(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. – Researchers have determined that a copper compound known for decades may form the basis for a therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease.

In a new study just published in the Journal of Neuroscience, scientists from Australia, the United States (Oregon), and the United Kingdom showed in laboratory animal tests that oral intake of this compound significantly extended the lifespan and improved the locomotor function of transgenic mice that are genetically engineered to develop this debilitating and terminal disease.

In humans, no therapy for ALS has ever been discovered that could extend lifespan more than a few additional months. Researchers in the Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University say this approach has the potential to change that, and may have value against Parkinson's disease as well.

"We believe that with further improvements, and following necessary human clinical trials for safety and efficacy, this could provide a valuable new therapy for ALS and perhaps Parkinson's disease," said Joseph Beckman, a distinguished professor of biochemistry and biophysics in the OSU College of Science.

"I'm very optimistic," said Beckman, who received the 2012 Discovery Award from the OHSU Medical Research Foundation as the leading medical researcher in Oregon.

ALS was first identified as a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease in the late 1800s and gained international recognition in 1939 when it was diagnosed in American baseball legend Lou Gehrig. It's known to be caused by motor neurons in the spinal cord deteriorating and dying, and has been traced to mutations in copper, zinc superoxide dismutase, or SOD1. Ordinarily, superoxide dismutase is an antioxidant whose proper function is essential to life.

When SOD1 is lacking its metal co-factors, it "unfolds" and becomes toxic, leading to the death of motor neurons. The metals copper and zinc are important in stabilizing this protein, and can help it remain folded more than 200 years.

"The damage from ALS is happening primarily in the spinal cord and that's also one of the most difficult places in the body to absorb copper," Beckman said. "Copper itself is necessary but can be toxic, so its levels are tightly controlled in the body. The therapy we're working toward delivers copper selectively into the cells in the spinal cord that actually need it. Otherwise, the compound keeps copper inert."

"This is a safe way to deliver a micronutrient like copper exactly where it is needed," Beckman said.

By restoring a proper balance of copper into the brain and spinal cord, scientists believe they are stabilizing the superoxide dismutase in its mature form, while improving the function of mitochondria. This has already extended the lifespan of affected mice by 26 percent, and with continued research the scientists hope to achieve even more extension.

The compound that does this is called copper (ATSM), has been studied for use in some cancer treatments, and is relatively inexpensive to produce.

"In this case, the result was just the opposite of what one might have expected," said Blaine Roberts, lead author on the study and a research fellow at the University of Melbourne, who received his doctorate at OSU working with Beckman.

"The treatment increased the amount of mutant SOD, and by accepted dogma this means the animals should get worse," he said. "But in this case, they got a lot better. This is because we're making a targeted delivery of copper just to the cells that need it.

"This study opens up a previously neglected avenue for new disease therapies, for ALS and other neurodegenerative disease," Roberts said.

INFORMATION:

Other collaborators on this research include OSU, the University of Melbourne, University of Technology/Sydney, Deakin University, the Australian National University, and the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

Funding has been provided by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Linus Pauling Institute and other groups in Australia and Finland.

Findings point toward one of first therapies for Lou Gehrig's disease

2014-06-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists identify Deepwater Horizon Oil on shore even years later, after most has degraded

2014-06-12

Years after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil spill, oil continues to wash ashore as oil-soaked "sand patties," persists in salt marshes abutting the Gulf of Mexico, and questions remain about how much oil has been deposited on the seafloor. Scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences have developed a unique way to fingerprint oil, even after most of it has degraded, and to assess how it changes over time. Researchers refined methods typically used to identify the source of oil spills and adapted them for application on a ...

Anti-dsDNA, surface-expressed TLR4 and endosomal TLR9 cooperate to exacerbate lupus

2014-06-12

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complicated multifactorial autoimmune disease influenced by many genetic and environmental factors. The hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the presence of high levels of anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibody (anti-dsDNA) in sera. In addition, greater infection rates are found in SLE patients and higher morbidity and mortality usually come from bacterial infections. Deciphering interactions between the susceptibility genes and the environmental factors for lupus complex traits is challenging and has resulted in only ...

Protein anchors help keep embryonic development 'just right'

2014-06-12

The "Goldilocks effect" in fruit fly embryos may be more intricate than previously thought. It's been known that specific proteins, called histones, must exist within a certain range—if there are too few, a fruit fly's DNA is damaged; if there are too many, the cell dies. Now research out of the University of Rochester shows that different types of histone proteins also need to exist in specific proportions. The work further shows that cellular storage facilities keep over-produced histones in reserve until they are needed.

Associate Professor of Biology Michael Welte ...

Penn study describes new models for testing Parkinson's disease immune-based drugs

2014-06-12

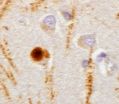

PHILADELPHIA - Using powerful, newly developed cell culture and mouse models of sporadic Parkinson's disease (PD), a team of researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, has demonstrated that immunotherapy with specifically targeted antibodies may block the development and spread of PD pathology in the brain. By intercepting the distorted and misfolded alpha-synuclein (α-syn) proteins that enter and propagate in neurons, creating aggregates, the researchers prevented the development of pathology and also reversed some of the ...

Viral infections, including flu, could be inhibited by naturally occurring protein

2014-06-12

PITTSBURGH, June 12, 2014 – By boosting a protein that naturally exists in our cells, an international team of researchers led by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), partner with UPMC CancerCenter, has found a potential way to enhance our ability to sense and inhibit viral infections.

The laboratory-based discovery, which could lead to more effective treatments for viruses ranging from hepatitis C to the flu, appears in the June 19 issue of the journal Immunity. The research is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

"Despite remarkable advances ...

African-Americans respond better to first-line diabetes drug than whites

2014-06-12

Washington, DC—African Americans taking the diabetes drug metformin saw greater improvements in their blood sugar control than white individuals who were prescribed the same medication, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

An estimated 29 million Americans have diabetes. African Americans are twice as likely to be diagnosed with diabetes as whites and have a higher rate of complications such as kidney failure, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Minority ...

Brain power

2014-06-12

VIDEO:

Real-time movie of changes in total hemoglobin in the brain during stimulation. The initial blush of the brain is followed quickly by dilation (red) of arteries on the brain's surface....

Click here for more information.

New York, NY—June 12, 2014—In a new study published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association June 12, 2014, researchers at Columbia Engineering report that they have identified a new component of the biological mechanism that controls ...

Time-lapse study reveals bottlenecks in stem cell expansion

2014-06-12

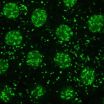

A time-lapse study of human embryonic stems cells has identified bottlenecks restricting the formation of colonies, a discovery that could lead to improvement in their use in regenerative medicine.

Biologists at the University of Sheffield's Centre for Stem Cell Biology led by Professor Peter Andrews and engineers in the Complex Systems and Signal Processing Group led by Professor Daniel Coca studied human pluripotent stem cells, which are a potential source of cells for regenerative medicine because they have the ability to produce any cell type in the body.

However, ...

Synchronized brain waves enable rapid learning

2014-06-12

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The human mind can rapidly absorb and analyze new information as it flits from thought to thought. These quickly changing brain states may be encoded by synchronization of brain waves across different brain regions, according to a new study from MIT neuroscientists.

The researchers found that as monkeys learn to categorize different patterns of dots, two brain areas involved in learning — the prefrontal cortex and the striatum — synchronize their brain waves to form new communication circuits.

"We're seeing direct evidence for the interactions between ...

Scientists find trigger to decode the genome

2014-06-12

Scientists from The University of Manchester have identified an important trigger that dictates how cells change their identity and gain specialised functions.

And the research, published today in Cell Reports, has brought them a step closer to being able to decode the genome.

The scientists have found out how embryonic stem cell fate is controlled which will lead to future research into how cells can be artificially manipulated.

Lead author Andrew Sharrocks, Professor in Molecular Biology at The University of Manchester, said: "Understanding how to manipulate cells ...