(Press-News.org) The gene mutations driving cancer have been tracked for the first time in patients back to a distinct set of cells at the root of cancer – cancer stem cells.

The international research team, led by scientists at the University of Oxford and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, studied a group of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes – a malignant blood condition which frequently develops into acute myeloid leukaemia.

The researchers say their findings, reported in the journal Cancer Cell, offer conclusive evidence for the existence of cancer stem cells.

The concept of cancer stem cells has been a compelling but controversial idea for many years. It suggests that at the root of any cancer there is a small subset of cancer cells that are solely responsible for driving the growth and evolution of a patient's cancer. These cancer stem cells replenish themselves and produce the other types of cancer cells, as normal stem cells produce other normal tissues.

The concept is important, because it suggests that only by developing treatments that get rid of the cancer stem cells will you be able to eradicate the cancer. Likewise, if you could selectively eliminate these cancer stem cells, the other remaining cancer cells would not be able to sustain the cancer.

'It's like having dandelions in your lawn. You can pull out as many as you want, but if you don't get the roots they'll come back,' explains first author Dr Petter Woll of the MRC Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine at the University of Oxford.

The researchers, led by Professor Sten Eirik W Jacobsen at the MRC Molecular Haematology Unit and the Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine at the University of Oxford, investigated malignant cells in the bone marrow of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and followed them over time.

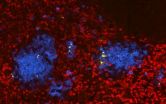

Using genetic tools to establish in which cells cancer-driving mutations originated and then propagated into other cancer cells, they demonstrated that a distinct and rare subset of MDS cells showed all the hallmarks of cancer stem cells, and that no other malignant MDS cells were able to propagate the tumour.

The MDS stem cells were rare, sat at the top of a hierarchy of MDS cells, could sustain themselves, replenish the other MDS cells, and were the origin of all stable DNA changes and mutations that drove the progression of the disease.

'This is conclusive evidence for the existence of cancer stem cells in myelodysplastic syndromes,' says Dr Woll. 'We have identified a subset of cancer cells, shown that these rare cells are invariably the cells in which the cancer originates, and also are the only cancer-propagating cells in the patients. It is a vitally important step because it suggests that if you want to cure patients, you would need to target and remove these cells at the root of the cancer – but that would be sufficient, that would do it.'

The existence of cancer stem cells has already been reported in a number of human cancers, explains Professor Jacobsen, but previous findings have remained controversial since the lab tests used to establish the identity of cancer stem cells have been shown to be unreliable and, in any case, do not reflect the "real situation" in an intact tumour in a patient.

'In our studies we avoided the problem of unreliable lab tests by tracking the origin and development of cancer-driving mutations in MDS patients,' says Professor Jacobsen, who also holds a guest professorship at the Karolinska Institutet.

Dr Woll adds: 'We can't offer patients today new treatments with this knowledge. What it does is give us a target for development of more efficient and cancer stem cell specific therapies to eliminate the cancer.

'We need to understand more about what makes these cancer stem cells unique, what makes them different to all the other cancer cells. If we can find biological pathways that are specifically dysregulated in cancer stem cells, we might be able to target them with new drugs.'

Dr Woll cautions: 'It is important to emphasize that our studies only investigated cancer stem cells in MDS, and that the identity, number and function of stem cells in other cancers are likely to differ from that of MDS.'

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Notes to Editors

The researchers looked at bone marrow cells from 15 low or intermediate risk MDS patients – those that were least likely to progress to leukaemia (although the risk is still very high). The condition was followed in detail over time for four of these patients; one for two years, two for 30 months and one for a total of 10 years.

The existence of cancer stem cells in studies in mice was established in three papers published in the journals Nature and Science on the same day in August 2012.

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a malignant blood disorder that causes a drop in the number of healthy red and white blood cells as well as platelets, causing serious symptoms including weakness, tiredness and occasional breathlessness, and frequent infections and bleeding. Half of MDS patients go on to develop acute myeloid leukemia. It is most common in people aged 65-70 years. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/myelodysplasia/Pages/Introduction.aspx

The paper 'Myelodysplastic syndromes are propagated by rare and distinct human cancer stem cells in vivo' by Petter Woll and colleagues is to be published in the journal Cancer Cell with an embargo of 17:00 UK time / 12noon US Eastern time on Thursday 15 May 2014.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is funded by the Department of Health to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research. Since its establishment in April 2006, the NIHR has transformed research in the NHS. It has increased the volume of applied health research for the benefit of patients and the public, driven faster translation of basic science discoveries into tangible benefits for patients and the economy, and developed and supported the people who conduct and contribute to applied health research. The NIHR plays a key role in the Government's strategy for economic growth, attracting investment by the life-sciences industries through its world-class infrastructure for health research. Together, the NIHR people, programmes, centres of excellence and systems represent the most integrated health research system in the world. For further information, visit the NIHR website.

Oxford University's Medical Sciences Division is one of the largest biomedical research centres in Europe, with over 2,500 people involved in research and more than 2,800 students. The University is rated the best in the world for medicine, and it is home to the UK's top-ranked medical school.

From the genetic and molecular basis of disease to the latest advances in neuroscience, Oxford is at the forefront of medical research. It has one of the largest clinical trial portfolios in the UK and great expertise in taking discoveries from the lab into the clinic. Partnerships with the local NHS Trusts enable patients to benefit from close links between medical research and healthcare delivery.

A great strength of Oxford medicine is its long-standing network of clinical research units in Asia and Africa, enabling world-leading research on the most pressing global health challenges such as malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS and flu. Oxford is also renowned for its large-scale studies which examine the role of factors such as smoking, alcohol and diet on cancer, heart disease and other conditions.

Genetic tracking identifies cancer stem cells in human patients

2014-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Combination therapy a potential strategy for treating Niemann Pick disease

2014-05-15

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (May 15, 2014) – By studying nerve and liver cells grown from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), Whitehead Institute researchers have identified a potential dual-pronged approach to treating Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease, a rare but devastating genetic disorder.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), approximately 1 in 150,000 children born are afflicted with NPC, the most common variant of Niemann-Pick. Children with NPC experience abnormal accumulation of cholesterol in their liver and nerve cells, leading to ...

'Bystander' chronic infections thwart development of immune cell memory

2014-05-15

PHILADELPHIA – Studies of vaccine programs in the developing world have revealed that individuals with chronic infections such as malaria and hepatitis tend to be less likely to develop the fullest possible immunity benefits from vaccines for unrelated illnesses. The underlying mechanisms for that impairment, however, are unclear, and distinguishing these so-called "bystander" effects on priming the immune system to fight future assaults versus development of immunological memory has been challenging.

A team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania ...

E-cigarette awareness goes up, as (apparently) so does skepticism

2014-05-15

PHILADELPHIA (May 15, 2014) – Americans are unquestionably more aware of e-cigarettes, those vapor-emitting alternatives to tobacco cigarettes, according to a national survey. Yet, at the same time, the belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional smokes may be starting to diminish.

A national survey of 3,630 adults found that 77 percent of the respondents have heard of e-cigarettes; that's way up from 16 percent just five years ago. But the perception that e-cigarettes are actually less harmful than tobacco cigarettes among current smokers decreased slightly, ...

Protein sharpens salmonella needle for attack

2014-05-15

A tiny nanoscale syringe is Salmonella's weapon. Using this, the pathogen injects its molecular agents into the host cells and manipulates them to its own advantage. A team of scientists at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel demonstrate in their current publication in Cell Reports that a much investigated protein, which plays a role in Salmonella metabolism, is required to activate these needles and makes the replication and spread of Salmonella throughout the whole body possible.

The summer months are the prime time for Salmonella infections. Such an infection ...

The color of blood: Pigment helps stage symbiosis in squid

2014-05-15

MADISON, Wis. – The small but charismatic Hawaiian bobtail squid is known for its predator-fooling light organ.

To survive, the nocturnal cephalopod depends on a symbiotic association with a luminescent bacterium that gives it the ability to mimic moonlight on the surface of the ocean and, in the fashion of a Klingon cloaking device, deceive barracuda and other fish that would happily make a meal of the small creature.

The relationship between the squid and the bacterium Vibrio fischeri is well chronicled, but writing in the current issue of the journal Proceedings ...

Synthetic biology still in uncharted waters of public opinion

2014-05-15

The Synthetic Biology Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars is releasing the results of a new set of focus groups, which find continued low awareness of synthetic biology among the general public.

The focus groups also sought opinions on the emerging field of neural engineering.

The focus group results support the findings of a quantitative national poll conducted by Hart Research Associates in January 2013, which found just 23 percent of respondents reported they had heard a lot (6 percent) or some (17 percent) about synthetic biology.

The ...

Added benefit of the fixed combination of dapagliflozin and metformin is not proven

2014-05-15

The fixed combination of the drugs dapagliflozin and metformin (trade name: Xigduo) has been approved since January 2014 for adults with type 2 diabetes in whom diet and exercise do not provide adequate glycaemic control. In an early benefit assessment pursuant to the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medicinal Products (AMNOG), the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) now examined whether this new drug combination offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy. No such added benefit can be derived from the dossier, however, ...

Mothers' symptoms of depression predict how they respond to child behavior

2014-05-15

Depressive symptoms seem to focus mothers' responses on minimizing their own distress, which may come at the expense of focusing on the impact their responses have on their children, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Depressive symptoms are common among mothers, and these symptoms are linked with worse developmental outcomes for children. The new study, which followed 319 mothers and their children over a two-year period, helps to explain why parenting competence seems to deteriorate as parents' ...

Justifying wartime atrocities alters memories

2014-05-15

PRINCETON, N.J.—Stories about wartime atrocities and torture methods, like waterboarding and beatings, often include justifications – despite whether the rationale is legitimate.

Now, a study by Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School shows how those justifications actually creep into people's memories of war, excusing the actions of their side. The researchers report in Psychological Science shows how Americans' motivation to remember information that absolves American soldiers of atrocities alters their memories.

"People are motivated to remember information ...

Single episode of binge drinking can adversely affect health according to new UMMS study

2014-05-15

WORCESTER, MA – It only takes one time. That's the message of a new study by scientists at the University of Massachusetts Medical School on binge drinking. Their research found that a single episode of binge drinking can have significant negative health effects resulting in bacteria leaking from the gut, leading to increased levels of toxins in the blood. Published online in PLOS ONE, the study showed that these bacterial toxins, called endotoxins, caused the body to produce immune cells involved in fever, inflammation, and tissue destruction.

"We found that a single ...