(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — A multi-institutional team has resolved a long-unanswered question about how two of the world's most common substances interact.

In a paper published recently in the journal Nature Communications, Manos Mavrikakis, professor of chemical and biological engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and his collaborators report fundamental discoveries about how water reacts with metal oxides. The paper opens doors for greater understanding and control of chemical reactions in fields ranging from catalysis to geochemistry and atmospheric chemistry.

"These metal oxide materials are everywhere, and water is everywhere," Mavrikakis says. "It would be nice to see how something so abundant as water interacts with materials that are accelerating chemical reactions."

These reactions play a huge role in the catalysis-driven creation of common chemical platforms such as methanol, which is produced on the order of 10 million tons per year as raw material for chemicals production and for uses like fuel. "Ninety percent of all catalytic processes use metal oxides as a support," Mavrikakis says. "Therefore, all of the reactions including water as an impurity or reactant or product would be affected by the insights developed."

Chemists understand how water interacts with many non-oxide metals, which are very homogeneous. Metal oxides are trickier: an occasional oxygen atom is missing, causing what Mavrikakis calls "oxygen defects." When water meets with one of those defects, it forms two adjacent hydroxyls — a stable compound comprised of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom.

Mavrikakis, assistant scientist Guowen Peng and Ph.D. student Carrie Farberow, along with researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark and Lund University in Sweden, investigated how hydroxyls affect water molecules around them, and how that differs from water molecules contacting a pristine metal oxide surface.

The Aarhus researchers generated data on the reactions using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). The Wisconsin researchers then subjected the STM images to quantum mechanical analysis that decoded the resulting chemical structures, defining which atom is which. "If you don't have the component of the work that we provided, there is no way that you can tell from STM alone what the atomic-scale structure of the water is when absorbed on various surfaces" Mavrikakis says.

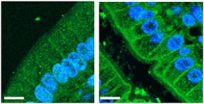

The project yielded two dramatically different pictures of water-metal oxide reactions.

"On a smooth surface, you form amorphous networks of water molecules, whereas on a hydroxylated surface, there are much more structured, well-ordered domains of water molecules," Mavrikakis says.

In the latter case, the researchers realized that hydroxyl behaves as a sort of anchor, setting the template for a tidy hexameric ring of water molecules attracted to the metal's surface.

Mavrikakis' next step is to examine how these differing structures react with other molecules, and to use the research to improve catalysis. He sees many possibilities outside his own field.

"Maybe others might be inspired and look at the geochemistry or atmospheric chemistry implications, such as how these water cluster structures on atmospheric dust nanoparticles could affect cloud formation, rain and acid rain," Mavrikakis says.

Other researchers might also look at whether other molecules exhibit similar behavior when they come into contact with metal oxides, he adds.

"It opens the doors to using hydrogen bonds to make surfaces hydrophilic, or attracted to water, and to (template) these surfaces for the selective absorption of other molecules possessing fundamental similarities to water," Mavrikakis says. "Because catalysis is at the heart of engineering chemical reactions, this is also very fundamental for atomic-scale chemical reaction engineering."

While the research fills part of the foundation of chemistry, it also owes a great deal to state-of-the-art research technology.

"The size and nature of the calculations we had to do probably were not feasible until maybe four or five years ago, and the spatial and temporal resolution of scanning tunneling microscopy was not there," Mavrikakis says. "So it's advances in the methods that allow for this new information to be born."

INFORMATION:

Funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research supported the UW research. Co-authors of the paper include Lindsay R. Merte of Aarhus and Lund and Aarhus researchers Ralf Bechstein, Felix Reiboldt, Helene Zeuthen, Jan Knudsen, Erik Laegsgaard, Stefan Wendt and Flemming Besenbacher.

Scott Gordon

gordon@engr.wisc.edu

608-265-8592

Water's reaction with metal oxides opens doors for researchers

2014-08-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Editing HPV's genes to kill cervical cancer cells

2014-08-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- Researchers have hijacked a defense system normally used by bacteria to fend off viral infections and redirected it against the human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus that causes cervical, head and neck, and other cancers.

Using the genome editing tool known as CRISPR, the Duke University researchers were able to selectively destroy two viral genes responsible for the growth and survival of cervical carcinoma cells, causing the cancer cells to self-destruct.

The findings, appearing online August 7 in the Journal of Virology, give credence to an approach ...

UK study shows promise for new nerve repair technique

2014-08-08

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Aug. 8, 2014) – A multicenter study including University of Kentucky researchers found that a new nerve repair technique yields better results and fewer side effects than other existing techniques.

Traumatic nerve injuries are common, and when nerves are severed, they do not heal on their own and must be repaired surgically. Injuries that are not clean-cut – such as saw injuries, farm equipment injuries, and gunshot wounds – may result in a gap in the nerve.

To fill these gaps, surgeons have traditionally used two methods: a nerve autograft (bridging ...

Ancient shellfish remains rewrite 10,000-year history of El Nino cycles

2014-08-08

The planet's largest and most powerful driver of climate changes from one year to the next, the El Niño Southern Oscillation in the tropical Pacific Ocean, was widely thought to have been weaker in ancient times because of a different configuration of the Earth's orbit. But scientists analyzing 25-foot piles of ancient shells have found that the El Niños 10,000 years ago were as strong and frequent as the ones we experience today.

The results, from the University of Washington and University of Montpellier, question how well computer models can reproduce historical El ...

Kessler Foundation scientists confirm effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation in MS

2014-08-08

WEST ORANGE, NJ August 8, 2014. Kessler Foundation researchers published long-term followup results of their MEMREHAB trial, which show that in individuals with MS, patterns of brain activity associated with learning were maintained at 6 months post training. The article, A pilot study examining functional brain activity 6 months after memory retraining in MS: the MEMREHAB trial, was published online ahead of print on June 14 by Brain Imaging and Behavior (doi: 10.1007/s11682-014-9309-9). The article appeared in the Neuroimaging and Rehabilitation Special Issue. The authors ...

Photo editing algorithm changes weather, seasons automatically

2014-08-08

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — We may not be able control the weather outside, but thanks to a new algorithm being developed by Brown University computer scientists, we can control it in photographs.

The new program enables users to change a suite of "transient attributes" of outdoor photos — the weather, time of day, season, and other features — with simple, natural language commands. To make a sunny photo rainy, for example, just input a photo and type, "more rain." A picture taken in July can be made to look a bit more January simply by typing "more winter." ...

Natural light in office boosts health

2014-08-08

CHICAGO -- Office workers with more light exposure at the office had longer sleep duration, better sleep quality, more physical activity and better quality of life compared to office workers with less light exposure in the workplace, reports a new study from Northwestern Medicine and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The study highlights the importance of exposure to natural light to employee health and the priority architectural designs of office environments should place on natural daylight exposure for workers, the study authors said.

Employees with ...

New culprit identified in metabolic syndrome

2014-08-08

A new study suggests uric acid may play a role in causing metabolic syndrome, a cluster of risk factors that increases the risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Uric acid is a normal waste product removed from the body by the kidneys and intestines and released in urine and stool. Elevated levels of uric acid are known to cause gout, an accumulation of the acid in the joints. High levels also are associated with the markers of metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by obesity, high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar and high cholesterol. But it has been unclear ...

Musical training offsets some academic achievement gaps, research says

2014-08-08

WASHINGTON -- Learning to play a musical instrument or to sing can help disadvantaged children strengthen their reading and language skills, according to research presented at the American Psychological Association's 122nd Annual Convention.

The findings, which involved hundreds of kids participating in musical training programs in Chicago and Los Angeles public schools, highlight the role learning music can have on the brains of youth in impoverished areas, according to presenter Nina Kraus, PhD, a neurobiologist at Northwestern University.

"Research has shown that ...

Disney Research leads development of tool to design inflatable characters and structures

2014-08-08

The air pressure that makes inflatable parade floats, foil balloons and even inflatable buildings easy to deploy and cost effective can be challenging to designers of those same inflatables due to limitations in today's fabrication process, but a new interactive computational tool enables even non-experts to create intricate inflatable structures.

Developed by a team from Disney Research Zurich, ETH Zurich and Columbia University, the method reverse-engineers the physics of inflation as the designer sketches the shape of the structure and the placement of seams. As a ...

Disney Research process designs tops and yo-yos with stable spins despite asymmetric shapes

2014-08-08

Tops and yo-yos are among the oldest types of playthings but researchers at Disney Research Zurich and ETH Zurich have given them a new spin with an algorithm that makes it easier to design these toys so that they have asymmetric shapes.

The algorithm can take a 3D model of an object and, within less than a minute, calculate how mass can be distributed within the object to enable a stable spin around a desired axis. Sometimes, adding voids within the object is sufficient to provide stability; in other cases, the object's shape might need to be altered a bit or a heavier ...