(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass-- Researchers at MIT and in Saudi Arabia have developed a new way of making surfaces that can actively control how fluids or particles move across them. The work might enable new kinds of biomedical or microfluidic devices, or solar panels that could automatically clean themselves of dust and grit.

"Most surfaces are passive," says Kripa Varanasi, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, and senior author of a paper describing the new system in the journal Applied Physics Letters. "They rely on gravity, or other forces, to move fluids or particles."

Varanasi's team decided to use external fields, such as magnetic fields, to make surfaces active, exerting precise control over the behavior of particles or droplets moving over them.

The system makes use of a microtextured surface, with bumps or ridges just a few micrometers across, that is then impregnated with a fluid that can be manipulated — for example, an oil infused with tiny magnetic particles, or ferrofluid, which can be pushed and pulled by applying a magnetic field to the surface. When droplets of water or tiny particles are placed on the surface, a thin coating of the fluid covers them, forming a magnetic cloak.

The thin magnetized cloak can then actually pull the droplet or particle along as the layer itself is drawn magnetically across the surface. Tiny ferromagnetic particles, approximately 10 nanometers in diameter, in the ferrofluid could allow precision control when it's needed — such as in a microfluidic device used to test biological or chemical samples by mixing them with a variety of reagents. Unlike the fixed channels of conventional microfluidics, such surfaces could have "virtual" channels that could be reconfigured at will.

While other researchers have developed systems that use magnetism to move particles or fluids, these require the material being moved to be magnetic, and very strong magnetic fields to move them around. The new system, which produces a superslippery surface that lets fluids and particles slide around with virtually no friction, needs much less force to move these materials. "This allows us to attain high velocities with small applied forces," says MIT graduate student Karim Khalil, the paper's lead author.

The new approach, he says, could be useful for a range of applications: For example, solar panels and the mirrors used in solar-concentrating systems can quickly lose a significant percentage of their efficiency when dust, moisture, or other materials accumulate on their surfaces. But if coated with such an active surface material, a brief magnetic pulse could be used to sweep the material away.

"Fouling is a big problem on such mirrors," Varanasi says. "The data shows a loss of almost 1 percent of efficiency per week."

But at present, even in desert locations, the only way to counter this fouling is to hose the arrays down, a labor- and water-intensive method. The new approach, the researchers say, could lead to systems that make the cleaning process automatic and water-free.

"In the desert environment, dust is present on a daily basis," says co-author Numan Abu-Dheir of the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) in Saudi Arabia. "The issue of dust basically makes the use of solar panels to be less efficient than in North America or Europe. We need a way to reduce the dust accumulation."

One advantage of the new active-surface system is its effectiveness on a wide range of surface contaminants: "You want to be able to propel dust or liquid, many materials on surfaces, whatever their properties," Varanasi says.

MIT postdoc Seyed Mahmoudi, a co-author of the paper, notes that electric fields cannot penetrate into conductive fluids, such as biological fluids, so conventional systems wouldn't be able to manipulate them. But with this system, he says, "electrical conductivity is not important."

In addition, this approach gives a great deal of control over how material moves. "Active fields — such as electric, magnetic, and acoustic fields — have been used to manipulate materials," Khalil says. "But rarely have you seen the surface itself interact actively with the material on it," he says, which allows much greater precision.

While this initial demonstration used a magnetic fluid, the team says the same principle could be applied using other forces to manipulate the material, such as electric fields or differences in temperature.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the MIT-KFUPM Center for Clean Water and Clean Energy.

'Active' surfaces control what's on them

Researchers develop treated surfaces that can actively control how fluids or particles move

2014-08-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Wetting' a battery's appetite for renewable energy storage

2014-08-01

RICHLAND, Wash. – Sun, wind and other renewable energy sources could make up a larger portion of the electricity America consumes if better batteries could be built to store the intermittent energy for cloudy, windless days. Now a new material could allow more utilities to store large amounts of renewable energy and make the nation's power system more reliable and resilient.

A paper published today in Nature Communications describes an electrode made of a liquid metal alloy that enables sodium-beta batteries to operate at significantly lower temperatures. The new electrode ...

NUS study shows effectiveness of common anti-malarial drug in controlling asthma

2014-08-01

Asthmatic patients may soon have a more effective way to control the condition, thanks to a new pharmacological discovery by researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The team, led by Associate Professor Fred Wong from the Department of Pharmacology at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, together with Dr Eugene Ho Wanxing, a recent PhD graduate from the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at NUS, discovered that artesunate, a common herbal-based anti-malarial drug, can be used to control asthma, with better treatment outcomes than other drugs ...

Preterm children do not have an increased risk for dyscalculia

2014-08-01

Preterm children do not suffer from dyscalculia more often than healthy full term children. Dr Julia Jäkel, a developmental psychologist from Bochum, and her colleague Prof Dr Dieter Wolke from the University of Warwick, UK proved this thesis to be true in their analyses – thus refuting previous scientific studies. Unlike other studies, the researchers took the children's IQ into consideration.

Dyscalculia in preterm children often impossible to diagnose

Preterm children often have cognitive deficits; they find solving complex tasks particularly difficult. However, ...

Scientists solve 2000-year-old mystery of the binding media in China's polychrome Terracotta Army

2014-08-01

Even as he conquered rival kingdoms to create the first united Chinese empire in 221 B.C., China's First Emperor Qin Shihuang ordered the building of a glorious underground palace complex, mirroring his imperial capital near present-day Xi'an, that would last for an eternity.

To protect his underworld palaces, the First Emperor issued instructions that his imperial guard be replicated, down to the finest details, in red-brown terracotta clay, poised to do battle. Thousands of these imperial guards were initially discovered in 1974; some contained patches of pigment that ...

Taking the guesswork out of cancer therapy

2014-08-01

Researchers and doctors at the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (IBN), Singapore General Hospital (SGH) and National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) have co-developed the first molecular test kit that can predict treatment and survival outcomes in kidney cancer patients. This breakthrough was recently reported in European Urology, the world's top urology journal.

According to IBN Executive Director Professor Jackie Y. Ying, "By combining our expertise in molecular diagnostics and cancer research, we have developed the first genetic test to help doctors prescribe ...

Georgia Tech jailbreaks iOS 7.1.2

2014-08-01

Security researchers at the Georgia Tech Information Security Center (GTISC) have discovered a way to jailbreak current generation Apple iOS devices (e.g., iPhones and iPads) running the latest iOS software.

The jailbreak, which enables circumvention of Apple's closed platform, was discovered by analyzing previously patched vulnerabilities with incomplete fixes.

It shows that quick workarounds mitigating only a subset of a multi-step attack leave these devices vulnerable to exploitation. Patching all vulnerabilities for a modern, complex software system (i.e., Windows ...

Symbiotic survival

2014-08-01

Boulder, Colo., USA – One of the most diverse families in the ocean today -- marine bivalve mollusks known as Lucinidae (or lucinids) -- originated more than 400 million years ago in the Silurian period, with adaptations and life habits like those of its modern members. This Geology study by Steven Stanley of the University of Hawaii, published online on 25 July 2014, tracks the remarkable evolutionary expansion of the lucinids through significant symbiotic relationships.

At is origin, the Lucinidae family remained at very low diversity until the rise of mangroves and ...

Companion planets can increase old worlds' chance at life

2014-08-01

Having a companion in old age is good for people — and, it turns out, might extend the chance for life on certain Earth-sized planets in the cosmos as well.

Planets cool as they age. Over time their molten cores solidify and inner heat-generating activity dwindles, becoming less able to keep the world habitable by regulating carbon dioxide to prevent runaway heating or cooling.

But astronomers at the University of Washington and the University of Arizona have found that for certain planets about the size of our own, the gravitational pull of an outer companion planet ...

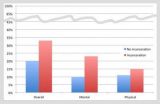

Jailed family member increases risks for kids' adult health

2014-08-01

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — New research shows that people who grew up in a household where a member was incarcerated have a 16-percent greater risk of experiencing poor health quality than adults who did not have a family member sent to prison. The finding, which accounted for other forms of childhood adversity, suggests that the nation's high rate of imprisonment may be independently imparting enduring physical and mental health difficulties in some families.

"These people were children when this happened, and it was a significant disruptive event," said Annie ...

2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: Cardiovascular assessment and management

2014-08-01

The publication of the new joint ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management introduces a number of recommendations in the field. Among other topics, the Guidelines include updated information on the use of clinical indices and biomarkers in risk assessment, and the use of novel anticoagulants, statins, aspirin and beta-blockers in risk mitigation.

Worldwide, non-cardiac surgery is associated with an average overall complication rate of between 7% and 11% and a mortality rate between 0.8% and 1.5%, depending on safety precautions. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

[Press-News.org] 'Active' surfaces control what's on themResearchers develop treated surfaces that can actively control how fluids or particles move