(Press-News.org) Building upon previous research, scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Veteran's Affairs San Diego Healthcare System report that neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) and grafted into rats after a spinal cord injury produced cells with tens of thousands of axons extending virtually the entire length of the animals' central nervous system.

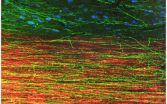

Writing in the August 7 early online edition of Neuron, lead scientist Paul Lu, PhD, of the UC San Diego Department of Neurosciences and colleagues said the human iPSC-derived axons extended through the white matter of the injury sites, frequently penetrating adjacent gray matter to form synapses with rat neurons. Similarly, rat motor axons pierced the human iPSC grafts to form their own synapses.

The iPSCs used were developed from a healthy 86-year-old human male.

"These findings indicate that intrinsic neuronal mechanisms readily overcome the barriers created by a spinal cord injury to extend many axons over very long distances, and that these capabilities persist even in neurons reprogrammed from very aged human cells," said senior author Mark Tuszynski, MD, PhD, professor of Neurosciences and director of the UC San Diego Center for Neural Repair.

For several years, Tuszynski and colleagues have been steadily chipping away at the notion that a spinal cord injury necessarily results in permanent dysfunction and paralysis. Earlier work has shown that grafted stem cells reprogrammed to become neurons can, in fact, form new, functional circuits across an injury site, with the treated animals experiencing some restored ability to move affected limbs. The new findings underscore the potential of iPSC-based therapy and suggest a host of new studies and questions to be asked, such as whether axons can be guided and how will they develop, function and mature over longer periods of time.

While neural stem cell therapies are already advancing to clinical trials, this research raises cautionary notes about moving to human therapy too quickly, said Tuszynski.

"The enormous outgrowth of axons to many regions of the spinal cord and even deeply into the brain raises questions of possible harmful side effects if axons are mistargeted. We also need to learn if the new connections formed by axons are stable over time, and if implanted human neural stem cells are maturing on a human time frame – months to years – or more rapidly. If maturity is reached on a human time frame, it could take months to years to observe functional benefits or problems in human clinical trials."

In the latest work, Lu, Tuszynski and colleagues converted skin cells from a healthy 86-year-old man into iPSCs, which possess the ability to become almost any kind of cell. The iPSCs were then reprogrammed to become neurons in collaboration with the laboratory of Larry Goldstein, PhD, director of the UC San Diego Sanford Stem Cell Clinical Center. The new human neurons were subsequently embedded in a matrix containing growth factors and grafted into two-week-old spinal cord injuries in rats.

Three months later, researchers examined the post-transplantation injury sites. They found biomarkers indicating the presence of mature neurons and extensive axonal growth across long distances in the rats' spinal cords, even extending into the brain. The axons traversed wound tissues to penetrate and connect with existing rat neurons. Similarly, rat neurons extended axons into the grafted material and cells. The transplants produced no detectable tumors.

While numerous connections were formed between the implanted human cells and rat cells, functional recovery was not found. However, Lu noted that tests assessed the rats' skilled use of the hand. Simpler assays of leg movement could still show benefit. Also, several iPSC grafts contained scars that may have blocked beneficial effects of new connections. Continuing research seeks to optimize transplantation methods to eliminate scar formation.

Tuszynski said he and his team are attempting to identify the most promising neural stem cell type for repairing spinal cord injuries. They are testing iPSCs, embryonic stem cell-derived cells and other stem cell types.

"Ninety-five percent of human clinical trials fail. We are trying to do as much as we possibly can to identify the best way of translating neural stem cell therapies for spinal cord injury to patients. It's easy to forge ahead with incomplete information, but the risk of doing so is greater likelihood of another failed clinical trial. We want to determine as best we can the optimal cell type and best method for human translation so that we can move ahead rationally and, with some luck, successfully."

INFORMATION:Co-authors include Grace Woodruff, Yaozhi Wang, Lori Graham, Matt Hunt, Di Wu, Eileen Boehle, Ruhel Ahmad, Gunnar Poplawski and John Brock, all of UC San Diego.

Funding support for this research came, in part, from the Veterans Administration, the National Institutes of Health (grants NS09881 and EB014986), the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Dramatic growth of grafted stem cells in rat spinal cord injuries

Reprogrammed human neurons extend axons almost entire length of central nervous system

2014-08-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Human skin cells reprogrammed as neurons regrow in rats with spinal cord injuries

2014-08-07

While neurons normally fail to regenerate after spinal cord injuries, neurons formed from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that were grafted into rats with such injuries displayed remarkable growth throughout the length of the animals' central nervous system. What's more, the iPSCs were derived from skin cells taken from an 86-year-old man. The results, described in the Cell Press journal Neuron, could open up new possibilities in stimulating neuron growth in humans with spinal cord injuries

"These findings indicate that intrinsic neuronal mechanisms readily ...

Cancer study reveals powerful new system for classifying tumors

2014-08-07

Cancers are classified primarily on the basis of where in the body the disease originates, as in lung cancer or breast cancer. According to a new study, however, one in ten cancer patients would be classified differently using a new classification system based on molecular subtypes instead of the current tissue-of-origin system. This reclassification could lead to different therapeutic options for those patients, scientists reported in a paper published August 7 in Cell.

"It's only ten percent that were classified differently, but it matters a lot if you're one of those ...

Largest cancer genomic study proposes 'disruptive' new system to reclassify tumors

2014-08-07

Novato, California: Researchers with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have analyzed more than 3500 tumors on multiple genomic technology platforms, revealing a new approach to classifying cancers. This largest-of-its-kind study, published online August 7th in Cell featured major contributions by Buck faculty Christopher Benz, MD and Senior Staff Scientist Christina Yau, PhD.

TCGA scientists analyzed the DNA, RNA and protein from 12 different tumor types using six different TCGA "platform technologies" to see how the different tumor types compare to each other. The study ...

University of Minnesota research finds key piece to cancer cell survival puzzle

2014-08-07

An international team led by Eric A. Hendrickson of the University of Minnesota and Duncan Baird of Cardiff University has solved a key mystery in cancer research: What allows some malignant cells to circumvent the normal process of cell death that occurs when chromosomes get too old to maintain themselves properly?

Researchers have long known that chromosomal defects that occur as cells repeatedly divide over time are linked to the onset of cancer. Now, Hendrickson, Baird and colleagues have identified a specific gene that human cells require in order to survive these ...

Notch developmental pathway regulates fear memory formation

2014-08-07

Nature is thrifty. The same signals that embryonic cells use to decide whether to become nerves, skin or bone come into play again when adult animals are learning whether to become afraid.

Researchers at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, have learned that the molecule Notch, critical in many processes during embryonic development, is also involved in fear memory formation. Understanding fear memory formation is critical to developing more effective treatments and preventions for anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The ...

Scientists uncover stem cell behavior of human bowel for the first time

2014-08-07

For the first time, scientists have uncovered new information on how stem cells in the human bowel behave, revealing vital clues about the earliest stages in bowel cancer development and how we may begin to prevent it.

The study, led by Queen May University of London (QMUL) and published today in the journal Cell Reports, discovered how many stem cells exist within the human bowel and how they behave and evolve over time. It was revealed that within a healthy bowel, stem cells are in constant competition with each other for survival and only a certain number of stem ...

Cancer categories recast in largest-ever genomic study

2014-08-07

New research partly led by UC San Francisco-affiliated scientists suggests that one in 10 cancer patients would be more accurately diagnosed if their tumors were defined by cellular and molecular criteria rather than by the tissues in which they originated, and that this information, in turn, could lead to more appropriate treatments.

In the largest study of its kind to date, scientists analyzed molecular and genetic characteristics of more than 3,500 tumor samples of 12 different cancer types using multiple genomic technology platforms.

Cancers traditionally have ...

Scientists uncover key piece to cancer cell survival puzzle

2014-08-07

A chance meeting between two leading UK and US scientists could have finally helped solve a key mystery in cancer research.

Scientists have long known that chromosomal defects occur as cells repeatedly divide. Over time, these defects are linked to the onset of cancer.

Now, Professor Duncan Baird and his team from Cardiff University working in collaboration with Eric A. Hendrickson from the University of Minnesota, have identified a specific gene that human cells require in order to survive these types of defects.

"We have found a gene that appears to be crucial ...

Regulations needed to identify potentially invasive biofuel crops

2014-08-07

URBANA, Ill. – If the hottest new plant grown as a biofuel crop is approved based solely on its greenhouse gas emission profile, its potential as the next invasive species may not be discovered until it's too late. In response to this need to prevent such invasions, researchers at the University of Illinois have developed both a set of regulatory definitions and provisions and a list of 49 low-risk biofuel plants from which growers can choose.

Lauren Quinn, an invasive plant ecologist at U of I's Energy Biosciences Institute, recognized that most of the news about invasive ...

Peer-reviewed paper says all ivory markets must close

2014-08-07

NEW YORK (August 7, 2014) – The message is simple: to save elephants, all ivory markets must close and all ivory stockpiles must be destroyed, according to a new peer-reviewed paper by the Wildlife Conservation Society. The paper says that corruption, organized crime, and a lack of enforcement make any legal trade of ivory a major factor contributing to the demise of Africa's elephants.

Appearing in the August 7th online edition of the journal Conservation Biology, the paper says that if we are to conserve significant wild populations of elephants across all regions ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

New-onset nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and initiators of semaglutide in US veterans with type 2 diabetes

Availability of higher-level neonatal care in rural and urban US hospitals

Researchers identify brain circuit and cells that link prior experiences to appetite

Frog love songs and the sounds of climate change

Hunter-gatherers northwestern Europe adopted farming from migrant women, study reveals

Light-based sensor detects early molecular signs of cancer in the blood

3D MIR technique guides precision treatment of kids’ heart conditions

Which childhood abuse survivors are at elevated risk of depression? New study provides important clues

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

Towards unlocking the full potential of sodium- and potassium-ion batteries

UC Irvine-led team creates first cell type-specific gene regulatory maps for Alzheimer’s disease

Unraveling the mystery of why some cancer treatments stop working

From polls to public policy: how artificial intelligence is distorting online research

Climate policy must consider cross-border pollution “exchanges” to address inequality and achieve health benefits, research finds

What drives a mysterious sodium pump?

Study reveals new cellular mechanisms that allow the most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia to persist in the heart

Scientists discover new gatekeeper cell in the brain

High blood pressure: trained laypeople improve healthcare in rural Africa

Pitt research reveals protective key that may curb insulin-resistance and prevent diabetes

Queen Mary research results in changes to NHS guidelines

Sleep‑aligned fasting improves key heart and blood‑sugar markers

Releasing pollack at depth could benefit their long-term survival, study suggests

[Press-News.org] Dramatic growth of grafted stem cells in rat spinal cord injuriesReprogrammed human neurons extend axons almost entire length of central nervous system