them — turned from their orbital plane by the influence of companion planets — are less likely than fixed-spin planets to freeze over, as heat from their host star is more evenly distributed.

This happens only at the outer edge of a star's habitable zone, the swath of space around ...

Vitamin D deficiency contributes to poor mobility among severely obese people

2014-04-15

Washington, DC—Among severely obese people, vitamin D may make the difference between an active and a more sedentary lifestyle, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

The study found severely obese people who also were vitamin D-deficient walked slower and were less active overall than their counterparts who had healthy vitamin D levels. Poor physical functioning can reduce quality of life and even shorten lifespans.

Severe obesity occurs when a person's body mass index (BMI) exceeds 40. About ...

Osteoporosis risk heightened among sleep apnea patients

2014-04-15

Washington, DC—A diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea may raise the risk of osteoporosis, particularly among women or older individuals, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

Sleep apnea is a condition that causes brief interruptions in breathing during sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea, the most common form, occurs when a person's airway becomes blocked during sleep. If sleep apnea goes untreated, it can raise the risk for stroke, cardiovascular disease and heart attacks.

"Ongoing sleep disruptions ...

Can refined categorization improve prediction of patient survival in RECIST 1.1?

2014-04-15

In a recent analysis by the RECIST Working Group published in the European Journal of Cancer, EORTC researchers had explored whether a more refined categorization of tumor response or various aspects of progression could improve prediction of overall survival in the RECIST database. They found that modeling target lesion tumor growth did not improve the prediction of overall survival above and beyond that of the other components of progression. The RECIST Working Group includes the EORTC, the United States National Cancer Institute, and the National Cancer Institute of ...

Calcium score predicts future heart disease among adults with little or no risk factors

2014-04-15

LOS ANGELES – (April 15, 2014) – With growing evidence that a measurement of the buildup of calcium in coronary arteries can predict heart disease risk, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute (LA BioMed) researchers found that the process of "calcium scoring" was also accurate in predicting the chances of dying of heart disease among adults with little or no known risk of heart disease.

Previous studies had found that calcium scores were effective in predicting heart disease among adults with known heart disease risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, ...

Earthquake simulation tops 1 quadrillion flops

2014-04-15

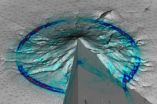

This news release is available in German. Geophysicists use the SeisSol earthquake simulation software to investigate rupture processes and seismic waves beneath the Earth's surface. Their goal is to simulate earthquakes as accurately as possible to be better prepared for future events and to better understand the fundamental underlying mechanisms. However, the calculations involved in this kind of simulation are so complex that they push even super computers to their limits.

In a collaborative effort, the workgroups led by Dr. Christian Pelties at the Department of ...

Cultivating happiness often misunderstood, says Stanford researcher

2014-04-15

The paradox of happiness is that chasing it may actually make us less happy, a Stanford researcher says.

So how does one find happiness? Effective ways exist, according to new research.

One path to happiness is through concrete, specific goals of benevolence – like making someone smile or increasing recycling – instead of following similar but more abstract goals – like making someone happy or saving the environment.

The reason is that when you pursue concretely framed goals, your expectations of success are more likely to be met in reality. On the other hand, broad ...

Lifestyle determines gut microbes

2014-04-15

This news release is available in German. The gut microbiota is responsible for many aspects of human health and nutrition, but most studies have focused on "western" populations. An international collaboration of researchers, including researchers of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has for the first time analysed the gut microbiota of a modern hunter-gatherer community, the Hadza of Tanzania. The results of this work show that Hadza harbour a unique microbial profile with features yet unseen in any other human group, supporting ...