(Press-News.org) The drive to develop ultrasmall and ultrafast electronic devices using a single atomic layer of semiconductors, such as transition metal dichalcogenides, has received a significant boost. Researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have recorded the first observations of a strong nonlinear optical resonance along the edges of a single layer of molybdenum disulfide. The existence of these edge states is key to the use of molybdenum disulfide in nanoelectronics, as well as a catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction in fuel cells, desulfurization and other chemical reactions.

"We observed strong nonlinear optical resonances at the edges of a two-dimensional crystal of molybdenum disulfide" says Xiang Zhang, a faculty scientist with Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division who led this study. "These one-dimensional edge states are the result of electronic structure changes and may enable novel nanoelectronics and photonic devices. These edges have also long been suspected to be the active sites for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction in energy applications. We also discovered extraordinary second harmonic light generation properties that may be used for the in situ monitoring of electronic changes and chemical reactions that occur at the one-dimensional atomic edges."

Zhang, who also holds the Ernest S. Kuh Endowed Chair Professor at the University of California (UC) Berkeley and directs the National Science Foundation's Nano-scale Science and Engineering Center, is the corresponding author of a paper in Science describing this research. The paper is titled "Edge Nonlinear Optics on a MoS2 Atomic Monolayer." Co-authors are Xiaobo Yin, Ziliang Ye, Daniel Chenet, Yu Ye, Kevin O'Brien and James Hone.

Emerging two-dimensional semiconductors are prized in the electronics industry for their superior energy efficiency and capacity to carry much higher current densities than silicon. Only a single molecule thick, they are well-suited for integrated optoelectronic devices. Until recently, graphene has been the unchallenged superstar of 2D materials, but today there is considerable attention focused on 2D semiconducting crystals that consist of a single layer of transition metal atoms, such as molybdenum, tungsten or niobium, sandwiched between two layers of chalcogen atoms, such as sulfur or selenium. Featuring the same flat hexagonal "honeycombed" structure as graphene and many of the same electrical advantages, these transition metal dichalcogenides, unlike graphene, have direct energy bandgaps. This facilitates their application in transistors and other electronic devices, particularly light-emitting diodes.

Full realization of the vast potential of transition metal dichalcogenides will only come with a better understanding of the domain orientations of their crystal structures that give rise to their exceptional properties. Until now, however, experimental imaging of these three-atom-thick structures and their edges have been limited to scanning tunneling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy, technologies that are often difficult to use. Nonlinear optics at the crystal edges and boundaries enabled Zhang and his collaborators to develop a new imaging technique based on second-harmonic generation (SHG) light emissions that can easily capture the crystal structures and grain orientations with an optical microscope.

"Our nonlinear optical imaging technique is a non-invasive, fast, easy metrologic approach to the study of 2D atomic materials," says Xiaobo Yin, the lead author of the Science paper and a former member of Zhang's research group who is now on the faculty at the University of Colorado, Boulder. "We don't need to prepare the sample on any special substrate or vacuum environment, and the measurement won't perturb the sample during the imaging process. This advantage allows for in-situ measurements under many practical conditions. Furthermore, our imaging technique is an ultrafast measurement that can provide critical dynamic information, and its instrumentation is far less complicated and less expensive compared with scanning tunneling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy."

For the SHG imaging of molybdenum disulfide, Zhang and his collaborators illuminated sample membranes that are only three atoms thick with ultrafast pulses of infrared light. The nonlinear optical properties of the samples yielded a strong SHG response in the form of visible light that is both tunable and coherent. The resulting SHG-generated images enabled the researchers to detect "structural discontinuities" or edges along the 2D crystals only a few atoms wide where the translational symmetry of the crystal was broken.

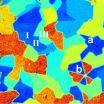

"By analyzing the polarized components of the SHG signals, we were able to map the crystal orientation of the molybdenum disulfide atomic membrane," says Ziliang Ye, the co-lead author of the paper and current member of Zhang's research group. "This allowed us to capture a complete map of the crystal grain structures, color-coded according to crystal orientation. We now have a real-time, non-invasive tool that allows us explore the structural, optical, and electronic properties of 2D atomic layers of transition metal dichalcogenides over a large area."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science through the Energy Frontier Research Center program, and by the U.S.

Air Force Office of Scientific Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Edgy look at 2-D molybdenum disulfide

Berkeley Lab researchers observe 1-D edge states critical to nanoelectronic and photonic applications

2014-05-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Some Ohio butterflies threatened by rising temperatures

2014-05-01

The combined heat from climate change and urbanization is likely to reduce the number of eastern swallowtails and other native butterflies in Ohio and promote the spread of invasive relatives, a new study led by a Case Western Reserve University researcher shows.

Among 20 species monitored by the Ohio Lepidopterists society, eight showed significant delays in important early lifecycle events when the two factors were combined—a surprising response that may render the eight unfit for parts of the state where they now thrive.

Butterflies serve as important indicator ...

Whales hear us more than we realize

2014-05-01

RICHLAND, Wash. – Killer whales and other marine mammals likely hear sonar signals more than we've known.

That's because commercially available sonar systems, which are designed to create signals beyond the range of hearing of such animals, also emit signals known to be within their hearing range, scientists have discovered.

The sound is likely very soft and audible only when the animals are within a few hundred meters of the source, say the authors of a new study. The signals would not cause any actual tissue damage, but it's possible that they affect the behavior ...

Penn Vet research identifies compounds that control hemorrhagic viruses

2014-05-01

People fear diseases such as Ebola, Marburg, Lassa fever, rabies and HIV for good reason; they have high mortality rates and few, if any, possible treatments. As many as 90 percent of people who contract Ebola, for instance, die of the disease.

Facing this gaping need for therapies, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine teamed with colleagues to focus on identifying and developing compounds that could reduce a virus' ability to spread infection. In two studies published in the Journal of Virology, the researchers have identified several ...

Hubble astronomers check the prescription of a cosmic lens

2014-05-01

Two teams of astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have discovered three distant exploding stars that have been magnified by the immense gravity of foreground galaxy clusters, which act like "cosmic lenses". These supernovae are the first of their type ever to be observed magnified in this way and they offer astronomers a powerful tool to check the prescription of these massive lenses.

Massive clusters of galaxies act as "gravitational lenses" because their powerful gravity bends light passing through them [1]. This lensing phenomenon makes faraway objects ...

The real difference between how men and women choose their partners

2014-05-01

This news release is available in French. In Concordia's study, men responded more strongly to the "framing effect" when physical attractiveness was described.

A hamburger that's 90 per cent fat-free sounds a lot better than one with 10 per cent fat. And even when the choices are the same, humans are hard-wired to prefer the more positive option.

This is because of what's known as the "framing effect," a principle that new research from Concordia has proved applies to mate selection, too.

The study — co-authored by Concordia marketing professor Gad Saad and Wilfrid ...

Casualties get scant attention in wartime news, with little change since World War I

2014-05-01

The human costs of America's wars have received scant attention in daily war reporting – through five major conflicts going back a century – says an extensive and first-of-its-kind study of New York Times war coverage being published this month.

It's timely research given the major anniversaries this year for three of those conflicts.

No matter the war, the number of dead and wounded, the degree of government censorship, the type of warfare, or whether volunteers or draftees are doing the fighting, casualties get little mention, says Scott Althaus, a University of Illinois ...

Can money buy happiness? For some, the answer is no

2014-05-01

SAN FRANCISCO, May 1, 2014 -- Many shoppers, whether they buy material items or life experiences, are no happier following the purchase than they were before, according to a new study from San Francisco State University.

Although previous research has shown experiences create greater happiness for buyers, the study suggests that certain material buyers -- those who tend to purchase material goods -- may be an exception to this rule. The study is detailed in an article to be published in the June edition of the Journal of Research in Personality.

"Everyone has been told ...

Scientists propose amphibian protection

2014-05-01

An ecological strategy developed by four researchers, including two from Simon Fraser University, aims to abate the grim future that the combination of two factors could inflict on many amphibians, including frogs and salamanders.

A warming climate and the introduction of non-native fish in the American West's mountainous areas are combining to threaten the habitat that this ecologically critical group of species needs to thrive.

Previous studies predict the combined effect of climate change and non-native fish could cause amphibian populations to decline and even ...

Noncombat injury top reason for pediatric care by military surgeons in Afghanistan, Iraq

2014-05-01

Chicago (May 1, 2014): Noncombat-related injury—caused by regular car accidents, falls and burns—is the most common reason for pediatric admissions to U.S. military combat hospitals in both Iraq and Afghanistan reveals new study findings published in the May issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

In recent years, research has shown that Army hospitals treat a significant number of wounded and sick children in Iraq and Afghanistan. But the new analysis explores the nature of that care, determining how many children were treated for combat-related injuries ...

Bureau of Reclamation Water Management video series highlights collaborative research

2014-05-01

WASHINGTON - The Bureau of Reclamation is releasing a series of videos summarizing collaborative research addressing climate change and variability impacts, estimating flood and drought hazards, and improving streamflow prediction. This information was presented in January at the Second Annual Progress Meeting on Reclamation Climate and Hydrology Research.

"For more than 100 years, Reclamation and its partners have developed the tools to guide a sustainable water and power future for the West," said Acting Commissioner Lowell Pimley. "This video series summarizes collaborative ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

When safety starts with a text message

CSIC develops an antibody that protects immune system cells in vitro from a dangerous hospital-acquired bacterium

New study challenges assumptions behind Africa’s Green Revolution efforts and calls for farmer-centered development models

Immune cells link lactation to long-lasting health

Evolution: Ancient mosquitoes developed a taste for early hominins

Pickleball players’ reported use of protective eyewear

Changes in organ donation after circulatory death in the US

[Press-News.org] Edgy look at 2-D molybdenum disulfideBerkeley Lab researchers observe 1-D edge states critical to nanoelectronic and photonic applications