(Press-News.org) Social animals often develop relationships with other group members to reduce aggression and gain access to scarce resources. In wild chacma baboons the strategy for grooming activities shows a certain pattern across the day. The results are just published in the scientific journal Biology Letters.

Grooming between individuals in a group of baboons is not practiced without ulterior motives. To be groomed has hygienic benefits and is stress relieving for the individual, while grooming another individual can provide access to infants, mating opportunities and high quality food by means of tolerance at a patch. This can be used in a strategic manner by trading grooming for one of these commodities as stated by the biological market theory. A new study from Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen and Zoological Society of London shows that such social strategies in chacma baboons vary across the day in a manner where subordinate individuals will gain most from their grooming activities.

"We investigated whether diurnal changes in the value of one commodity, tolerance at shared food patches, lead to diurnal patterns of affiliative interaction, namely grooming. As predicted, we found that, in wild chacma baboons, subordinates were more likely to groom the more dominant individuals earlier in the day, when most foraging activities still lay ahead and the need for tolerance at shared feeding sites was greatest", says MSc biologist Claudia Sick, Section for Ecology and Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen in affiliation with Zoological Society of London.

This study shows that social strategies of baboons can vary across the day and the findings suggest that group-living animals optimize certain elements of their social strategies over short periods of time. It is commonly known that strong social bonds over several years can make an important contribution to the fitness of individuals in animal groups. Therefore one could expect individuals to invest primarily in such long-term relationships. However, studies have shown that relationships also vary over months and weeks in accordance with a biological market. This study's new findings indicate that social strategies may be even more flexible and optimized over even shorter periods that previously appreciated.

These new insights highlight the importance of understanding the full range of time periods over which social strategies may be optimized. Such knowledge is crucial when studying the social behaviour and strategies of group-living animals.

INFORMATION: END

Baboons groom early in the day to get benefits later

2014-07-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A first direct glimpse of photosynthesis in action

2014-07-11

An international team of researchers, including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, has just a reported a major step in understanding photosynthesis, the process by which the Earth first gained and now maintains the oxygen in its atmosphere and which is therefore crucial for all higher forms of life on earth.

The researchers report the first direct visualization of a crucial event in the photosynthetic reaction, namely the step in which a specific protein complex, photosystem II, splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using energy ...

Molecular snapshots of oxygen formation in photosynthesis

2014-07-11

Researchers from Umeå University, Sweden, have explored two different ways that allow unprecedented experimental insights into the reaction sequence leading to the formation of oxygen molecules in photosynthesis. The two studies have been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

"The new knowledge will help improving present day synthetic catalysts for water oxidation, which are key components for building artificial leaf devices for the direct storage of solar energy in fuels like hydrogen, ethanol or methanol," says Johannes Messinger, Professor in ...

3-D technology used to help California condors and other endangered species

2014-07-11

A team including researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research has developed a novel methodology that, for the first time, combines 3-D and advanced range estimator technologies to provide highly detailed data on the range and movements of terrestrial, aquatic, and avian wildlife species. One aspect of the study focused on learning more about the range and movements of the California condor using miniaturized GPS biotelemetry units attached to every condor released into the wild.

"We have been calculating ...

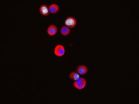

USC stem cell researcher targets the 'seeds' of breast cancer metastasis

2014-07-11

For breast cancer patients, the era of personalized medicine may be just around the corner, thanks to recent advances by USC Stem Cell researcher Min Yu and scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

In a July 11 study in Science, Yu and her colleagues report how they isolated breast cancer cells circulating through the blood streams of six patients. Some of these deadly cancer cells are the "seeds" of metastasis, which travel to and establish secondary tumors in vital organs such as the bone, lungs, liver and brain.

Yu and her colleagues ...

Precipitation, not warming temperatures, may be key in bird adaptation to climate change

2014-07-11

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new model analyzing how birds in western North America will respond to climate change suggests that for most species, regional warming is not as likely to influence population trends as will precipitation changes.

Several past studies have found that temperature increases can push some animal species – including birds – into higher latitudes or higher elevations. Few studies, however, have tackled the role that changes in precipitation may cause, according to Matthew Betts, an Oregon State University ecologist and a principal investigator on the study.

"When ...

Do women perceive other women in red as more sexually receptive?

2014-07-11

Previous research has shown that men perceive the color red on a woman to be a signal of sexual receptivity. Women are more likely to wear a red shirt when they are expecting to meet an attractive man, relative to an unattractive man or a woman. But do women view other women in red as being more sexually receptive? And would that result in a woman guarding her mate against a woman in red? A study published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin sought to answer these questions.

Perceptions of Sexual Receptivity

Nonverbal communication via body language, facial ...

ACL reconstructions may last longer with autografts

2014-07-11

SEATTLE, WA – Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) reconstructions occur more than 200,000 times a year, but the type of material used to create a new ligament may determine how long you stay in the game, say researchers presenting their work today at the Annual Meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society of Sports Medicine (AOSSM).

"Our study results highlight that in a young athletic population, allografts (tissue harvested from a donor) fail more frequently than using autografts (tissue harvested from the patient)," said Craig R. Bottoni, MD, lead author from Tripler ...

New study may identify risk factors for ACL re-injury

2014-07-11

SEATTLE, WA – Re-tearing a repaired knee Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) happens all too frequently, however a recent study being presented today at the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine's (AOSSM) Annual Meeting suggests that identification and patient education regarding modifiable risk factors may minimize the chance of a future ACL tear.

"Our research suggests that a few risk factors such as, age, activity level and type of graft utilized may point to the possibility of re-injury," said lead author, Christopher C. Kaeding, MD of the Ohio State University. ...

Potent spider toxin 'electrocutes' German, not American, cockroaches

2014-07-11

Using spider toxins to study the proteins that let nerve cells send out electrical signals, Johns Hopkins researchers say they have stumbled upon a biological tactic that may offer a new way to protect crops from insect plagues in a safe and environmentally responsible way.

Their finding—that naturally occurring insect toxins can be lethal for one species and harmless for a closely related one—suggests that insecticides can be designed to target specific pests without harming beneficial species like bees. A summary of the research, led by Frank Bosmans, Ph.D., an assistant ...

Blame it on the astrocytes

2014-07-11

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil- In the brains of all vertebrates, information is transmitted through synapses, a mechanism that allows an electric or chemical signal to be passed from one brain cell to another. Chemical synapses, which are the most abundant type of synapse, can be either excitatory or inhibitory. Synapse formation is crucial for learning, memory, perception and cognition, and the balance between excitatory and inhibitory synapses critical for brain function. For instance, every time we learn something, the new information is transformed into memory through synaptic ...