(Press-News.org) As anybody who has started a campfire by rubbing sticks knows, friction generates heat. Now, computer modeling by NASA scientists shows that friction could be the key to survival for some distant Earth-sized planets traveling in dangerous orbits.

The findings are consistent with observations that Earth-sized planets appear to be very common in other star systems. Although heat can be a destructive force for some planets, the right amount of friction, and therefore heat, can be helpful and perhaps create conditions for habitability.

"We found some unexpected good news for planets in vulnerable orbits," said Wade Henning, a University of Maryland scientist working at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the new study. "It turns out these planets will often experience just enough friction to move them out of harm's way and into safer, more-circular orbits more quickly than previously predicted."

Simulations of young planetary systems indicate that giant planets often upset the orbits of smaller inner worlds. Even if those interactions aren't immediately catastrophic, they can leave a planet in a treacherous eccentric orbit – a very elliptical course that raises the odds of crossing paths with another body, being absorbed by the host star, or getting ejected from the system.

Another potential peril of a highly eccentric orbit is the amount of tidal stress a planet may undergo as it draws very close to its star and then retreats away. Near the star, the gravitational force is powerful enough to deform the planet, while in more distant reaches of the orbit, the planet can ease back into shape. This flexing action produces friction, which generates heat. In extreme cases, tidal stress can produce enough heat to liquefy the planet.

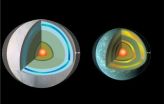

In this new study, available online in the July 1, 2014, issue of the Astrophysical Journal, Henning and his colleague Terry Hurford, a planetary scientist at Goddard, explored the effects of tidal stresses on planets that have multiple layers, such as rocky crust, mantle or iron core.

One conclusion of the study is that some planets could move into a safer orbit about 10 to 100 times faster than previously expected – in as a little as a few hundred thousand years, instead of the more typical rate of several million years. Such planets would be driven close to the point of melting or, at least, would have a nearly melted layer, similar to the one right below Earth's crust. Their interior temperatures could range from moderately warmer than our planet is today up to the point of having modest-sized magma oceans.

The transition to a circular orbit would be speedy because an almost-melted layer would flex easily, generating a lot of friction-induced heat. As the planet threw off that heat, it would lose energy at a fast rate and relax quickly into a circular orbit. (Later, tidal heating would turn off, and the planet's surface could become safe to walk on.)

In contrast, a world that had completely melted would be so fluid that it would produce little friction. Before this study, that is what researchers expected to happen to planets undergoing strong tidal stresses.

Cold, stiff planets tend to resist the tidal stress and release energy very slowly. In fact, Henning and Hurford found that many of them actually generate less friction than previously thought. This may be especially true for planets farther from their stars. If these worlds are not crowded by other bodies, they may be stable in their eccentric orbits for a long time.

"In this case, the longer, non-circular orbits could increase the 'habitable zone,' because the tidal stress will remain an energy source for longer periods of time," said Hurford. "This is great for dim stars or ice worlds with subsurface oceans."

Surprisingly, another way for a terrestrial planet to achieve high amounts of heating is to be covered in a very thick ice shell, similar to an extreme "snowball Earth." Although a sheet of ice is a slippery, low-friction surface, an ice layer thousands of miles thick would be very springy. A shell like this would have just the right properties to respond strongly to tidal stress, generating a lot of heat. (The high pressures inside these planets could prevent all but the topmost layers from turning into liquid water.)

The researchers found that the very responsive layers of ice or almost-melted material could be relatively thin, just a few hundred miles deep in some cases, yet still dominate the global behavior.

The team modeled planets that are the size of Earth and up to two-and-a-half times larger. Henning added that superEarths – planets at the high end of this size range – likely would experience stronger tidal stresses and potentially could benefit more from the resulting friction and heating.

Now that the researchers have shown the importance of the contributions of different layers of a planet, the next step is to investigate how layers of melted material flow and change over time.

INFORMATION:

NASA finds friction from tides could help distant earths survive, and thrive

2014-07-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA MESSENGER and STEREO measurements open new window into high-energy processes on the sun

2014-07-09

Understanding the sun from afar isn't easy. How do you figure out what powers solar flares – the intense bursts of radiation coming from the release of magnetic energy associated with sunspots – when you must rely on observing only the light and particles that make their way to near-Earth's orbit?

One answer: you get closer. NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft -- which orbits Mercury, and so is as close as 28 million miles from the sun versus Earth's 93 million miles -- is near enough to the sun to detect solar neutrons that are created in solar flares. The average lifetime for ...

New recreational travel model to help states stop firewood assisted insect travel

2014-07-09

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, NC, July 9, 2014 – The spread of damaging invasive forest pests is only partially powered by the insects' own wings. People moving firewood for camping can hasten and widen the insects' spread and resulting forest destruction. A new U.S. Forest Service study gives state planners a tool for anticipating the most likely route of human-assisted spread they can use to enhance survey and public education efforts.

The study, "Using a Network Model to Assess Risk of Forest Pest Spread via Recreational Travel," was published July 9 in the journal PLOS ...

CNIO scientists discover that pluripotency factor NANOG is also active in adult organisms

2014-07-09

Scientists from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) have discovered that NANOG, an essential gene for embryonic stem cells, also regulates cell division in stratified epithelia—those that form part of the epidermis of the skin or cover the oesophagus or the vagina—in adult organisms. According to the conclusions of the study, published in the journal Nature Communications, this factor could also play a role in the formation of tumours derived from stratified epithelia of the oesophagus and skin.

The pluripotency factor NANOG is active during just two days ...

No extra mutations in modified stem cells, study finds

2014-07-09

LA JOLLA-The ability to switch out one gene for another in a line of living stem cells has only crossed from science fiction to reality within this decade. As with any new technology, it brings with it both promise--the hope of fixing disease-causing genes in humans, for example--as well as questions and safety concerns. Now, Salk scientists have put one of those concerns to rest: using gene-editing techniques on stem cells doesn't increase the overall occurrence of mutations in the cells. The new results were published July 3 in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

"The ability ...

Hunting gives deer-damaged forests in state parks a shot at recovery

2014-07-09

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Regulated deer hunts in Indiana state parks have helped restore the health of forests suffering from decades of damage caused by overabundant populations of white-tailed deer, a Purdue study shows.

A research team led by Michael Jenkins, associate professor of forest ecology, found that a 17-year-long Indiana Department of Natural Resources policy of organizing hunts in state parks has successfully spurred the regrowth of native tree seedlings, herbs and wildflowers rendered scarce by browsing deer.

Jenkins said that while hunting may be unpopular ...

Protein pushes breast cancer cells to metastasize

2014-07-09

Using an innovative tool that captures heretofore hidden ways that cells are regulated, scientists at Rockefeller University have identified a protein that makes breast cancer cells more likely to metastasize.

What's more, the protein appears to trigger cancer's spread in part by blocking two other proteins that are normally linked to neurodegeneration, a finding that suggests these two disease processes could have unexpected ties.

The study, which appears in the July 10 issue of Nature, points to the possibility of new cancer therapies that target this "master regulator" ...

Not at home on the range

2014-07-09

As climate change shifts the geographic ranges in which animals can be found, concern mounts over the effect it has on their parasites. Does an increased range for a host mean new territory for its parasites as well?

Not necessarily, says a team of UC Santa Barbara scientists, including parasitologists Ryan Hechinger and Armand Kuris. In a study published in the Journal of Biogeography, Hechinger, Kuris and colleagues show that for some species, the opposite may happen: Hosts may actually lose their parasites when the hosts shift or increase their range. Theirs is one ...

New system would give individuals more control over shared digital data

2014-07-09

Cellphone metadata has been in the news quite a bit lately, but the National Security Agency isn't the only organization that collects information about people's online behavior. Newly downloaded cellphone apps routinely ask to access your location information, your address book, or other apps, and of course, websites like Amazon or Netflix track your browsing history in the interest of making personalized recommendations.

At the same time, a host of recent studies have demonstrated that it's shockingly easy to identify unnamed individuals in supposedly "anonymized" data ...

NASA, NOAA satellites help confirm Tropical Storm Fausto as a remnant low

2014-07-09

NOAA's GOES-West and NASA-JAXA's Global Precipitation Measurement or GPM mission satellite helped forecasters at the National Hurricane Center determine that what was once Tropical Storm Fausto is now a remnant area of low pressure in the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Forecaster Beven at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) noted that "satellite imagery, overnight scatterometer data, and a recent GPM satellite microwave overpass indicate that Fausto has degenerated to a trough of low pressure."

On July 9 at 1500 UTC (11 a.m. EDT) Fausto's circulation was no longer apparent ...

Study identifies novel genomic changes in the most common type of lung cancer

2014-07-09

Researchers from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network have identified novel mutations in a well-known cancer-causing pathway in lung adenocarcinoma, the most common subtype of lung cancer. Knowledge of these genomic changes may expand the number of possible therapeutic targets for this disease and potentially identify a greater number of patients with treatable mutations because many potent cancer drugs that target these mutations already exist.

TCGA is jointly funded and managed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research ...