(Press-News.org) One of the defining features of cells is their membranes. Each cell's repository of DNA and protein-making machinery must be kept stable and secure from invaders and toxins. Scientists have attempted to replicate these properties, but, despite decades of research, even the most basic membrane structures, known as vesicles, still face many problems when made in the lab. They are difficult to make at consistent sizes and lack the stability of their biological counterparts.

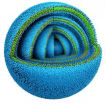

Now, University of Pennsylvania researchers have shown that a certain kind of dendrimer, a molecule that features tree-like branches, offers a simple way of creating vesicles and tailoring their diameter and thickness. Moreover, these dendrimer-based vesicles self-assemble with concentric layers of membranes, much like an onion.

By altering the concentration of the dendrimers suspended within, the researchers have shown that they can control the number of layers, and thus the diameter of the vesicle, when the solution is injected in water. Such a structure opens up possibilities of releasing drugs over longer periods of time, with a new dose in each layer, or even putting a cocktail of drugs in different layers so each is released in sequence.

The study was led by professor Virgil Percec, of the Department of Chemistry in Penn's School of Arts & Sciences. Also contributing to the study were members of Percec's lab, Shaodong Zhang, Hao-Jan Sun, Andrew D. Hughes, Ralph-Olivier Moussodia and Annabelle Bertin, as well as professor Paul Heiney of the Department of Physics and Astronomy. They collaborated with researchers at the University of Delaware and Temple University.

Their study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Cell membranes are made of two layers of molecules, each of which has a head that is attracted to water and a tail that is repelled by it. These bilayer membranes self-assemble so that the hydrophilic heads of the molecules of both layers are on the exterior, facing the water that is in the cell's environment as well as the water encapsulated inside.

For decades, scientists have been trying to replicate the most basic form of this arrangement, known as a vesicle, in the lab. Stripping out the additional proteins and sugars that cells naturally have in their membranes leaves just a double-walled bubble that can be stuffed with drugs or other useful content.

"The problem," Percec said, "is that once you remove the proteins and the other elements of a real biological membrane, they are unstable and don't last for a long time. It's also hard to control their permeability and their polydispersity, which is how close together in size they are. The methodologies for producing them are also complicated and expensive."

Research in this field has thus been focused on finding new chemistries to replace the fatty molecules that normally make up a vesicle's bilayer.

The Percec group's breakthrough came in 2010, when they started making vesicles using a class of molecules called amphiphilic Janus dendrimers.

Like the Roman god Janus, these molecules have two faces. Each face has tree-like branches instead of the head and tail found in the molecules that make up biological membranes found in nature. But like those molecules, these dendrimers are amphiphilic, meaning that one face's branches is hydrophilic and the other is hydrophobic.

In 2010, Percec and his colleagues found the smallest possible amphiphilic Janus dendrimer. Dissolving those molecules in an alcohol solution and injecting them into water, the researchers found that they formed stable, evenly sized vesicles.

Not all cells are content with just a single bilayer, however. Some biological systems, such as gram-negative bacteria and the myelin sheaths that cover nerves, have multiple concentric bilayers. Having a model system with that arrangement could provide some fundamental insights to these real-world systems, and the added stability of extra layers of padding would be a useful trait in clinical applications. However, methods for producing vesicles with multiple bilayers remained elusive.

"The only way it has been achieved in the past was through a complicated mechanical process, which was a dead end," Percec said. "This was not a viable option for mass-producing multilayered vesicles, but, with our library of amphiphilic Janus dendrimers, we were lucky to find some molecules that have in their chemicals instructions needed to self-assemble into these very beautiful structures."

By testing different dendrimers with different organic solvents, the research team found they could produce these onion-like vesicles and control the number of layers they contained. By changing the concentration of the dendrimers in the solvent, they could produce vesicles with as many as 20 layers when that solution was introduced to water. And because the layers are consistently spaced, the team could control the overall size of the vesicles by predicting the number of layers they could contain.

To actually see the multilayered structure of their vesicles, the researchers used a technique known as cryogenic transmission electron microscopy, or CryoTEM. This technique can take pictures of objects at the nanoscale floating in aqueous solution. To keep the fluid-floating vesicles in frame, the team flash-froze the sample, locking them in amorphous ice that was free of damaging ice crystals.

With the vesicles characterized, a host of clinical applications are possible. One of the more enticing is encapsulating drugs in these vesicles. Many drugs are not water-soluble, so they need to be packaged with some other chemistry to allow them to flow through the bloodstream. The additional stability of multiple bilayers makes these onion vesicles an attractive option, and their unique structure opens the door to next generation nanomedicine.

"If you want to deliver a single drug over the course of 20 days," Perce said, "you could think about putting one dose of the drug in each layer and have it released over time. Or you might put one drug in the first layer, another drug in the second and so on. Being able to control the diameter of the vesicles may also have clinical uses; target cells might only accept vesicles of a certain size."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Andrew D. Hughes is now a research scientist at the Dow Chemical Company. Annabelle Bertin is now an assistant professor at the Free University of Berlin.

Penn research develops 'onion' vesicles for drug delivery

2014-06-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NYU Langone internist calls for VA system reform

2014-06-10

An NYU Langone internal medicine specialist who served as a White House fellow at the US Department of Veteran's Affairs says the headline-grabbing failures of the VA health system's administration stand in sharp contrast to the highly rated care the system delivers.

In an editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine online June 5, Dave Chokshi, MD, MS, an assistant professor at NYU Langone Medical Center, says the paradox has created a watershed moment to reform and refocus the way the entire system is structured, staffed, and managed, while also building on its ...

Obstetric malpractice claims dip when hospitals stress patient safety

2014-06-10

A Connecticut hospital saw a 50% drop in malpractice liability claims and payments when it made patient safety initiatives a priority by training doctors and nurses to improve teamwork and communication, hiring a patient safety nurse, and standardizing practices, according to a study by Yale School of Medicine researchers.

The results, published in the June 9 online issue of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, come at a time when mounting concerns about liability are thinning the ranks of obstetricians in the United States, according first author Christian ...

LSTM researchers identify the complex mechanisms controlling changes in snake venom

2014-06-10

Specialist researchers from LSTM have identified the diverse mechanisms by which variations in venom occur in related snake species and the significant differences in venom pathology that occur as a consequence.

Working with colleagues from Bangor University and Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia in Spain, the team assessed the venom composition of six related viperid snakes, examining the differences in gene and protein expression that influence venom content. The research, published in PNAS, also assessed how these changes in venom composition impacted upon venom-induced ...

Grain legume crops sustainable, nutritious

2014-06-10

Popular diets across the world typically focus on the right balance of essential components like protein, fat, and carbohydrates. These items are called macronutrients, and we consume them in relatively large quantities. However, micronutrients often receive less attention. Micronutrients are chemicals, including vitamins and minerals, that our bodies require in very small quantities. Common mineral micronutrients include zinc, iron, manganese, magnesium, potassium, copper, and selenium.

A recent study published in Crop Science examined the mineral micronutrient content ...

Seafarers brought Neolithic culture to Europe, gene study indicates

2014-06-10

How the Neolithic people found their way to Europe has long been a subject of debate. A study published June 6 of genetic markers in modern populations may offer some new clues.

Their paper, "Maritime route of colonization of Europe," appears in the online edition of the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences.

Between 8,800 to 10,000 B.C., in the Levant, the region in the eastern Mediterranean that today encompasses Israel and the West Bank, Jordan, Syria and part of southern Turkey, people learned how to domesticate wild grains. This accomplishment eventually ...

In fighting obesity, targeting popular teens not all that effective

2014-06-10

MAYWOOD, Ill. – In the fight against teenage obesity, some researchers have proposed targeting popular teens, in the belief that such kids would have an outsize influence on their peers.

But in a Loyola University Chicago study, researchers were surprised to find that this strategy would be only marginally more effective than targeting overweight kids at random.

Results are published in the journal Social Science & Medicine.

"I don't think targeting popular kids would be worth the extra effort it would take to identify them," said David Shoham, PhD, MSPH, senior ...

Study: Little evidence that No Child Left Behind has hurt teacher job satisfaction

2014-06-10

WASHINGTON, D.C., June 10, 2014 ─ The conventional wisdom that No Child Left Behind (NCLB) has eroded teacher job satisfaction and commitment is off the mark, according to new research published online today in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association.

"Estimating the Effects of No Child Left Behind on Teachers and Their Work Environment," by Jason A. Grissom of Vanderbilt University, Sean Nicholson-Crotty of Indiana University, and James R. Harrington of the University of Texas at Dallas, ...

Scientific breakthrough: International collaboration has sequenced salmon genome

2014-06-10

Vancouver, BC - Today the International Cooperation to Sequence the Atlantic Salmon Genome (ICSASG) announced completion of a fully mapped and openly accessible salmon genome. This reference genome will provide crucial information to fish managers to improve the production and sustainability of aquaculture operations, and address challenges around conservation of wild stocks, preservation of at-risk fish populations and environmental sustainability. This breakthrough was announced at the International Conference on Integrative Salmonid Biology (ICISB) being held in Vancouver ...

Summertime cholesterol consumption key for wintertime survival for Siberian hamsters

2014-06-10

Increasingly, scientific findings indicate that an organism's diet affects more than just general health and body condition. In an article published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, researchers from Nicolaus Copernicus University have found evidence that the diet of some animals must include cholesterol in order for them to enter necessary periods of energy conservation known as torpor.

Torpor is a temporary, strategic decrease of body temperature and metabolic, heart, and respiration rates that can enable an organism to survive ...

RHM announces publication latest issue: Population, environment & sustainable development

2014-06-10

London, June 10, 2014 – Papers published in the latest themed issue of Reproductive Health Matters demonstrate the extent of evidence and progressive thinking around population dynamics and sustainability that is informing development policies and programs. The theme of this issue is timely given that meetings and negotiations are currently taking place around the world to decide what will be included in the post-2015 development goals.

The discussions about the post-2015 agenda have focused on calling out to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) advocates ...