(Press-News.org) In a basement lab on BYU's campus, mechanical engineering professor Julie Crockett analyzes water as it bounces like a ball and rolls down a ramp.

This phenomenon occurs because Crockett and her colleague Dan Maynes have created a sloped channel that is super-hydrophobic, or a surface that is extremely difficult to wet. In layman's terms, it's the most extreme form of water proof.

Engineers like Crockett and Maynes have spent decades studying super-hydrophobic surfaces because of the plethora of real-life applications. And while some of this research has resulted in commercial products that keep shoes dry or prevent oil from building up on bolts, the duo of BYU professors are uncovering characteristics aimed at large-scale solutions for society.

Their recent study on the subject, published in academic journal Physics of Fluids, finds surfaces with a pattern of microscopic ridges or posts, combined with a hydrophobic coating, produces an even higher level of water resistance--depending on how the water hits the surface.

"Our research is geared toward helping to create the ideal super-hydrophobic surface," Crockett said. "By characterizing the specific properties of these different surfaces, we can better pinpoint which types of surfaces are most advantageous for each application."

Their work is critical because the growing list of applications for super-hydrophobic surfaces is extremely diverse:

Solar panels that don't get dirty or can self-clean when water rolls off of them

Showers, tubs or toilets you don't want hard water spots to mark

Bio-medical devices, such as the interior of tubes or syringes that deliver fluids to patients

Hulls of ships, exterior of torpedoes or submarines

Airplane wings that will resist wingtip icing in cold humid conditions

But where Crockett and Maynes' research is really headed is toward cleaner and more efficient energy generation. Nearly every power plant across the country creates energy by burning coal or natural gas to create steam that expands and rotates a turbine. Once that has happened, the steam needs to be condensed back into a liquid state to be cycled back through.

If power plant condensers can be built with optimal super-hydrophobic surfaces, that process can be sped up in significant ways, saving time and lowering costs to generate power.

"If you have these surfaces, the fluid isn't attracted to the condenser wall, and as soon as the steam starts condensing to a liquid, it just rolls right off," Crockett said. "And so you can very, very quickly and efficiently condense a lot of gas."

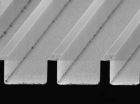

The super-hydrophobic surfaces the researchers are testing in the lab fall into one of two categories: surfaces with micro posts or surfaces with ribs and cavities one tenth the size of a human hair. (See images of each to the right.)

To create these micro-structured surfaces, the professors use a process similar to photo film development that etches patterns onto CD-sized wafers. The researchers then add a thin water-resistant film to the surfaces, such as Teflon, and use ultra-high-speed cameras to document the way water interacts when dropped, jetted or boiled on them.

They're finding slight alterations in the width of the ribs and cavities, or the angles of the rib walls are significantly changing the water responses. All of this examination is providing a clearer picture of why super-hydrophobic surfaces do what they do.

"People know about these surfaces, but why they cause droplets or jets to behave the way they do is not particularly well known," Crockett said. "If you don't know why the phenomena are occurring, it may or may not actually be beneficial to you."

INFORMATION: END

Professors' super waterproof surfaces cause water to bounce like a ball

BYU research on super-hydrophobic surfaces could result in cleaner, more efficient power

2014-05-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Termite genome lays roadmap for 'greener' control measures

2014-05-20

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - A team of international researchers has sequenced the genome of the Nevada dampwood termite, providing an inside look into the biology of the social insect and uncovering new genetic targets for pest control.

Michael Scharf, a Purdue University professor of entomology who participated in the collaborative study, said the genome could help researchers develop control strategies that are more specific than the broad-spectrum chemicals conventionally used to treat termite infestations.

"The termite genome reveals many unique genetic targets that can ...

Fairy circles apparently not created by termites after all

2014-05-20

This news release is available in German. Leipzig. For several decades scientists have been trying to come up with an explanation for the formation of the enigmatic, vegetation-free circles frequently found in certain African grassland regions. Now researchers have tested different prevailing hypotheses as to their respective plausibility. For the first time they have carried out a detailed analysis of the spatial distribution of these fairy circles – and discovered a remarkably regular and spatially comprehensive homogenous distribution pattern. This may best be explained ...

Fossils prove useful in analyzing million year old cyclical phenomena

2014-05-20

Research conducted at the University of Granada has shown that the cyclical phenomena that affect the environment, like climate change, in the atmosphere-ocean dynamic and, even, disturbances to planetary orbits, have existed since hundreds of millions of year ago and can be studied by analysing fossils.

This is borne out by the palaeontological data analysed, which have facilitated the characterization of irregular cyclical paleoenvironmental changes, lasting between less than 1 day and up to millions of years.

Francisco J. Rodríguez-Tovar, Professor de Stratigraphy ...

Improved computer simulations enable better calculation of interfacial tension

2014-05-20

Computer simulations play an increasingly important role in the description and development of new materials. Yet, despite major advances in computer technology, the simulations in statistical physics are typically restricted to systems of up to a few 100,000 particles, which is many times smaller than the actual material quantities used in typical experiments. Researchers therefore use so-called finite-size corrections in order to adjust the results obtained for comparatively small simulation systems to the macroscopic scale. A team of researchers from Johannes Gutenberg ...

Particles near absolute zero do not break the laws of physics after all

2014-05-20

In theory, the laws of physics are absolute. However, when it comes to the laws of thermodynamics—the science that studies how heat and temperature relate to energy—there are times where they no longer seem to apply. In a paper recently published in EPJ B, Robert Adamietz from the University of Augsburg, Germany, and colleagues have demonstrated that a theoretical model of the environment's influence on a particle does not violate the third law of thermodynamics, despite appearances to the contrary. These findings are relevant for systems at the micro or nanometer scale ...

Busting rust with light: New technique safely penetrates top coat for perfect paint job

2014-05-20

WASHINGTON, May 20, 2014 – To keep your new car looking sleek and shiny for years, factories need to make certain that the coats of paint on it are applied properly. But ensuring that every coat of paint—whether it is on a car or anything else—is of uniform thickness and quality is not easy.

Now researchers have developed a new way to measure the thickness of paint layers and the size of particles embedded inside. Unlike conventional methods, the paint remains undamaged, making the technique useful for a variety of applications from cars to artifacts, cancer detection ...

Pine bark substance could be potent melanoma drug

2014-05-20

A substance that comes from pine bark is a potential source for a new treatment of melanoma, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers.

Current melanoma drugs targeting single proteins can initially be effective, but resistance develops relatively quickly and the disease recurs. In those instances, resistance usually develops when the cancer cell's circuitry bypasses the protein that the drug acts on, or when the cell uses other pathways to avoid the point on which the drug acts.

"To a cancer cell, resistance is like a traffic problem in its circuitry," ...

Flu vaccines in schools limited by insurer reimbursement

2014-05-20

AURORA, Colo. (May 20, 2014) – School-based influenza vaccine programs have the potential to reach many children at affordable costs and with parental support, but these programs are limited by low rates of reimbursement from third-party payers, according to recently published study results by researchers from the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

A school-based flu vaccine program in the Denver Public Schools was effective at reaching nearly one-third of the students, but billing and reimbursement issues posed significant problems for administrators of the program.

"The ...

Study shows how streptococcal bacteria can be used to fight colon cancer

2014-05-20

Researchers at Western University (London, Canada) have shown how the bacteria primarily responsible for causing strep throat can be used to fight colon cancer. By engineering a streptococcal bacterial toxin to attach itself to tumour cells, they are forcing the immune system to recognize and attack the cancer.

Kelcey Patterson, a PhD Candidate at Western and the lead author on the study, showed that the engineered bacterial toxin could significantly reduce the size of human colon cancer tumours in mice, with a drastic reduction in the instances of metastasis. By using ...

Parents of overweight kids more likely to give schools failing grades for fighting obesity

2014-05-20

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Parents – especially those of overweight children – give schools a failing grade for efforts to encourage healthy habits that combat childhood obesity, according to a new poll from the University of Michigan.

According to the latest University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health, parents with at least one overweight child (25 percent of all parents in the poll) were more likely to give schools a failing grade of D or F for obesity-related efforts than parents of normal-weight children.

Parents of overweight ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

[Press-News.org] Professors' super waterproof surfaces cause water to bounce like a ballBYU research on super-hydrophobic surfaces could result in cleaner, more efficient power