(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A neuroscience study provides new insight into the primal brain circuits involved in collision avoidance, and perhaps a more general model of how neurons can participate in networks to process information and act on it.

In the study, Brown University neuroscientists tracked the cell-by-cell progress of neural signals from the eyes through the brains of tadpoles as they saw and reacted to stimuli including an apparently approaching black circle. In so doing, the researchers were able to gain a novel understanding of how individual cells contribute in a broader network that distinguishes impending collisions.

The basic circuitry involved is present in a wide variety of animals, including people, which is no surprise given how fundamental collision avoidance is across animal behavior.

"Imagine yourself walking in a forest while keeping a conversation with your friend," said Arseny Khakhalin, neuroscience postdoctoral scholar at Brown and lead author of the study in the European Journal of Neuroscience. "You can totally keep the conversation going, and at the same time avoid tree trunks and shrubs without even thinking about them consciously. That's because you have a whole region in your brain that is dedicated, among other things, to this task."

Turning tail

To learn how collision avoidance works, Khakhalin studied the task using tadpoles as a model organism, because as senior author and neuroscience professor Carlos Aizenman put it, they are "sufficiently complex to produce interesting behavior, but have nervous systems sufficiently simple to address in an integrated experimental approach."

They started with the avoidance behavior. With tadpoles in a dish atop a screen, they projected digital black dots, representing virtual objects, of varying widths, at varying speeds and angles of approach. They also just flashed dots in place. The tadpoles would flee approaching dots as long as they reached a certain threshold angular size, but rarely reacted to the dots that merely blinked onto the scene but weren't moving toward them. The response confirmed that tadpoles can distinguish approaching rather than merely proximate visual stimuli.

The researchers then sought to determine how the tadpoles process different stimuli. To do that they held the tadpoles in place while presenting a variety of simple animations via a fiber optic cable held next to an eye. The animations included a flashed circle, an apparently approaching circle (it became larger and larger), and a couple of "in between" animations, such as a circle that was faded in, rather than simply flashed into being.

While the tadpoles watched the animations, the researchers tracked their tail movements with a high-speed camera (to determine if the tadpoles were executing a fleeing maneuver) and recorded electrical signals along the visual processing circuitry: at the optic nerve leading from the retina to the brain's optic tectum region, at "excitatory" and "inhibitory" synaptic inputs of neurons in the optic tectum, and at the outputs of the tectal neurons.

What the scientists found was that the tectum, rather than the retina, appears to be where the tadpoles determine that something is approaching rather than merely present. How did they know? The strongest difference between responses to the apparently approaching circle, versus responses to other stimuli, such as flashed or faded circles, was detected at the stage of output from tectal neurons.

Moreover, the difference in activity related to approaching vs. flashed circles increased as the signal propagated from the optic nerve, through tectum input, and to tectum output.

"The tectum is the first place that responded to approaching stimuli not just differently, but stronger," Khakhalin said.

Inhibition moderates the conversation

An implication of the experiments was that when individual neurons in the tectum are uniquely activated by an apparently approaching stimulus, they collectively generate a signal to send to downstream parts of the brain that can get the tail moving to avoid the collision.

That's indeed what excitatory neurons do, but the researchers wanted to know what role the inhibitory neurons were playing, especially because the balance of inhibitory and excitatory activity in the tectum varied with different stimuli.

To find out, they chemically blocked inhibitory neurons in the tectum in some tadpoles, chemically enhanced their activity in others and left still other tadpoles unaltered as controls. They found that when they altered the degree of inhibition in either direction, the output selectivity for an oncoming stimulus was lost. When inhibition was blocked, the individual excitatory cells lost their selectivity, too. When inhibition was enhanced, the individual excitatory cells retained their selectivity but could not project a signal collectively.

Khakhalin said the evidence seems to support the idea of inhibitory cells as facilitators of network function. They were not necessarily responsible for making the tectum selective. Instead, their ability to moderate excitation allowed the network of cells to function so that an organized signal from the individual excitatory neurons could emerge from the tectum.

The team was able to use these findings to create a conceptual model of the collision stimulus circuitry.

Khakhalin's hypothesis of how it works is that inhibitory/excitatory balance allows the tectum to build up a necessary degree of excitement about the stimulus of interest (e.g. something has been getting bigger) while still allowing enough "calm" to consider the next moment wave of input (it just got bigger again).

Aizenman said the paper illustrates broader approach that his lab is applying to fundamental neuroscience questions.

"It is part of a greater project to be able to take an entire behavior and break it down into all of its neuronal components, to build a model in which we can understand how activity in single neurons and in the connections between them can all synergize to produce a behavior," he said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Khakhalin and Aizenman, other authors are former Brown undergraduates David Koren and Jenny Gu, and physics graduate student Heng Xu.

The National Science Foundation, the National Eye Institute and the Fox Foundation Fellowship for the Visual Sciences supported the research.

Dodging dots helps explain brain circuitry

2014-07-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Satellites reveal possible catastrophic flooding months in advance, UCI finds

2014-07-07

Irvine, Calif., July 7, 2014 – Data from NASA satellites can greatly improve predictions of how likely a river basin is to overflow months before it does, according to new findings by UC Irvine. The use of such data, which capture a much fuller picture of how water is accumulating, could result in earlier flood warnings, potentially saving lives and property.

The research was published online Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

A case study of the catastrophic 2011 Missouri River floods showed that factoring into hydrologic models the total water storage information ...

Why 'whispers' among bees sometimes evolve into 'shouts'

2014-07-07

Let's say you're a bee and you've spotted a new and particularly lucrative source of nectar and pollen. What's the best way to communicate the location of this prize cache of food to the rest of your nestmates without revealing it to competitors, or "eavesdropping" spies, outside of the colony?

Many animals are thought to deter eavesdroppers by making their signals revealing the location or quality of resources less conspicuous to outsiders. In essence, they've evolved "whispers" in their signals to counter eavesdropping.

But some species of bees in Brazil do the exact ...

Obesity, large waist size risk factors for COPD

2014-07-07

Obesity, especially excessive belly fat, is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), according to an article in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Excessive belly fat and low physical activity are linked to progression of the disease in people with COPD, but it is not known whether these modifiable factors are linked to new cases.

A team of researchers in Germany and the United States looked at the relationship of waist and hip circumference, body mass index (BMI) and physical activity levels to new cases of COPD in a large group of men ...

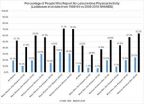

Less exercise, not more calories, responsible for expanding waistlines

2014-07-07

Philadelphia, PA, July 7, 2014 – Sedentary lifestyle and not caloric intake may be to blame for increased obesity in the US, according to a new analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). A study published in the American Journal of Medicine reveals that in the past 20 years there has been a sharp decrease in physical exercise and an increase in average body mass index (BMI), while caloric intake has remained steady. Investigators theorized that a nationwide drop in leisure-time physical activity, especially among young women, may ...

Mind the gap: Socioeconomic status may influence understanding of science

2014-07-07

MADISON — When it comes to science, socioeconomic status may widen confidence gaps among the least and most educated groups in society, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Science, Media and the Public research group.

The findings, published in June in the journal Science Communication, show that similar levels of attention to science in newspapers and on blogs can lead to vastly different levels of factual and perceived knowledge between the two groups.

Notably, frequent science blog readership among low socioeconomic-status ...

Mechanism that prevents lethal bacteria from causing invasive disease is revealed

2014-07-07

An important development in understanding how the bacterium that causes pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia remains harmlessly in the nose and throat has been discovered at the University of Liverpool's Institute of Infection and Global Health.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a 'commensal', which can live harmlessly in the nasopharynx as part of the body's natural bacterial flora. However, in the very young and old it can invade the rest of the body, leading to serious diseases such as pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis, which claim up to a million lives every year worldwide. ...

Non-diet approach to weight management more effective in worksite wellness programs

2014-07-07

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Problematic eating behaviors and dissatisfaction with one's body are familiar struggles among women. To combat those behaviors, which have led to higher healthcare premiums and medical trends, employers have offered worksite wellness programs to employees and their families. However, the vast majority of wellness programs limit their approach to promoting diets, which may result in participants regaining the majority of their weight once the programs end. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have found that "Eat for Life," a new wellness approach ...

IPCC must consider alternate policy views, researchers say

2014-07-07

In addition to providing regular assessments of scientific literature, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Process (IPCC) also produces a "Summary for Policymakers" intended to highlight relevant policy issues through data.

While the summary presents powerful scientific evidence, it goes through an approval process in which governments can question wording and the selection of findings but not alter scientific facts or introduce statements at odds with the science. In particular, during this process, the most recent summary on mitigation policies was stripped ...

Teen dating violence cuts both ways: 1 in 6 girls and guys are aggressors, victims or both

2014-07-07

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Dating during the teen years takes a violent turn for nearly 1 in 6 young people, a new study finds, with both genders reporting acts like punching, pulling hair, shoving, and throwing things.

The startling number, drawn from a University of Michigan Medical School survey of more than 4,000 adolescent patients ages 14 to 20 seeking emergency care, indicates that dating violence is common and affects both genders.

Probing deeper, the study finds that those with depression, or a history of using drugs or alcohol, have a higher likelihood to act as ...

Taking a short smartphone break improves employee well-being, research finds

2014-07-07

MANHATTAN, KAN. — Want to be more productive and happier during the workday? Try taking a short break to text a friend, play "Angry Birds" or check Facebook on your smartphone, according to Kansas State University research.

In his latest research, Sooyeol Kim, doctoral student in psychological sciences, found that allowing employees to take smartphone microbreaks may be a benefit — rather than a disruption — for businesses. Microbreaks are nonworking-related behaviors during working hours.

Through a study of 72 full-time workers from various industries, Kim discovered ...