(Press-News.org) Scientists at USC have definitively demonstrated that large sets of variations in the genetic code that do not individually appear to have much effect can collectively produce significant changes in an organism's physical characteristics.

Studying the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, USC's Matthew B. Taylor and Ian M. Ehrenreich found that the effects of these genetic variants can depend on four or more other variants in an individual's genome.

Most genetic analyses of heritable physical characteristics, including genome-wide association studies in human populations, focus on so-called "additive" variants that have effects that occur regardless of the organism's genetic background. Taylor and Ehrenreich, however, found that higher-order interactions of five or more places along the genome can have major impacts, and may help explain the so-called "missing heritability" problem, in which additive genetic variants do not entirely explain many inherited diseases and traits.

"Studies focused only on additive effects often explain just a fraction of the genetic basis of many traits. The question is, what are we missing?" said Ehrenreich, assistant professor of molecular biology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and corresponding author of a paper on the study that was published by PLOS Genetics on May 1.

An alternative view of Taylor and Ehrenreich's findings is that genetic variants that have the potential to cause major changes in an organism's phenotype can be completely canceled out if they occur in the "wrong" genomic background.

"It's exciting to provide a characterized example of how genetic background can influence the effects of mutations. We hope that this will open the door for future studies to tease apart how these complex interactions happen," said Taylor, a PhD student in the Molecular and Computational Biology Section at USC.

Their work could impact genetic mapping studies, suggesting that researchers will need to take an approach to understanding the genotype-phenotype relationship that encompasses complex non-additive effects.

Taylor and Ehrenreich plan to take a closer look at the molecular mechanisms that underlie these interactions, in the hopes of providing basic insights into how they occur in biological systems.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by grant R21AI108939 from the National Institutes of Health and grant MCB1330874 from the National Science Foundation.

Small variations in genetic code can team up to have a bi

USC scientists find that complex interactions among genetic variants have major ramifications -- and may help explain the 'missing heritability' problem

2014-05-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New myeloma-obesity research shows drugs can team with body's defenses

2014-05-02

Obesity increases the risk of myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells that accumulate inside the bones.

And with current obesity trends in the United States and especially in South Texas, that's ominous.

"I'm predicting an increase in multiple myeloma," said Edward Medina, M.D., Ph.D., "and with the obesity problems we see in the Hispanic population, there could be a serious health disparity on the horizon."

Dr. Medina, a hematopathologist and assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, is looking ...

AGA unveils latest advances in GI research at DDW 2014

2014-05-02

Chicago, IL (May 2, 2014) — International leaders in the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology will gather together for Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2014, the largest and most prestigious gastroenterology meeting, from May 3 to 6, 2014, at McCormick Place in Chicago, IL. DDW is jointly sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

AGA researchers will present ...

Nature's chemical diversity reflected in Swedish lakes

2014-05-02

It's not only the biology of lakes that varies with the climate and other environmental factors, it's also their chemistry. More knowledge about this is needed to understand the ecology of lakes and their role in the carbon cycle and the climate. Today an international research group led by Uppsala University is publishing a comprehensive study of the composition of organic compounds in the prestigious journal Nature Communications.

- Lake water is like a very thin broth with several thousand ingredients in the recipe, all with different properties. At the same time ...

Stimulated mutual annihilation

2014-05-01

Twenty years ago, Philip Platzman and Allen Mills, Jr. at Bell Laboratories proposed that a gamma-ray laser could be made from a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) of positronium, the simplest atom made of both matter and antimatter (1). That was a year before a BEC of any kind of atom was available in any laboratory. Today, BECs have been made of 13 different elements, four of which are available in laboratories of the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) (2), and JQI theorists have turned their attention to prospects for a positronium gamma-ray laser.

In a study published ...

Syracuse University physicists confirm existence of new type of meson

2014-05-01

Physicists in the College of Arts and Sciences at Syracuse University have made several important discoveries regarding the basic structure of mesons—subatomic particles long thought to be composed of one quark and one antiquark and bound together by a strong interaction.

Recently, Professor Tomasz Skwarnicki and a team of researchers proved the existence of a meson named Z(4430), with two quarks and two antiquarks, using data from the Large Hadron Collidor beauty (LHCb) Collaboration at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland. This tetraquark state was first discovered in Japan ...

Investigators find something fishy with classical evidence for dietary fish recommendation

2014-05-01

Philadelphia, PA, May 1, 2014 – Oily fish are currently recommended as part of a heart healthy diet. This guideline is partially based on the landmark 1970s study from Bang and Dyerberg that connected the low incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) among the Eskimos of Greenland to their diet, rich in whale and seal blubber. Now, researchers have found that Eskimos actually suffered from CAD at the same rate as their Caucasian counterparts, meaning there is insufficient evidence to back Bang and Dyerberg's claims. Their findings are published in the Canadian Journal ...

Atypical form of Alzheimer's disease may be present in a more widespread number of patients

2014-05-01

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Neuroscientists at Mayo Clinic in Florida have defined a subtype of Alzheimer's disease (AD) that they say is neither well recognized nor treated appropriately.

The variant, called hippocampal sparing AD, made up 11 percent of the 1,821 AD-confirmed brains examined by Mayo Clinic researchers — suggesting this subtype is relatively widespread in the general population. The Alzheimer's Association estimates that 5.2 million Americans are living with AD. And with nearly half of hippocampal sparing AD patients being misdiagnosed, this could mean that ...

JCI online ahead of print table of contents for May 1, 2014

2014-05-01

Balancing protein turnover in the heart

Alterations in the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), which tags proteins for degradation, underlies some cardiomyopathies and age-related cardiac dysfunction. In the heart, the UPS is essential for the precise balance between cardiomyocyte atrophy and hypertrophy. In skeletal muscle, the E3 ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 promotes atrophy by targeting hypertrophy-associated proteins for degradation; however, a role for atrogin-1 in cardiac proteostasis is not clear. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Marco Sandri, ...

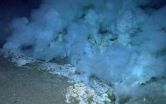

Undersea warfare: Viruses hijack deep-sea bacteria at hydrothermal vents

2014-05-01

More than a mile beneath the ocean's surface, as dark clouds of mineral-rich water billow from seafloor hot springs called hydrothermal vents, unseen armies of viruses and bacteria wage war.

Like pirates boarding a treasure-laden ship, the viruses infect bacterial cells to get the loot: tiny globules of elemental sulfur stored inside the bacterial cells.

Instead of absconding with their prize, the viruses force the bacteria to burn their valuable sulfur reserves, then use the unleashed energy to replicate.

"Our findings suggest that viruses in the dark oceans indirectly ...

Excessive regulations turning scientists into bureaucrats

2014-05-01

Excessive regulations are consuming scientists' time and wasting taxpayer dollars, says a report released today by the National Science Board (NSB), the policymaking body of the National Science Foundation and advisor to Congress and the President.

"Regulation and oversight of research are needed to ensure accountability, transparency and safety," said Arthur Bienenstock, chair of the NSB task force that examined the issue. "But excessive and ineffective requirements take scientists away from the bench unnecessarily and divert taxpayer dollars from research to superfluous ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

[Press-News.org] Small variations in genetic code can team up to have a biUSC scientists find that complex interactions among genetic variants have major ramifications -- and may help explain the 'missing heritability' problem