(Press-News.org) DALLAS – April 24, 2014 – Scientific research at UT Southwestern Medical Center previously discovered that the newborn animal heart can heal itself completely, whereas the adult heart lacks this ability. New research by the same team today has revealed why the heart loses its incredible regenerative capability in adulthood, and the answer is quite simple – oxygen.

Yes, oxygen. It is well-known that a major function of the heart is to circulate oxygen-rich blood throughout the body. But at the same time, oxygen is a highly reactive, nonmetallic element and oxidizing agent that readily forms toxic substances with many other compounds. This latter property has now been found to underlie the loss of regenerative capacity in the adult heart.

This groundbreaking new finding, published in today's issue of Cell, finds that the oxygen-rich postnatal environment results in cell cycle arrest of cardiomyocytes, or heart cells.

"Knowing the key mechanism that turns the heart's regenerative capacity off in newborns tells us how we might discover methods to reawaken that capacity in the adult mammalian heart," said Dr. Hesham Sadek, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine at UT Southwestern and senior author of the study.

Due to the oxygen-rich atmosphere experienced immediately after birth, heart cells build up mitochondria – the powerhouse of the cell – which results in increased oxidization. The mass production of oxygen radicals by mitochondria damages DNA and, ultimately, causes cell cycle arrest.

"We have uncovered a previously unrecognized protective mechanism that mediates cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest and that arises as a consequence of oxygen-dependent aerobic metabolism," said Dr. Sadek.

Physiologically speaking, Dr. Sadek said, mammals likely had to make the choice early on between being energy efficient or retaining the heart's ability to regenerate.

"The choice was clear," said Dr. Sadek. "More than any organ in the body, the heart needs to be energy efficient in order to pump blood throughout life."

Heart muscle contains the highest amount of mitochondria in the body and consumes 30 percent of the body's total oxygen in a resting state alone. Unfortunately, the energy that comes from massive oxygen consumption comes with a price in the form of oxidation of DNA that makes the heart cells unable to divide and regenerate.

Dr. Sadek, along with co-first authors Dr. Bao "Robyn" Puente, postdoctoral trainee in Pediatrics, and Dr. Wataru Kimura, visiting senior researcher in Internal Medicine, found that if they subjected mice to a low-oxygen atmosphere, the cardiomyocytes divided longer than normal. The opposite was true when mice were born in a higher-oxygenated atmosphere. In that case, the cardiomyocytes stopped dividing earlier than normal.

This study comes on the heels of findings published in the Feb. 25, 2011, edition of Science, in which Dr. Sadek found that if a portion of a mouse heart was removed during the first week after birth, that portion grew back wholly and correctly. In contrast, an adult heart was irreversibly damaged by removal of even a small amount of tissue.

Because the adult mammal's heart is not able to regenerate following injury, this represents a major barrier in cardiovascular medicine. Having a promising new understanding of what arrests cardiomyocyte cell cycle could be an important component of cardiomyocyte proliferation-based therapeutic approaches.

INFORMATION:

Funding sources for this research include NASA, the European Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, the Fondation Leducq, the American Heart Association, the Foundation for Heart Failure Research, New York, and the National Institutes of Health.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution's faculty includes many distinguished members, including five who have been awarded Nobel Prizes since 1985. Numbering more than 2,700, the faculty is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide medical care in 40 specialties to nearly 91,000 hospitalized patients and oversee more than 2 million outpatient visits a year.

Oxygen diminishes the heart's ability to regenerate, researchers discover

2014-04-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study helps to explain why breast cancer often spreads to the lung

2014-04-24

New research led by Alison Allan, PhD, a scientist at Western University and the Lawson Health Research Institute, shows why breast cancer often spreads or metastasizes to the lung.

Breast cancer is the number one diagnosed cancer and the number two cause of cancer-related deaths among women in North America. If detected early, traditional chemotherapy and radiation have a high success rate, but once the disease spreads beyond the breast, many conventional treatments fail. In particular, the lung is one of the most common and deadly sites of breast cancer metastasis ...

Parents of severely ill children see benefits as caregivers, says study

2014-04-24

Benefits often coexist with the negative and stressful outcomes for parents who have a child born with or later diagnosed with a life-limiting illness, says a recent study led by a researcher at the University of Waterloo.

While the challenges are numerous and life-changing and stress levels high, the vast majority of parents who participated in the Waterloo-led research reported positive outcomes as well, a phenomenon known as posttraumatic growth. The findings appear in the most recent issue of the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry.

"What is pivotal is the meaning ...

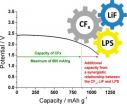

'Double-duty' electrolyte enables new chemistry for longer-lived batteries

2014-04-24

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., April 24, 2014 — Researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have developed a new and unconventional battery chemistry aimed at producing batteries that last longer than previously thought possible.

In a study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, ORNL researchers challenged a long-held assumption that a battery's three main components -- the positive cathode, negative anode and ion-conducting electrolyte -- can play only one role in the device.

The electrolyte in the team's new battery design has ...

Cell resiliency surprises scientists

2014-04-24

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- New research shows that cells are more resilient in taking care of their DNA than scientists originally thought. Even when missing critical components, cells can adapt and make copies of their DNA in an alternative way.

In a study published in this week's Cell Reports, a team of researchers at Michigan State University showed that cells can grow normally without a crucial component needed to duplicate their DNA.

"Our genetic information is stored in DNA, which has to be continuously monitored for damage and copied for growth," said Kefei Yu, ...

Vanderbilt study finds physical signs of depression common among ICU survivors

2014-04-24

Depression affects more than one out of three survivors of critical illness, according to a Vanderbilt study released in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, and the majority of patients experience their symptoms physically rather than mentally.

It is one of the largest studies to investigate the mental health and functional outcomes of critical care survivors, according to lead author James Jackson, Psy.D., assistant professor of Medicine, and it highlights a significant public health issue, with roughly 5 million patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) in the United ...

Study: Altruistic adolescents less likely to become depressed

2014-04-24

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — It is better to give than to receive – at least if you're an adolescent and you enjoy giving, a new study suggests.

The study found that 15- and 16-year-olds who find pleasure in pro-social activities, such as giving their money to family members, are less likely to become depressed than those who get a bigger thrill from taking risks or keeping the money for themselves.

The researchers detail their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study focused on the ventral striatum, a brain region that regulates feelings of ...

Take notes by hand for better long-term comprehension

2014-04-24

Dust off those Bic ballpoints and college-ruled notebooks — research shows that taking notes by hand is better than taking notes on a laptop for remembering conceptual information over the long term. The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Walk into any university lecture hall and you're likely to see row upon row of students sitting behind glowing laptop screens. Laptops in class have been controversial, due mostly to the many opportunities for distraction that they provide (online shopping, browsing ...

Amazon rainforest survey could improve carbon offset schemes

2014-04-24

Carbon offsetting initiatives could be improved with new insights into the make-up of tropical forests, a study suggests.

Scientists studying the Amazon Basin have revealed unprecedented detail of the size, age and species of trees across the region by comparing satellite maps with hundreds of field plots.

The findings will enable researchers to assess more accurately the amount of carbon each tree can store. This is a key factor in carbon offset schemes, in which trees are given a cash value according to their carbon content, and credits can be traded in exchange ...

The blood preserved in the pumpkin did not belong to Louis XVI

2014-04-24

The work has been published in the Scientific Reports journal.

CSIC researcher Carles Lalueza-Fox, from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (a joint centre of CSIC and Pompeu Fabra University-UPF), explains: "When the Y chromosome of three living Bourbons was decoded and we saw that it did not match with the DNA recovered from the pumpkin in 2010, we decided to sequence the complete genome and to make a functional interpretation in order to see if the blood could actually belong to Louis XVI".

The functional genome analysis was based on two main points, the genealogical ...

Study supports safety of antimicrobial peptide-coated contact lenses

2014-04-24

Philadelphia, Pa. (April 24, 2014) - Contact lenses coated with an antimicrobial peptide could help to lower the risk of contact lens-related infections, reports a study in Optometry and Vision Science, official journal of the American Academy of Optometry. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

Studies in animals and now humans support the biocompatibility and safety of lenses coated with the antimicrobial peptide melimine, according to the new research by Debarun Dutta, B.Optom, of The University of New South Wales, ...