(Press-News.org) Re-examination of a circa 100,000-year-old archaic early human skull found 35 years ago in Northern China has revealed the surprising presence of an inner-ear formation long thought to occur only in Neandertals.

"The discovery places into question a whole suite of scenarios of later Pleistocene human population dispersals and interconnections based on tracing isolated anatomical or genetic features in fragmentary fossils," said study co-author Erik Trinkaus, PhD, a physical anthropology professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

"It suggests, instead, that the later phases of human evolution were more of a labyrinth of biology and peoples than simple lines on maps would suggest."

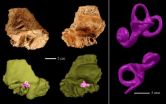

The study, forthcoming in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is based on recent micro-CT scans revealing the interior configuration of a temporal bone in a fossilized human skull found during 1970s excavations at the Xujiayao site in China's Nihewan Basin.

Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences, is a leading authority on early human evolution and among the first to offer compelling evidence for interbreeding and gene transfer between Neandertals and modern human ancestors.

His co-authors on this study are Xiu-Jie Wu, Wu Liu and Song Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, and Isabelle Crevecoeur of PACEA, Université de Bordeaux.

"We were completely surprised," Trinkaus said. "We fully expected the scan to reveal a temporal labyrinth that looked much like a modern human one, but what we saw was clearly typical of a Neandertal. This discovery places into question whether this arrangement of the semicircular canals is truly unique to the Neandertals."

Often well-preserved in mammal skull fossils, the semicircular canals are remnants of a fluid-filled sensing system that helps humans maintain balance when they change their spatial orientations, such as when running, bending over or turning the head from side-to-side.

Since the mid-1990s, when early CT-scan research confirmed its existence, the presence of a particular arrangement of the semicircular canals in the temporal labyrinth has been considered enough to securely identify fossilized skull fragments as being from a Neandertal. This pattern is present in almost all of the known Neandertal labyrinths. It has been widely used as a marker to set them apart from both earlier and modern humans.

The skull at the center of this study, known as Xujiayao 15, was found along with an assortment of other human teeth and bone fragments, all of which seemed to have characteristics typical of an early non-Neandertal form of late archaic humans.

Trinkaus, who has studied Neandertal and early human fossils from around the globe, said this discovery only adds to the rich confusion of theories that attempt to explain human origins, migrations patterns and possible interbreedings.

While it's tempting to use the finding of a Neandertal-shaped labyrinth in an otherwise distinctly "non-Neandertal" sample as evidence of population contact (gene flow) between central and western Eurasian Neandertals and eastern archaic humans in China, Trinkaus and colleagues argue that broader implications of the Xujiayao discovery remain unclear.

"The study of human evolution has always been messy, and these findings just make it all the messier," Trinkaus said. "It shows that human populations in the real world don't act in nice simple patterns.

"Eastern Asia and Western Europe are a long way apart, and these migration patterns took thousands of years to play out," he said. "This study shows that you can't rely on one anatomical feature or one piece of DNA as the basis for sweeping assumptions about the migrations of hominid species from one place to another."

INFORMATION:

Discovery of Neandertal trait in ancient skull raises new questions about human evolution

Modern humans emerged from a complex 'labyrinth of biology and peoples,' findings suggest

2014-07-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bruce Museum scientist identifies world's largest-ever flying bird

2014-07-07

GREENWICH, CT, EMBARGOED UNTIL JULY 7, 2014 (3:00 PM EST) -- Scientists have identified the fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird that is likely to have the largest wingspan of any bird ever to have lived. A paper announcing the findings, "Flight Performance of the Largest Volant Bird," was published July 7 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and is authored by Dr. Daniel Ksepka, the newest Curator of Science at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich.

With a wingspan of 20 to 24 feet, Pelagornis sandersi was more than twice as big as the Royal ...

Scientist identifies world's biggest-ever flying bird

2014-07-07

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have identified the fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird that could be the biggest flying bird ever found. With an estimated 20-24-foot wingspan, the creature surpassed size estimates based on wing bones from the previous record holder -- a long-extinct bird named Argentavis magnificens -- and was twice as big as the Royal Albatross, the largest flying bird today. Scheduled to appear online the week of July 7, 2014, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the findings show that the creature was an extremely efficient ...

Mathematical model illustrates our online 'copycat' behavior

2014-07-07

Researchers from the University of Oxford, the University of Limerick, and the Harvard School of Public Health have developed a mathematical model to examine online social networks, in particular the trade-off between copying our friends and relying on 'best-seller' lists.

The researchers examined how users are influenced in the choice of apps that they install on their Facebook pages by creating a mathematical model to capture the dynamics at play. By incorporating data from the installation of Facebook apps into their mathematical model, they found that users selected ...

Time of day crucial to accurately test for diseases, new research finds

2014-07-07

A new study published today in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), has found that time of day and sleep deprivation have a significant effect on our metabolism. The finding could be crucial when looking at the best time of day to test for diseases such as cancer and heart disease, and for administering medicines effectively.

Researchers from the University of Surrey and The Institute of Cancer Research, London, investigated the links between sleep deprivation, body clock disruption and metabolism, and discovered a clear variation in metabolism ...

The quantum dance of oxygen

2014-07-07

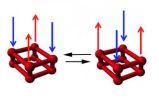

Perhaps not everyone knows that oxygen has – quite unusually for such a simple molecule – magnetic properties. The phase diagram of solid oxygen at low temperatures and high pressures shows, however, several irregularities (for example, proper "information gaps" with regard to these magnetic properties) that are still poorly understood. A team of researchers from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) and International Centre for Theoretical Physics Abdus Salam (ICTP) of Trieste, while trying to understand the origin of these phenomena, have identified a ...

DNA of 'Evolution Canyon' fruit flies reveals drivers of evolutionary change

2014-07-07

Scientists have long puzzled over the genetic differences between fruit flies that live hardly a puddle jump apart in a natural environment known as "Evolution Canyon" in Mount Carmel, Israel.

Now, an international team of researchers led by scientists with the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Tech has peered into the DNA of these closely related flies to discover how these animals have been able to adapt and survive in such close, but extremely different, ecologies.

One reason lies in a startling abundance of repetitive DNA elements that, until recently, ...

High earners in a stock market game have brain patterns that can predict market bubbles

2014-07-07

If you're so smart, why aren't you rich? It may be that, when it comes to stock market success, your brain is heeding the wrong neural signals.

In a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, scientists at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and Caltech found that, when they simulated market conditions for groups of investors, economic bubbles — in which the price of something could differ greatly from its actual value — invariably formed.

Even more remarkably, the researchers discovered a correlation between specific brain activity ...

Negar Sani solved the mystery of the printed diode

2014-07-07

VIDEO:

The video shows how a printed label picks up the radio signal from a telephone making a call, and uses the energy to switch the integrated display. This is only...

Click here for more information.

With an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States of America (PNAS), a thirteen-year-long mystery that has involved a long series of researchers at both Linköping University and Acreo Swedish ICT has finally been solved.

The ...

Neuroeconomists confirm Warren Buffett's wisdom

2014-07-07

Investment magnate Warren Buffett has famously suggested that investors should try to "be fearful when others are greedy and be greedy only when others are fearful."

That turns out to be excellent advice, according to the results of a new study by researchers at Caltech and Virginia Tech that looked at the brain activity and behavior of people trading in experimental markets where price bubbles formed. In such markets, where price far outpaces actual value, it appears that wise traders receive an early warning signal from their brains—a warning that makes them feel uncomfortable ...

Smart and socially adept

2014-07-07

Wanted: Highly skilled individual who is also a team player. In other words, someone who knows his or her stuff and also plays well with others.

Two qualities are particularly essential for success in the workplace: book smarts and social adeptness. The folks who do well tend to demonstrate one or the other. However, according to research conducted by UC Santa Barbara economist Catherine Weinberger, the individuals who reach the highest rungs on the corporate ladder are smart and social. Her findings appear in a recent online issue of the Review of Economics and Statistics.

Weinberger, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Discovery of Neandertal trait in ancient skull raises new questions about human evolutionModern humans emerged from a complex 'labyrinth of biology and peoples,' findings suggest