Strongly interacting electrons in wacky oxide synchronize to work like the brain

2014-05-14

(Press-News.org) Current computing is based on binary logic -- zeroes and ones -- also called Boolean computing, but a new type of computing architecture stores information in the frequencies and phases of periodic signals and could work more like the human brain using a fraction of the energy necessary for today's computers, according to a team of engineers.

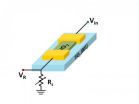

Vanadium dioxide is called a "wacky oxide" because it transitions from a conducting metal to an insulating semiconductor and vice versa with the addition of a small amount of heat or electrical current. A device created by electrical engineers at Penn State uses a thin film of vanadium oxide on a titanium dioxide substrate to create an oscillating switch.

Using a standard electrical engineering trick, Nikhil Shukla, graduate student in electrical engineering, added a series resistor to the oxide device to stabilize oscillations over billions of cycles. When Shukla added a second similar oscillating system, he discovered that, over time, the two devices began to oscillate in unison. This coupled system could provide the basis for non-Boolean computing. Shukla worked with Suman Datta, professor of electrical engineering, and co-advisor Roman Engel-Herbert, assistant professor of materials science and engineering, Penn State. They reported their results today (May 14) in Scientific Reports.

"It's called a small-world network," explained Shukla. "You see it in lots of biological systems, such as certain species of fireflies. The males will flash randomly, but then for some unknown reason the flashes synchronize over time."

The brain is also a small-world network of closely clustered nodes that evolved for more efficient information processing.

"Biological synchronization is everywhere," added Datta. "We wanted to use it for a different kind of computing called associative processing, which is an analog rather than digital way to compute."

An array of oscillators can store patterns -- for instance, the color of someone's hair, their height and skin texture. If a second area of oscillators has the same pattern, they will begin to synchronize, and the degree of match can be read out.

"They are doing this sort of thing already digitally, but it consumes tons of energy and lots of transistors," Datta said.

Datta is collaborating with Vijay Narayanan, professor of computer science and engineering, Penn State, in exploring the use of these coupled oscillations to solve visual recognition problems more efficiently than existing embedded vision processors.

Shukla and Datta called on the expertise of Cornell University materials scientist Darrell Schlom to make the vanadium dioxide thin film, which has extremely high quality similar to single crystal silicon. Arijit Raychowdhury, computer engineer, and Abhinav Parihar graduate student, both of Georgia Tech, mathematically simulated the nonlinear dynamics of coupled phase transitions in the vanadium dioxide devices. Parihar created a short video simulation of the transitions, which occur at a rate close to a million times per second, to show the way the oscillations synchronize. Venkatraman Gopalan, professor of materials science and engineering, Penn State, used the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory to visually characterize the structural changes occurring in the oxide thin film in the midst of the oscillations.

Datta believes it will take seven to 10 years to scale up from their current network of two-three coupled oscillators to the 100 million or so closely packed oscillators required to make a neuromorphic computer chip. One of the benefits of the novel device is that it will use only about one percent of the energy of digital computing, allowing for new ways to design computers. Much work remains to determine if vanadium dioxide can be integrated into current silicon wafer technology.

"It's a fundamental building block for a different computing paradigm that is analog rather than digital," said Shukla.

INFORMATION:

Also contributing to this work are Eugene Freeman and Greg Stone, all of Penn State; Haidan Wen and Zhonghou Cai, Argonne National Laboratory; and Hanjong Paik, Cornell University.

The Office of Naval Research primarily supported this work. The National Science Foundation's Expeditions in Computing Award also supported this work.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research shows hope for normal heart function in children with fatal heart disease

2014-05-14

DETROIT, Mich., - After two decades of arduous research, a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded investigator at the Children's Hospital of Michigan (CHM) at the Detroit Medical Center (DMC) and the Wayne State University School of Medicine has published a new study showing that many children with an often fatal type of heart disease can recover "normal size and function" of damaged sections of their hearts.

The finding by Children's Hospital of Michigan's Pediatrician-in-Chief and Wayne State University Chair of Pediatrics Steven E. Lipshultz, M.D., F.A.A.P., F.A.H.A., ...

Study finds free fitness center-based exercise referral program not well utilized

2014-05-14

Eliminating financial barriers to a fitness center as well as providing physician support, a pleasant environment and trained fitness staff did not result in widespread membership activation or consistent attendance among low income, multi-ethnic women with chronic disease risk factors or diagnoses according to a new study from Boston University School of Medicine. The findings, published in Journal of Community Health, is believed to be the first study of its kind to examine patient characteristics associated with utilization of community health center- based exercise ...

Study finds outcome data in clinical trials reported inadequately, inconsistently

2014-05-14

Philadelphia, May 14, 2014 – There is increasing public pressure to report the results of all clinical trials to eliminate publication bias and improve public access. However, investigators using the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) to build a database of clinical trials involving chronic pain have encountered several challenges. They describe the perils and pitfalls of using the ICTRP and propose alternative strategies to improve clinical trials reporting. This important and insightful study is published in the August ...

Enzyme helps stem cells improve recovery from limb injuries

2014-05-14

AUGUSTA, Ga. – While it seems like restoring blood flow to an injured leg would be a good thing, it can actually cause additional damage that hinders recovery, researchers say.

Ischemia reperfusion injury affects nearly two million Americans annually with a wide variety of scenarios that temporarily impede blood flow – from traumatic limb injuries, to heart attacks, to donor organs, said Dr. Babak Baban, immunologist at the Medical College of Georgia and College of Dental Medicine at Georgia Regents University.

Restoring blood flow actually heightens inflammation ...

By itself, abundant shale gas unlikely to alter climate projections

2014-05-14

DURHAM, N.C. -- While natural gas can reduce greenhouse emissions when it is substituted for higher-emission energy sources, abundant shale gas is not likely to substantially alter total emissions without policies targeted at greenhouse gas reduction, a pair of Duke researchers find.

If natural gas is abundant and less expensive, it will encourage greater natural gas consumption and less of fuels such as coal, renewables and nuclear power. The net effect on the climate will depend on whether the greenhouse emissions from natural gas -- including carbon dioxide and methane ...

New smart coating could make oil-spill cleanup faster and more efficient

2014-05-14

In the wake of recent off-shore oil spills, and with the growing popularity of "fracking" — in which water is used to release oil and gas from shale — there's a need for easy, quick ways to separate oil and water. Now, scientists have developed coatings that can do just that. Their report on the materials, which also could stop surfaces from getting foggy and dirty, appears in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

J.P.S. Badyal and colleagues point out that oil-spill cleanup crews often use absorbents, like clays, straw and wool to sop up oil, but these materials aren't ...

Advance brings 'hyperbolic metamaterials' closer to reality

2014-05-14

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers have taken a step toward practical applications for "hyperbolic metamaterials," ultra-thin crystalline films that could bring optical advances including powerful microscopes, quantum computers and high-performance solar cells.

New developments are reminiscent of advances that ushered in silicon chip technology, said Alexandra Boltasseva, a Purdue University associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

Optical metamaterials harness clouds of electrons called surface plasmons to manipulate and control light. However, some ...

New efforts aim to shore up forensic science -- but will they work?

2014-05-14

Five years ago, a report on the state of forensic science by the National Academy of Sciences decried the lack of sound science in the analysis of evidence in criminal cases across the country. It spurred a flurry of outrage and promises, but no immediate action. Now, renewed efforts are underway, according to an article in Chemical & Engineering News, the weekly news magazine of the American Chemical Society.

C&EN editors Andrea Widener and Carmen Drahl note that the 2009 report served as a critical wake-up call to the public, defense attorneys and policymakers. Even ...

Building a longer-lasting, high-capacity electric car battery from sulfur -- video

2014-05-14

WASHINGTON, May 13, 2014 — A new prototype electric car battery could take you a lot farther and last a lot longer. Jeff Pyun, Ph.D., and his team at the University of Arizona are using modified sulfur, a common industrial waste product, to boost the charge capacity and extend the life of these batteries. Their work could also drastically reduce the price of electric car batteries, some of which currently cost more than $10,000 to replace. In the American Chemical Society's (ACS') newest Breakthrough Science video, Pyun and graduate student Jared Griebel explain the technology ...

Bioethics commission plays early role in BRAIN Initiative

2014-05-14

Washington, DC— Calling for the integration of ethics across the life of neuroscientific research endeavors, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues (Bioethics Commission) released volume one of its two-part response to President Obama's request related to the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. The report, Gray Matters: Integrative Approaches for Neuroscience, Ethics, and Society, includes four recommendations for institutions and individuals engaged in neuroscience research including government agencies ...