(Press-News.org) A cross-disciplinary team is calling for public discussion about a potential new way to solve longstanding global ecological problems by using an emerging technology called "gene drives." The advance could potentially lead to powerful new ways of combating malaria and other insect-borne diseases, controlling invasive species and promoting sustainable agriculture.

Representing the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Boston University, the Woodrow Wilson Center, and Arizona State University, the team includes scientists working in disciplines ranging from genome engineering to public health and ecology, as well as risk and policy analysis.

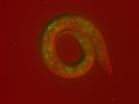

Engineered gene drives are genetic systems that circumvent traditional rules of sexual reproduction and greatly increase the odds that the drive will be passed on to offspring. This enables the spread of specified genetic alterations through targeted wild populations over many generations. They represent a potentially powerful tool to confront regional or global challenges, including control of invasive species and eradication of insect-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue.

The idea is not new, but the Harvard-based researchers have now outlined a technically feasible way to build gene drives that potentially could spread almost any genomic change through populations of sexually reproducing species.

"We all rely on healthy ecosystems and share a responsibility to keep them intact for future generations," said Kevin Esvelt, PhD, Wyss Institute Technology Development Fellow and lead author of two papers published this week. "Given the broad potential of gene drives to address ecological problems, we hope to initiate a transparent, inclusive and informed public discussion—well in advance of any testing—to collectively decide how we might use this technology for the betterment of humanity and the environment."

Following discussion of the technology's widespread implications at an NSF-sponsored workshop organized by the Woodrow Wilson Center and MIT in January 2014, the team wrote two related papers. The first, published in eLife, describes the proposed technical methods of building gene drives in different species, defines their theoretical capabilities and limitations, and outlines possible applications. The second, featured in Science, provides an initial assessment of potential environmental and security effects, an analysis of regulatory coverage and recommendations to ensure responsible development and testing prior to use.

The new technical work in eLife builds upon research by Austin Burt of Imperial College London, who, more than a decade ago, first proposed using a type of gene drive based on cutting DNA to alter populations. The authors note that the versatile gene editing tool called CRISPR, which was recently co-developed by some of the same researchers at Harvard and the Wyss Institute and makes it possible to precisely insert, replace and regulate genes, now makes it feasible to create gene drives that work in many different species.

"Our proposal represents a potentially powerful ecosystem management tool for global sustainability, but one that carries with it new concerns, as with any emerging technology," said Wyss Core Faculty member George Church, PhD, a coauthor on both publications. Church is also a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, and professor of health sciences and technology at Harvard and MIT.

Esvelt noted that the genomic changes made by gene drives should be reversible. The team has outlined in the eLife publication numerous precautionary measures intended to guide the safe and responsible development of gene drives, many of which were not possible with earlier technologies.

"If the public ever considers making use of a gene drive, we will need to develop appropriate safeguards. Ensuring that we have a working reversal drive on hand to quickly undo the proposed genomic change would be one such precaution," he said.

Because the drives can spread traits only over generations, they will be most effective in species that reproduce quickly or can be released in large numbers. For insects, it could take only a couple of years to see a desired change in the population at large, while slower-reproducing organisms would require much longer. Altering human populations is not feasible because it would require many centuries.

Gene drives could strike a powerful blow against malaria by altering mosquito populations so that they can no longer spread the disease, which kills 650,000 people every year and sickens hundreds of millions. They might also be used to rid local environments of invasive species or to pave the way toward more sustainable agriculture by reversing mutations that allow particular weed species, such as horseweed, to resist herbicides that are important for no-till farming.

The innovative nature of gene drives poses regulatory challenges. "Simply put, gene drives do not fit comfortably within existing U.S. regulations and international conventions," said political scientist Kenneth Oye, PhD, author of the Science paper and director of the MIT Program on Emerging Technologies. "For example, animal applications of gene drives would be regulated by the FDA as veterinary medicines. Potential implications of gene drives fall beyond the purview of the lists of bacteriological and viral agents that now define security regimes. We'll need both regulatory reform and public engagement before we can consider beneficial uses. That is why we are excited about getting the conversation on gene drives going early."

"Many different groups and the interested public will need to come together to ensure that gene drives are developed and used responsibly," said James P. Collins, PhD, an evolutionary ecologist at Arizona State University and senior author of the Science paper. Collins was formerly the assistant director for biological sciences at the National Science Foundation.

"Understanding how populations and ecosystems will respond to different alterations and addressing potential security concerns will require sustained multidisciplinary work by teams of biological engineers, ecologists, instrumentation specialists, social scientists and the public," Collins said. "The eLife and Science articles provide a model for the next steps that need to be taken."

INFORMATION:

New potential way to control spread of insect-borne disease

Cross-disciplinary team launches public conversation about new way to manage ecosystems

2014-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

In development, it's all about the timing

2014-07-17

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – Closely related organisms share most of their genes, but these similarities belie major differences in behavior, intelligence, and physical appearance. For example, we share nearly 99% of our genes with chimps, our closest relatives on the great "tree of life." Still, the differences between the two species are unmistakable. If not just genes, what else accounts for the disparities? Scientists are beginning to appreciate that the timing of the events that happen during development plays a decisive role in defining an organism, which may help to ...

Viral relics show cancer's 'footprint' on our evolution

2014-07-17

Viral relics show cancer’s ‘footprint’ on our evolution Cancer has left its ‘footprint’ on our evolution, according to a study which examined how the relics of ancient viruses are preserved in the genomes of 38 mammal species.

Viral relics are evidence of the ancient battles our genes have fought against infection. Occasionally the retroviruses that infect an animal get incorporated into that animal’s genome and sometimes these relics get passed down from generation to generation – termed ‘endogenous retroviruses’ (ERVs). Because ERVs may be copied to other parts of the ...

When is a molecule a molecule?

2014-07-17

Using ultra-short X-ray flashes, an international team of researchers watched electrons jumping between the fragments of exploding molecules. The study reveals up to what distance a charge transfer between the two molecular fragments can occur, marking the limit of the molecular regime. The technique used can show the dynamics of charge transfer in a wide range of molecular systems, as the scientists around Dr. Benjamin Erk and Dr. Daniel Rolles of DESY and Professor Artem Rudenko of Kansas State University report in the scientific journal Science. Such mechanisms play ...

Pitt-led study suggests cystic fibrosis is 2 diseases, 1 doesn't affect lungs

2014-07-17

PITTSBURGH, July 17, 2014 – Cystic fibrosis (CF) could be considered two diseases, one that affects multiple organs including the lungs, and one that doesn't affect the lungs at all, according to a multicenter team led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The research, published online today in PLOS Genetics, showed that nine variants in the gene associated with cystic fibrosis can lead to pancreatitis, sinusitis and male infertility, but leave the lungs unharmed.

People with CF inherit from each parent a severely mutated copy of a gene ...

Scientists find protein-building enzymes have metamorphosed & evolved new functions

2014-07-17

LA JOLLA, CA AND JUPITER, FL—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) and their collaborators have found that ancient enzymes, known for their fundamental role in translating genetic information into proteins, evolved myriad other functions in humans. The surprising discovery highlights an intriguing oddity of protein evolution as well as a potentially valuable new class of therapeutic proteins and therapeutic targets.

"These new protein variants represent a previously unrecognized layer of biology—the ...

A new stable and cost-cutting type of perovskite solar cell

2014-07-17

Perovskite solar cells show tremendous promise in propelling solar power into the marketplace. The cells use a hole-transportation layer, which promotes the efficient movement of electrical current after exposure to sunlight. However, manufacturing the hole-transportation organic materials is very costly and lack long term stability. Publishing in Science, a team of scientists in China, led by Professor Hongwei Han in cooperation with Professor Michael Grätzel at EPFL, have developed a perovskite solar cell that does not use a hole-transporting layer, with 12.8% conversion ...

Scientists complete chromosome-based draft of the wheat genome

2014-07-17

MANHATTAN, Kansas — Several Kansas State University researchers were essential in helping scientists assemble a draft of a genetic blueprint of bread wheat, also known as common wheat. The food plant is grown on more than 531 million acres around the world and produces nearly 700 million tons of food each year.

The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium, which also includes faculty at Kansas State University, recently published a chromosome-based draft sequence of wheat's genetic code, which is called a genome. "A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid ...

Ultrafast X-ray laser sheds new light on fundamental ultrafast dynamics

2014-07-17

MANHATTAN, Kansas — Ultrafast X-ray laser research led by Kansas State University has provided scientists with a snapshot of a fundamental molecular phenomenon. The finding sheds new light on microscopic electron motion in molecules.

Artem Rudenko, assistant professor of physics and a member of the university's James R. Macdonald Laboratory; Daniel Rolles, currently a junior research group leader at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron in Hamburg, Germany, who will be joining the university's physics department in January 2015; and an international group of collaborators ...

No evidence that California cellphone ban decreased accidents, says Colarado University Boulder researcher

2014-07-17

In a recent study, a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder found no evidence that a California ban on using hand-held cellphones while driving decreased the number of traffic accidents in the state in the first six months following the ban.

The findings, published in the journal Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, are surprising given prior research that suggests driving while using a cellphone is risky. For example, past laboratory studies have shown that people who talk on a cellphone while using driving simulators are as impaired as people ...

Peering into giant planets from in and out of this world

2014-07-17

Lawrence Livermore scientists for the first time have experimentally re-created the conditions that exist deep inside giant planets, such as Jupiter, Uranus and many of the planets recently discovered outside our solar system.

Researchers can now re-create and accurately measure material properties that control how these planets evolve over time, information essential for understanding how these massive objects form. This study focused on carbon, the fourth most abundant element in the cosmos (after hydrogen, helium and oxygen), which has an important role in many types ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] New potential way to control spread of insect-borne diseaseCross-disciplinary team launches public conversation about new way to manage ecosystems