(Press-News.org) A newly identified difference between the brains of women and men with multiple sclerosis (MS) may help explain why so many more women than men get the disease, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

In recent years, the diagnosis of MS has increased more rapidly among women, who get the disorder nearly four times more than men. The reasons are unclear, but the new study is the first to associate a sex difference in the brain with MS.

The findings appear May 8 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

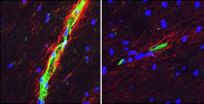

Studying mice and people, the researchers found that females susceptible to MS produce higher levels of a blood vessel receptor protein, S1PR2, than males and that the protein is present at even higher levels in the brain areas that MS typically damages.

"It was a 'Bingo!' moment – our genetic studies led us right to this receptor," said senior author Robyn Klein, MD, PhD. "When we looked at its function in mice, we found that it can determine whether immune cells cross blood vessels into the brain. These cells cause the inflammation that leads to MS."

An investigational MS drug currently in clinical trials blocks other receptors in the same protein family but does not affect S1PR2. Klein recommended that researchers work to develop a drug that disables S1PR2.

MS is highly unpredictable, flaring and fading at irregular intervals and producing a hodgepodge of symptoms that includes problems with mobility, vision, strength and balance. More than 2 million people worldwide have the condition.

In MS, inflammation caused by misdirected immune cells damages a protective coating that surrounds the branches of nerve cells in the brain and spinal column. This leads the branches to malfunction and sometimes causes them to wither away, disrupting nerve cell communication necessary for normal brain functions like movement and coordination.

For the new research, Klein studied a mouse model of MS in which the females get the disease more often than the males. The scientists compared levels of gene activity in male and female brains. They also looked at gene activity in the regions of the female brain that MS damages and in other regions the disorder typically does not harm.

They identified 20 genes that were active at different levels in vulnerable female brain regions. Scientists don't know what 16 of these genes do. Among the remaining genes, the increased activity of S1PR2 stood out because researchers knew from previous studies that the protein regulates how easy it is for cells and molecules to pass through the walls of blood vessels.

Additional experiments showed that S1PR2 opens up the blood-brain barrier, a structure in the brain's blood vessels that tightly regulates the materials that cross into the brain and spinal fluid. This barrier normally blocks potentially harmful substances from entering the brain. Opening it up likely allows the inflammatory cells that cause MS to get into the central nervous system.

When the researchers tested brain tissue samples obtained from 20 patients after death, they found more S1PR2 in MS patients' brains than in people without the disorder. Brain tissue from females also had higher levels of S1PR2 than male brain tissue. The highest levels of S1PR2 were found in the brains of two female patients whose symptoms flared and faded irregularly, a pattern scientists call relapsing and remitting MS.

Klein is collaborating with chemists to design a tracer that will allow scientists to monitor S1PR2 levels in the brains of people while they are living. She hopes this will lead to a fuller understanding of how S1PR2 contributes to MS.

"This is an exciting first step in resolving the mystery of why MS rates are dramatically higher in women and in finding better ways to reduce the incidence of this disorder and control symptoms," said Klein, associate professor of medicine. Klein also is an associate professor of pathology and immunology and of neurobiology and anatomy.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by NIH/NINDS grants R01 NS052632 (to RSK), P01 NS059560 (to AHC and RSK) and grants from the Multiple Sclerosis Society (to RSK). BPD is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1143954), LCO is supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral NRSA award (1F32NS0748424-01), LP is a Harry Weaver Neuroscience Scholar of the National MS Society, USA.

Cruz-Orengo L, Daniels BP, Dorsey D, Basak SA, Grajales-Reyes JG, McCandless EE, Piccio L, Schmidt RE, Cross AH, Crosby SD, Klein RS. Sexually S1PR2 expression enhances susceptibility to CNS autoimmunity. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, online May 8, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Study helps explain why MS is more common in women

2014-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Immune cells found to fuel colon cancer stem cells

2014-05-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A subset of immune cells directly target colon cancers, rather than the immune system, giving the cells the aggressive properties of cancer stem cells.

So finds a new study that is an international collaboration among researchers from the United States, China and Poland.

"If you want to control cancer stem cells through new therapies, then you need to understand what controls the cancer stem cells," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of surgery, immunology and biology at the University of Michigan Medical ...

What doesn't kill you may make you live longer

2014-05-08

What is the secret to aging more slowly and living longer? Not antioxidants, apparently.

Many people believe that free radicals, the sometimes-toxic molecules produced by our bodies as we process oxygen, are the culprit behind aging. Yet a number of studies in recent years have produced evidence that the opposite may be true.

Now, researchers at McGill University have taken this finding a step further by showing how free radicals promote longevity in an experimental model organism, the roundworm C. elegans. Surprisingly, the team discovered that free radicals – also ...

Population genomics study provides insights into how polar bears adapt to the Arctic

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014, Shenzhen, China – In a paper published in the May 8 issue of the journal Cell as the cover story, researches from BGI, University of California, University of Copenhagen and other institutes presented the first polar bear genome and their new findings about how polar bear successfully adapted to life in the high Arctic environment, and its demographic history throughout the history of its adaptation.

Polar bears are at the top of the food chain, and spend most of their lifetimes on the sea ice largely within the Arctic Circle. They were well known to the ...

How immune cells use steroids

2014-05-08

Hinxton, 8 May 2014 – Researchers at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute have discovered that some immune cells turn themselves off by producing a steroid. The findings, published in Cell Reports, have implications for the study of cancers, autoimmune diseases and parasitic infections.

If you've ever used a steroid, for example cortisone cream on eczema, you'll have seen first-hand how efficient steroids are at suppressing the immune response. Normally, when your body senses that immune cells have finished their job, ...

Just keep your promises: Going above and beyond does not pay off

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014 - If you are sending Mother's Day flowers to your mom this weekend, chances are you opted for guaranteed delivery: the promise that they will arrive by a certain time. Should the flowers not arrive in time, you will likely feel betrayed by the sender for breaking their promise. But if they arrive earlier, you likely will be no happier than if they arrive on time, according to new research. The new work suggests that we place such a high premium on keeping a promise that exceeding it confers little or no additional benefit.

Whether we make them with a person ...

Universal neuromuscular training an inexpensive, effective way to reduce

2014-05-08

ROSEMENT, Ill.─As participation in high-demand sports such as basketball and soccer has increased over the past decade, so has the number of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in teens and young adults. In a study appearing today in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) (a research summary was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in March), researchers found that universal neuromuscular training for high school and college-age athletes—which focuses on the optimal way to bend, jump, land and pivot the knee—is ...

Collaboration between psychologists and physicians important to improving primary health care

2014-05-08

WASHINGTON - Primary care teams that include both psychologists and physicians would help address known barriers to improved primary health care, including missed diagnoses, a lack of attention to behavioral factors and limited patient access to needed care, according to health care experts writing in a special issue of American Psychologist, the flagship journal of the American Psychological Association.

"At the heart of the new primary care team is a partnership between a primary care clinician and a psychologist or other mental health professional. The team works together ...

Small mutation changes brain freeze to hot foot

2014-05-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- Ice cream lovers and hot tea drinkers with sensitive teeth could one day have a reason to celebrate a new finding from Duke University researchers. The scientists have found a very small change in a single protein that turns a cold-sensitive receptor into one that senses heat.

Understanding sensation and pain at this level could lead to more specific pain relievers that wouldn't affect the central nervous system, likely producing less severe side effects than existing medications, said Jörg Grandl, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurobiology in Duke's ...

Statins given early decrease progression of kidney disease

2014-05-08

AURORA, Colo. (May 8, 2014) - Results from a study by University of Colorado School of Medicine researchers show that pravastatin, a medicine widely used for treatment of high cholesterol, also slows down the growth of kidney cysts in children and young adults with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).

ADPKD is the most common potentially lethal hereditary kidney disease, affecting at least 1 in 1000 people. ADPKD is characterized by progressive kidney enlargement due to cyst growth, which results in loss of kidney function over time. At one time, ADPKD ...

Mummy-making wasps discovered in Ecuador

2014-05-08

Some Ecuadorian tribes were famous for making mummified shrunken heads from the remains of their conquered foes. Field work in the cloud forests of Ecuador by Professor Scott Shaw, University of Wyoming, Laramie, and colleagues, has resulted in the discovery of 24 new species of Aleiodes wasps that mummify caterpillars. The research by Eduardo Shimbori, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil, and Scott Shaw, was recently published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

Among the 24 new insect species described by Shimbori and Shaw, several were named after famous people ...