(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

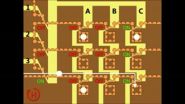

This is a microscopic view of the new microchip-like technology sorting and storing magnetic particles in a three-by-three array.

Click here for more information.

DURHAM, N.C. -- A U.S. and Korean research team has developed a chip-like device that could be scaled up to sort and store hundreds of thousands of individual living cells in a matter of minutes. The system is similar to a random access memory chip, but it moves cells rather than electrons.

Researchers at Duke University and Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) in the Republic of Korea hope the cell-sorting system will revolutionize research by allowing the fast, efficient control and separation of individual cells that could then be studied in vast numbers.

"Most experiments grind up a bunch of cells and analyze genetic activity by averaging the population of an entire tissue rather than looking at the differences between single cells within that population," said Benjamin Yellen, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke's Pratt School of Engineering. "That's like taking the eye color of everyone in a room and finding that the average color is grey, when not a single person in the room has grey eyes. You need to be able to study individual cells to understand and appreciate small but significant differences in a similar population."

The study appears online May 14 in Nature Communications.

Yellen and his collaborator, Cheol Gi Kim of DGIST, printed thin electromagnetic components like those found on microchips onto a slide. These patterns create magnetic tracks and elements like switches, transistors and diodes that guide magnetic beads and single cells tagged with magnetic nanoparticles through a thin liquid film.

Like a series of small conveyer belts, localized rotating magnetic fields move the beads and cells along specific directions etched into a track, while built-in switches direct traffic to storage sites on the chip. The result is an integrated circuit that controls small magnetic objects much like the way electrons are controlled on computer chips.

In the study, the engineers demonstrate a 3-by-3 grid of compartments that allow magnetic beads to enter but not leave. By tagging cells with magnetic particles and directing them to different compartments, the cells can be separated, sorted, stored, studied and retrieved.

In a random access memory chip, similar logic circuits manipulate electrons on a nanometer scale, controlling billions of compartments in a square inch. But cells are much larger than electrons, which would limit the new devices to hundreds of thousands of storage spaces per square inch.

But Yellen and Kim say that's still plenty small for their purposes.

"You need to analyze thousands of cells to get the statistics necessary to understand which genes are being turned on and off in response to pharmaceuticals or other stimuli," said Yellen. "And if you're looking for cells exhibiting rare behavior, which might be one cell out of a thousand, then you need arrays that can control hundreds of thousands of cells."

As an example, Yellen points to cells afflicted by HIV or cancer. In both diseases, most afflicted cells are active and can be targeted by therapeutics. A few rare cells, however, remain dormant, biding their time and avoiding destruction before activating and bringing the disease out of remission. With the new technology, the researchers hope to watch millions of individual cells, pick out the few that become dormant, quickly retrieve them and analyze their genetic activity.

"Maybe then we could find a way to target the dormant cells," said Yellen.

Kim added, "Our technology can offer new tools to improve our basic understanding of cancer metastasis at the single cell level, how cancer cells respond to chemical and physical stimuli, and to test new concepts for gene delivery and metabolite transfer during cell division and growth."

The researchers now plan to demonstrate a larger grid of 8-by-8 or 16-by-16 compartments with cells, and then to scale it up to hundreds of thousands of compartments. If successful, their technology would lend itself well to manufacturing, giving scientists around the world access to single-cell experimentation.

"Our idea is a simple one," said Kim. "Because it is a system similar to electronics and is based on the same technology, it would be easy to fabricate. That makes the system relevant to commercialization."

"There's another technique paper we need to do as a follow-up before we get to actual biological applications," added Yellen. "But they're on their way."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (CMMI-0800173), and the Research Triangle Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-1121107) and the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2013R1A1A2065222).

"Magnetophoretic circuits for digital control of single particles and cells," Byeonghwa Lim, Venu Reddy, XingHao Hu, KunWoo Kim, Mital Jadhav, Roozbeh Abedini-Nassab, Young-Woock Noh, Yong Taik Lim, Benjamin B. Yellen, CheolGi Kim. Nature Communications, 2014. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4846

Microchip-like technology allows single-cell analysis

Using components similar those that control electrons in microchips, researchers have designed a new device that can sort, store and retrieve individual cells for study

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using nature as a model for low-friction bearings

2014-05-14

Lubricants are required wherever moving parts come together. They prevent direct contact between solid elements and ensure that gears, bearings, and valves work as smoothly as possible. Depending on the application, the ideal lubricant must meet conflicting requirements. On the one hand, it should be as thin as possible because this reduces friction. On the other hand, it should be viscous enough that the lubricant stays in the contact gap. In practice, grease and oils are often used because their viscosity increases with pressure.

Biological lubrication in contrast is ...

Early menopause ups heart failure risk, especially for smokers

2014-05-14

CLEVELAND, Ohio (May 14, 2014)—Women who go through menopause early—at ages 40 to 45—have a higher rate of heart failure, according to a new study published online today in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). Smoking, current or past, raises the rate even more.

Research already pointed to a relationship between early menopause and heart disease—usually atherosclerotic heart disease. But this study from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, is the first to demonstrate a link with heart failure, the inability of the heart to pump ...

Virginia Tech updates football helmet ratings, 5 new helmets meet 5-star mark

2014-05-14

Virginia Tech has updated results of its adult football helmet ratings, which are designed to identify key differences between the abilities of individual helmets to reduce the risk of concussion.

All five of the new adult football helmets introduced this spring earned the five-star mark, which is the highest rating awarded by the Virginia Tech Helmet Ratings™. The complete ratings of the helmets manufactured by Schutt Sports and Xentih LLC, each with two new products, and Rawlings Sporting Goods Co., with one helmet, are publicly available at the helmet ratings website.

The ...

Primates and patience -- the evolutionary roots of self control

2014-05-14

Lincoln, Neb., May 14, 2014 – A chimpanzee will wait more than two minutes to eat six grapes, but a black lemur would rather eat two grapes now than wait any longer than 15 seconds for a bigger serving.

It's an echo of the dilemma human beings face with a long line at a posh restaurant. How long are they willing to wait for the five-star meal? Or do they head to a greasy spoon to eat sooner?

A paper published today in the scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B explores the evolutionary reasons why some primate species wait for a ...

Human learning altered by electrical stimulation of dopamine neurons

2014-05-14

PHILADELPHIA - Stimulation of a certain population of neurons within the brain can alter the learning process, according to a team of neuroscientists and neurosurgeons at the University of Pennsylvania. A report in the Journal of Neuroscience describes for the first time that human learning can be modified by stimulation of dopamine-containing neurons in a deep brain structure known as the substantia nigra. Researchers suggest that the stimulation may have altered learning by biasing individuals to repeat physical actions that resulted in reward.

"Stimulating the substantia ...

Hospital rankings for heart failure readmissions unaffected by patient's socioeconomic status

2014-05-13

A new report by Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, published in the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, shows the socioeconomic status of congestive heart failure patients does not influence hospital rankings for heart failure readmissions.

In the study, researchers assessed whether adding a standard measure for indicating the socioeconomic status of heart failure patients could alter the expected 30-day heart failure hospital risk standardized readmission rate (RSRR) among New York City hospitals. For each patient a standard socioeconomic ...

Medications can help adults with alcohol use disorders reduce drinking

2014-05-13

Several medications can help people with alcohol use disorders maintain abstinence or reduce drinking, according to research from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The work, published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), provides additional options for clinicians to effectively address this global concern.

Although alcohol use disorders are associated with many health problems, including cancers, stroke and depression, fewer than one-third of people with the ...

Clean air in Iowa

2014-05-13

With warmer weather, it's time to get outdoors. And now you can breathe easy about it: A new study from the University of Iowa reports Iowa's air quality falls within government guidelines for cleanliness.

The UI researchers analyzed air quality and pollution data compiled by state and county agencies over nearly three years at five sites spread statewide—urban areas Cedar Rapids, Davenport and Des Moines and rural locations in Montgomery county in southwest Iowa and Van Buren county in the southeast. The result: The air, as measured by a class of fine particulate pollutants ...

Scientists reveal structural secrets of enzyme used to make popular anti-cholesterol drug

2014-05-13

In pharmaceutical production, identifying enzyme catalysts that help improve the speed and efficiency of the process can be a major boon. Figuring out exactly why a particular enzyme works so well is an altogether different quest.

Take the cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin. First marketed commercially as Zocor, the statin drug has generated billions of dollars in annual sales. In 2011, UCLA scientists and colleagues discovered that a mutated enzyme could help produce the much sought-after pharmaceutical far more efficiently than the chemical process that had been ...

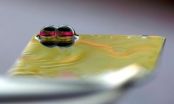

Novel ORNL technique enables air-stable water droplet networks

2014-05-13

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., May 13, 2014 -- A simple new technique to form interlocking beads of water in ambient conditions could prove valuable for applications in biological sensing, membrane research and harvesting water from fog.

Researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have developed a method to create air-stable water droplet networks known as droplet interface bilayers. These interconnected water droplets have many roles in biological research because their interfaces simulate cell membranes. Cumbersome fabrication methods, however, have limited ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

A depression treatment that once took eight weeks may work just as well in one

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

[Press-News.org] Microchip-like technology allows single-cell analysisUsing components similar those that control electrons in microchips, researchers have designed a new device that can sort, store and retrieve individual cells for study