(Press-News.org) Confirming what neurocomputational theorists have long suspected, researchers at the Dignity Health Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz. and University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report that the human brain locks down episodic memories in the hippocampus, committing each recollection to a distinct, distributed fraction of individual cells.

The findings, published in the June 16 Early Edition of PNAS, further illuminate the neural basis of human memory and may, ultimately, shed light on new treatments for diseases and conditions that adversely affect it, such as Alzheimer's disease and epilepsy.

"To really understand how the brain represents memory, we must understand how memory is represented by the fundamental computational units of the brain – single neurons – and their networks," said Peter N. Steinmetz, MD, PhD, program director of neuroengineering at Barrow and senior author of the study. "Knowing the mechanism of memory storage and retrieval is a critical step in understanding how to better treat the dementing illnesses affecting our growing elderly population."

Steinmetz, with first author John T. Wixted, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Larry R. Squire, PhD, professor in the departments of neurosciences, psychiatry and psychology, both at UC San Diego, and colleagues, assessed nine patients with epilepsy whose brains had been implanted with electrodes to monitor seizures. The monitoring recorded activity at the level of single neurons.

The patients memorized a list of words on a computer screen, then viewed a second, longer list that contained those words and others. They were asked to identify words they had seen earlier, and to indicate how well they remembered them. The observed difference in the cell-firing activity between words seen on the first list and those not on the list clearly indicated that cells in the hippocampus were representing the patients' memories of the words.

The researchers found that recently viewed words were stored in a distributed fashion throughout the hippocampus, with a small fraction of cells, about 2 percent, responding to any one word and a small fraction of words, about 3 percent, producing a strong change in firing in these cells.

"Intuitively, one might expect to find that any neuron that responds to one item from the list would also respond to the other items from the list, but our results did not look anything like that. The amazing thing about these counterintuitive findings is that they could not be more in line with what influential neurocomputational theorists long ago predicted must be true," said Wixted.

Although only a small fraction of cells coded recent memory for any one word, the scientists said the absolute number of cells coding memory for each word was large nonetheless – on the order of hundreds of thousands at least. Thus, the loss of any one cell, they noted, would have a negligible impact on a person's ability to remember specific words recently seen.

Ultimately, the scientists said their goal is to fully understand how the human brain forms and represents memories of places and things in everyday life, which cells are involved and how those cells are affected by illness and disease. The researchers will next attempt to determine whether similar coding is involved in memories of pictures of people and landmarks and how hippocampal cells representing memory are impacted in patients with more severe forms of epilepsy.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Yoonhee Jang, University of Montana; Megan H. Papesh, Louisiana State University; Stephen D. Goldinger, Arizona State University; Joel Kuhn, UCSD; Kris A. Smith and David M. Treiman, Barrow Neurological Institute.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute of Mental Health (grant 24600), the National Institute for Deafness and Other Communications Disorders (grant 1R21DC009781), the Barrow Neurological Foundation, the Arizona Biomedical Research Council and the UC San Diego Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind.

How our brains store recent memories, cell by single cell

Findings may shed light on how to treat neurological conditions like Alzheimer's and epilepsy

2014-06-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Omega (ω)-3 inhibits blood vessel growth in a model of age-related macular degeneration in vivo

2014-06-16

Boston (June 16, 2014) – Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is characterized by choroidal neovascularization (CNV), or blood vessel growth, is the primary cause of blindness in elderly individuals of industrialized countries. The prevalence of the disease is projected to increase 50% by the year 2020. There is an urgent need for new pharmacological interventions for the treatment and prevention of AMD.

Researchers from Massachusetts Eye and Ear/Schepens Eye Research Institute, Harvard Medical School and other institutions have demonstrated for the first time ...

Caterpillars that eat multiple plant species are more susceptible to hungry birds

2014-06-16

Irvine, Calif. — For caterpillars, having a well-rounded diet can be fraught with peril.

UC Irvine and Wesleyan University biologists have learned that caterpillars that feed on one or two plant species are better able to hide from predatory birds than caterpillars that consume a wide variety of plants.

This is probably because the color patterns and hiding behaviors of the caterpillar "specialists" have evolved to allow them to blend into the background flora more effectively than caterpillars that eat many different plant species. Moving among these diverse plant ...

Hunt for extraterrestrial life gets massive methane boost

2014-06-16

A powerful new model to detect life on planets outside of our solar system, more accurately than ever before, has been developed by UCL (University College London) researchers.

The new model focuses on methane, the simplest organic molecule, widely acknowledged to be a sign of potential life.

Researchers from UCL and the University of New South Wales have developed a new spectrum for 'hot' methane which can be used to detect the molecule at temperatures above that of Earth, up to 1,500K/1220°C – something which was not possible before.

To find out what remote planets ...

Physician anesthesiologists identify 5 tests and procedures to avoid

2014-06-16

Proving that less really is more, five specific tests or procedures commonly performed in anesthesiology that may not be necessary and, in some cases should be avoided, will be published online June 16 in JAMA Internal Medicine. The "Top-five" list was created by the American Society of Anesthesiologists® (ASA®) for inclusion in the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely® campaign.

"The Top-five list of activities to question in anesthesiology was developed in an effort to reduce unnecessary, costly procedures and improve patient care," said Onyi Onuoha, M.D., M.P.H., lead ...

Your genes affect your betting behavior

2014-06-16

Investors and gamblers take note: your betting decisions and strategy are determined, in part, by your genes.

University of California, Berkeley, and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) researchers have shown that betting decisions in a simple competitive game are influenced by the specific variants of dopamine-regulating genes in a person's brain.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter – a chemical released by brain cells to signal other brain cells – that is a key part of the brain's reward and pleasure-seeking system. Dopamine deficiency leads to Parkinson's ...

When genes play games

2014-06-16

Berkeley — What do you get when you mix theorists in computer science with evolutionary biologists? You get an algorithm to explain sex.

It turns out that 155 years after Charles Darwin first published "On the Origin of Species," vexing questions remain about key aspects of evolution, such as how sexual recombination and natural selection produced the teeming diversity of life that exists today.

The answer could lie in the game that genes play during sexual recombination, and computer theorists at the University of California, Berkeley, have identified an algorithm ...

Quantum biology: Algae evolved to switch quantum coherence on and off

2014-06-16

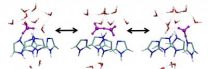

A UNSW Australia-led team of researchers has discovered how algae that survive in very low levels of light are able to switch on and off a weird quantum phenomenon that occurs during photosynthesis.

The function in the algae of this quantum effect, known as coherence, remains a mystery, but it is thought it could help them harvest energy from the sun much more efficiently.

Working out its role in a living organism could lead to technological advances, such as better organic solar cells and quantum-based electronic devices.

The research is published in the journal Proceedings ...

Quantum theory reveals puzzling pattern in how people respond to some surveys

2014-06-16

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers used quantum theory – usually invoked to describe the actions of subatomic particles – to identify an unexpected and strange pattern in how people respond to survey questions.

By conventional standards, the results are surprising: The scientists found the exact same pattern in 70 nationally representative surveys from Gallup and the Pew Research center taken from 2001 to 2011, as well as in two laboratory experiments. Most of the national surveys included more than 1,000 respondents in the United States.

"Human behavior is very sensitive ...

Computation leads to better understanding of influenza virus replication

2014-06-16

Treating influenza relies on drugs such as Amantadine that are becoming less and less effective due to viral evolution. But University of Chicago scientists have published computational results that may give drug designers the insight they need to develop the next generation of effective influenza treatment.

"It's very hard to design a drug if you don't understand how the disease functions," said Gregory Voth, the Haig P. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor in Chemistry. Voth and three co-authors offer new insights into the disease's functioning in the Proceedings ...

Chemical strategy hints at better drugs for osteoporosis, diabetes

2014-06-16

MADISON, Wis. — By swapping replacement parts into the backbone of a synthetic hormone, UW–Madison graduate student Ross Cheloha and his mentor, Sam Gellman, along with collaborators at Harvard Medical School, have built a version of a parathyroid hormone that resists degradation in laboratory mice. As a result, the altered hormone can stay around longer — and at much higher concentration, says Gellman, professor of chemistry at the UW.

Hormones are signaling molecules that are distributed throughout the body, usually in the blood. Hormones elicit responses from only ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] How our brains store recent memories, cell by single cellFindings may shed light on how to treat neurological conditions like Alzheimer's and epilepsy