(Press-News.org) "Increased to levels unprecedented" is how the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) described the rise of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions in their report on the physical science basis of climate change in 2013. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the atmospheric concentration of methane, a greenhouse gas some 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide has been steadily growing since the 18th century and has now increased by 50 percent compared to pre-industrial levels, exceeding 1,800 parts per billion.

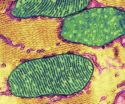

The EPA attributes one-fifth of methane emissions to livestock such as cattle, sheep and other ruminants. In fact, ruminant livestock are the single largest source of methane emissions, and in a country like New Zealand (NZ), where the sheep outnumber people 7 to 1, that's a big deal. However, not all ruminants are equal when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions. It turns out that the amount of methane produced varies substantially across individual animals of the same ruminant species. To find out why this is so, a team of researchers led by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI) deployed high throughput DNA sequencing and specialized analysis techniques to explore the contents of the rumens of sheep in collaboration with NZ's AgResearch Limited to see what role ruminant "microbiomes" (the microbes living in the rumen) play in this process. The study was published online June 6, 2014 in Genome Research.

"We wanted to understand why some sheep produce a lot and some produce little methane," said DOE JGI Director Eddy Rubin. "The study shows that it is purely the microbiota responsible for the difference."

To learn why the amount of methane that ruminants produce varies, the researchers took advantage of a large sheep screening and breeding program in NZ that aims to breed low methane-emitting ruminants without impacting other traits such as reproduction and wool and meat quality. The team measured the methane yields from a cohort of 22 sheep, and from this group, they selected four sheep with the lowest methane emissions, four sheep with the highest emissions and two sheep with intermediate emission levels. Rumen metagenome DNA samples collected on two occasions from the 10 sheep were sequenced at the DOE JGI, generating 50 billion bases of data each.

"The deep sequencing study contributes to this breeding program by defining the microbial contribution to the methane trait, which can be used in addition to methane measurements to assist in animal selection," said senior scientist Graeme Attwood of AgResearch Limited, a senior author on the paper.

The team then checked to see if there was a correlation between the proportions of methanogens in the eight sheep with the highest and lowest recorded methane emissions. In sheep with low methane emissions, they found elevated levels of one particular species of methanogen (Methanosphaera) while sheep with high methane emissions had elevated levels of another group of methanogens (Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii). Exploring further, the team then identified a methane-producing pathway and three variants of a gene encoding an important methane-forming reaction that were involved in elevated methane yields. While the overall changes to the methane-producing microbial community structure and methanogen abundance across sheep were rather subtle, the team reported that the expression levels of genes involved in methane production varied more substantially across sheep, suggesting differential gene regulation, perhaps controlled by hydrogen concentration in the rumen or by variations in the dwell time of their feed.

"It's not so much the actual composition of the microbiome that determines emission—which conventional wisdom would suggest—but mostly transcriptional regulation within the existing microbes that makes the difference, which is a concept that is relatively new in metagenomic studies," Rubin said. The team's findings suggest new possible targets for mitigating methane emissions at the microbiome level.

Screening and breeding for low-methane producing sheep is still underway, and importantly, low-methane lines then need to be tested for stability of the trait, as well as the absence of any impacts on fertility or meat or wool production. Moreover, as Attwood notes, "there needs to be an incentive for farmers to incorporate low methane animals into their flocks, that is, achieving better performance with the low methane animals or being able to claim carbon credits. If everything went well you could expect introduction of the low methane trait to begin in three years, and for there to be slow but incremental changes to the sheep industry in subsequent years."

The DOE Office of Science supported the sheep rumen research at the DOE JGI. The NZ Fund for Global Partnerships in Livestock Emissions Research funded the work done in NZ to support the objectives of the Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases, and the NZ Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre and the NZ Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium made the methane screening data and animal resources available. The data from the study complement the genomic sequences being generated from the Hungate1000 project which seeks to produce a reference set of rumen microbial genomes from cultivated rumen bacteria and archaea, together with representative cultures of rumen anaerobic fungi and ciliate protozoa.

INFORMATION:

The U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, supported by the DOE Office of Science, is committed to advancing genomics in support of DOE missions related to clean energy generation and environmental characterization and cleanup. DOE JGI, headquartered in Walnut Creek, Calif., provides integrated high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis that enable systems-based scientific approaches to these challenges. Follow @doe_jgi on Twitter.

DOE's Office of Science is the largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Study reveals livestock gut microbes contributing to greenhouse gas emissions

2014-06-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Vital signs' of teaching captured by quick, reliable in-class evaluation

2014-06-17

A 20-minute classroom assessment that is less subjective than traditional in-class evaluations by principals can reliably measure classroom instruction and predict student standardized test scores, a team of researchers researchers reported.

The assessment also provides immediate and meaningful feedback making it an important new tool for understanding and improving instructional quality, according to psychologists from the University of Rochester and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"Education researchers broadly agree that teachers matter," explained ...

EHRA White Book 2014 highlights growing use of complex therapies for heart rhythm abnormalities

2014-06-17

Nice, France, 17 June 2014. The EHRA (European Heart Rhythm Association) White Book 2014 will be officially launched at the CARDIOSTIM EHRA EUROPACE 2014 congress which starts today in Nice, France.

The White Book reports on the current status of arrhythmia treatment in 49 of the 56 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) member countries for the year 2013. The new White Book is published in electronic format only and will be distributed on a USB stick as well as being available on the EHRA website. As a new feature, the USB stick contains complete data also from the six ...

Distracted minds still see blurred lines

2014-06-17

VIDEO:

Participants were asked to look at an image with moving sections blurred, while performing a cognitive 'n-back' task.

Click here for more information.

Montreal, June 17, 2014 — From animated ads on Main Street to downtown intersections packed with pedestrians, the eyes of urban drivers have much to see. But while city streets have become increasingly crowded with distractions, our ability to process visual information has remained unchanged for millions of years. ...

Pain pilot explores hand shiatsu treatment as sleep aid

2014-06-17

(Edmonton) There was a time, back in Nancy Cheyne's youth, when she combined the poise and grace of a ballerina with the daring and grit of a barrel racer. When she wasn't pursuing either of those pastimes, she bred sheepdogs, often spending hours on her feet grooming her furry friends at dog shows.

All that seems like a lifetime ago. After 15 years of living with chronic lower-back pain, Cheyne, 64, can't walk from the disabled parking stall to the elevator at work without stopping for a rest. She eats mostly junk food because it hurts too much to stand over the stove ...

Single dose reverses autism-like symptoms in mice

2014-06-17

In a further test of a novel theory that suggests autism is the consequence of abnormal cell communication, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report that an almost century-old drug approved for treating sleeping sickness also restores normal cellular signaling in a mouse model of autism, reversing symptoms of the neurological disorder in animals that were the human biological age equivalent of 30 years old.

The findings, published in the June 17, 2014 online issue of Translational Psychiatry, follow up on similar research published ...

Breast cancer diagnosis, mammography improved by considering patient risk: INFORMS paper

2014-06-17

A new approach to examining mammograms that takes into account a woman's health risk profile would reduce the number of cancer instances missed and also cut the number of false positives, according to a paper being presented at a conference of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS).

Mehmet U.S. Ayvaci of the University of Texas Dallas will present his research group's findings about the role of risk profiling in the interpretation of mammograms at Advances in Decision Analysis, a conference sponsored by the INFORMS Decision Analysis ...

Boost for dopamine packaging protects brain in Parkinson's model

2014-06-17

Researchers from Emory's Rollins School of Public Health discovered that an increase in the protein that helps store dopamine, a critical brain chemical, led to enhanced dopamine neurotransmission and protection from a Parkinson's disease-related neurotoxin in mice.

Dopamine and related neurotransmitters are stored in small storage packages called vesicles by the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2). When released from these packages dopamine can help regulate movement, pleasure, and emotional response. Low dopamine levels are associated with neurodegenerative diseases ...

Gut bacteria predict survival after stem cell transplant, study shows

2014-06-17

(WASHINGTON, June 17, 2014) – New research, published online today in Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology, suggests that the diversity of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract of patients receiving stem cell transplants may be an important predictor of their post-transplant survival.

A healthy gastrointestinal tract contains a balanced community of microorganisms (known as microbiota), largely comprised of "friendly" bacteria that aid digestion and are important to immune system function. When this community of microbes is compromised, the microbiota ...

Ice cream chemistry: The inside scoop on a classic summer treat (video)

2014-06-17

WASHINGTON, June 17, 2014 — The summer weather is here, and if you've been out in the sun, you're probably craving some ice cream to cool off. In the American Chemical Society's latest Reactions video, American University Assistant Professor Matt Hartings, Ph.D., breaks down the chemistry of this favorite frozen treat, including what makes ice cream creamy or crunchy, and why it is so sweet. The video is available at http://youtu.be/-rlapUkWCSM

INFORMATION:

Subscribe to the series at Reactions YouTube, and follow us on Twitter @ACSreactions to be the first to see our ...

Climate change deflecting attention from biodiversity loss

2014-06-17

New research from the University of Kent suggests that recent high levels of media coverage for climate change may have deflected attention and funding from biodiversity loss.

In a paper published by the journal Bioscience, Kent conservationists also recommend that, to prevent biodiversity from becoming a declining priority, conservationists need to leverage the importance of climate change to obtain more funds and draw attention to other research areas such as biodiversity conservation.

For the study, the team conducted a content analysis of newspaper coverage in ...