(Press-News.org) Researchers at King's College London have discovered how a molecular 'scaffold' which allows key parts of cells to interact, comes apart in dementia and motor neuron disease, revealing a potential new target for drug discovery.

The study, published today in Nature Communications, was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, Alzheimer's Research UK and the Motor Neurone Disease Association.

Researchers looked at two components of cells: mitochondria, the cell 'power houses' which produce energy for the cell; and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) which makes proteins and stores calcium for signalling processes in the cell. ER and mitochondria form close associations and these interactions enable a number of important cell functions. However the mechanism by which ER and mitochondria become linked has not, until now, been fully understood.

Professor Chris Miller, from the Institute of Psychiatry at King's and lead author of the paper, says: "At the molecular level, many processes go wrong in dementia and motor neuron disease, and one of the puzzles we're faced with is whether there is a common pathway connecting these different processes. Our study suggests that the loosening of this 'scaffold' between the mitochondria and ER in the cell may be a key process in neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia or motor neuron disease."

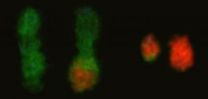

By studying cells in a dish, the researchers discovered that an ER protein called VAPB binds to a mitochondrial protein called PTPIP51, to form a 'scaffold' enabling ER and mitochondria to form close associations. In fact, by increasing the levels of VAPB and PTPIP51, mitochondria and ER re-organised themselves to form tighter bonds.

Many of the cell's functions that are controlled by ER-mitochondria associations are disrupted in neurodegenerative diseases, so the researchers studied how the strength of this 'scaffold' was affected in these diseases. TPD-43 is a protein which is strongly linked to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, a form of motor neuron disease) and Fronto-Temporal Dementia (FTD, the second most common form of dementia), but exactly how the protein causes neurodegeneration is not properly understood.

The researchers studied how TPD-43 affected mouse cells in a dish. They found that higher levels of TPD-43 resulted in a loosening of the scaffold which reduced ER-mitochondria bonds, affecting some important cellular functions that are linked to ALS and FTD.

Professor Miller concludes: "Our findings are important in terms of advancing our understanding of basic biology, but may also provide a potential new target for developing new treatments for these devastating disorders."

INFORMATION:

For a copy of the paper, or interview with the author, please contact Seil Collins, Press Officer, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London seil.collins@kcl.ac.uk / (+44) 0207 848 5377 / (+44) 07718 697 176

Paper reference: Stoica, R. et al. 'ER-mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTP-associated TDP-43' published in Nature Communications

About King's College London

King's College London is one of the top 20 universities in the world (2013/14 QS World University Rankings) and the fourth oldest in England. It is The Sunday Times 'Best University for Graduate Employment 2012/13'. A research-led university based in the heart of London, King's has more than 25,000 students (of whom more than 10,000 are graduate students) from nearly 140 countries, and more than 6,500 employees. King's is in the second phase of a £1 billion redevelopment programme which is transforming its estate.

King's has an outstanding reputation for providing world-class teaching and cutting-edge research. In the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise for British universities, 23 departments were ranked in the top quartile of British universities; over half of our academic staff work in departments that are in the top 10 per cent in the UK in their field and can thus be classed as world leading. The College is in the top seven UK universities for research earnings and has an overall annual income of nearly £554 million.

King's has a particularly distinguished reputation in the humanities, law, the sciences (including a wide range of health areas such as psychiatry, medicine, nursing and dentistry) and social sciences including international affairs. It has played a major role in many of the advances that have shaped modern life, such as the discovery of the structure of DNA and research that led to the development of radio, television, mobile phones and radar.

King's College London and Guy's and St Thomas', King's College Hospital and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trusts are part of King's Health Partners. King's Health Partners Academic Health Sciences Centre (AHSC) is a pioneering global collaboration between one of the world's leading research-led universities and three of London's most successful NHS Foundation Trusts, including leading teaching hospitals and comprehensive mental health services. For more information, visit: http://www.kingshealthpartners.org.

The College is in the midst of a five-year, £500 million fundraising campaign – World questions|King's answers – created to address some of the most pressing challenges facing humanity as quickly as feasible. The campaign's five priority areas are neuroscience and mental health, leadership and society, cancer, global power and children's health. More information about the campaign is available at http://www.kcl.ac.uk/kingsanswers.

Molecular 'scaffold' could hold key to new dementia treatments

Researchers at King's College London have discovered how a molecular 'scaffold' which allows key parts of cells to interact, comes apart in dementia and motor neuron disease, revealing a potential new target for drug discovery

2014-06-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Controlling thermal conductivities can improve energy storage

2014-06-03

Controlling the flow of heat through materials is important for many technologies. While materials with high and low thermal conductivities are available, materials with variable and reversible thermal conductivities are rare, and other than high pressure experiments, only small reversible modulations in thermal conductivities have been reported.

For the first time, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have experimentally shown that the thermal conductivity of lithium cobalt oxide (LixCoO2), an important material for electrochemical energy storage, ...

Tumor chromosomal translocations reproduced for the first time in human cells

2014-06-03

Scientists from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) and the Spanish National Cardiovascular Research Centre (CNIC) have been able to reproduce, for the first time in human cells, chromosomal translocations associated with two types of cancer: acute myeloid leukaemia and Ewing's sarcoma. The discovery, published today in the journal Nature Communications, opens the door to the development of new therapeutic targets to fight these types of cancer.

The study was carried out by Sandra Rodriguez-Perales − from CNIO's Molecular Cytogenetics Group, led ...

Children with autism have elevated levels of steroid hormones in the womb

2014-06-03

Scientists from the University of Cambridge and the Statens Serum Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark have discovered that children who later develop autism are exposed to elevated levels of steroid hormones (for example testosterone, progesterone and cortisol) in the womb. The finding may help explain why autism is more common in males than females, but should not be used to screen for the condition.

Funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), the results are published today in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

The team, led by Professor Simon Baron-Cohen and Dr ...

Reduced neurosurgical resident hours: No significant positive effect on patient outcomes

2014-06-03

Charlottesville, VA (June 3, 2014). In July 2003 the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) imposed a mandatory maximum 80-hour work-week restriction on medical residents. Before that time residents often worked in excess of 100 hours per week. To investigate whether positive changes in patient outcomes occurred following implementation of the ACGME mandate, four researchers from Minnesota—Kiersten Norby, M.D., Farhan Siddiq, M.D., Malik M. Adil, M.D., and Stephen J. Haines, M.D.—analyzed hospital-based data from three years before (2000-2002) and ...

Survey finds 'significant gap' in detection of malnutrition in Canadian hospital patients

2014-06-03

A new survey of Canadian physicians shows a "significant gap" between optimal practices to detect nutrition problems in hospitalized patients and what action is actually taking place.

The survey, conducted by the Canadian Malnutrition Task Force, looked at physician attitudes and perceptions about identifying and treating nutrition issues among hospitalized patients. The startling findings of the survey were published today in the OnlineFirst version of the Journal of Parenteral and External Nutrition (JPEN), the research journal of the American Society for Parenteral ...

Bacterium causing US catfish deaths has Asian roots

2014-06-03

A bacterium causing an epidemic among catfish farms in the southeastern United States is closely related to organisms found in diseased grass carp in China, according to researchers at Auburn University in Alabama and three other institutions. The study, published this week in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, suggests that the virulent U.S. fish epidemic emerged from an Asian source.

Since 2009, catfish farming in Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas has been seriously impacted by an emerging strain of Aeromonas hydrophila, ...

New amyloid-reducing compound could be a preventive measure against Alzheimer's

2014-06-03

Scientists at NYU Langone Medical Center have identified a compound, called 2-PMAP, in animal studies that reduced by more than half levels of amyloid proteins in the brain associated with Alzheimer's disease. The researchers hope that someday a treatment based on the molecule could be used to ward off the neurodegenerative disease since it may be safe enough to be taken daily over many years.

"What we want in an Alzheimer's preventive is a drug that modestly lowers amyloid beta and is also safe for long term use," says Martin J. Sadowski, MD, PhD, associate professor ...

Screening has prevented half a million colorectal cancers

2014-06-03

New Haven, Conn. – An estimated half a million cancers were prevented by colorectal cancer screening in the United States from 1976 to 2009, report researchers from the Cancer Outcomes, Public Policy, and Effectiveness Research (COPPER) Center at Yale Cancer Center. Their study appears in the journal Cancer.

During this more than 30-year time span, as increasing numbers of men and women underwent cancer screening tests — including fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopies, and colonoscopies — colorectal cancer rates declined significantly, the researchers found.

The ...

Insect repellents more important than ever as tropical tourism increases

2014-06-03

Holidaymakers are being urged to use insect repellent to protect themselves against bites and the diseases they can spread, as trends show travel to tropical countries is rising among Britons.

With the World Cup starting in Brazil next week and holiday season about to get under way, scientists from repellent testing facility arctec at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine today launch Bug Off - the first ever Insect Repellent Awareness Day to highlight the issue.

They recommend applying repellents containing 20-50% DEET to the skin when in countries with ...

Left-handed fetuses could show effects of maternal stress on unborn babies

2014-06-03

Fetuses are more likely to show left-handed movements in the womb when their mothers are stressed, according to new research.

Researchers at Durham and Lancaster universities say their findings are an indicator that maternal stress could have a temporary effect on unborn babies, adding that their research highlights the importance of reducing stress during pregnancy.

However, the researchers emphasised that their study was not evidence that maternal stress led to fixed left-handedness in infants after birth. They said that some people might be genetically predisposed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

Adolescent and young adult requests for medication abortion through online telemedicine

Researchers want a better whiff of plant-based proteins

Pioneering a new generation of lithium battery cathode materials

A Pitt-Johnstown professor found syntax in the warbling duets of wild parrots

[Press-News.org] Molecular 'scaffold' could hold key to new dementia treatmentsResearchers at King's College London have discovered how a molecular 'scaffold' which allows key parts of cells to interact, comes apart in dementia and motor neuron disease, revealing a potential new target for drug discovery