(Press-News.org) Scientists have discovered a new form of dystrophin, a protein critical to normal muscle function, and identified the genetic mechanism responsible for its production. Studies of the new protein isoform, published online Aug. 10 in Nature Medicine and led by a team in The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, suggest it may offer a novel therapeutic approach for some patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a debilitating neuromuscular condition that usually leaves patients unable to walk on their own by age 12.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, is caused by mutations in the gene that encodes dystrophin, which plays a role in stabilizing the membrane of muscle fibers. Without sufficient quantities of the protein, muscle fibers are particularly susceptible to injury during contraction. Over time, the muscle degenerates and muscle fibers are slowly replaced by fat and scar tissue. Many different types of mutations can lead to DMD, some of which block dystrophin production altogether and others that result in a protein that doesn't function normally.

In 2009, a team led by Kevin Flanigan, MD, a principal investigator in the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children's, published two studies describing patients whose genetic mutation was located in a exon 1, at the beginning of the gene. This mutation should have made natural production of functioning dystrophin impossible, resulting in severe disease. However, the patients had only minimal symptoms and relatives carrying the same mutations were identified who were walking well into their 70s. Muscle biopsies revealed that, despite the genetic mutations, the patients were producing significant amounts of a slight smaller yet functioning dystrophin. In the 2009 studies, Dr. Flanigan's group demonstrated that translation of this dystrophin did not begin in exon 1, as usual, but instead began later in the gene in exon 6, although the mechanism controlling this alternate translation remained unknown.

In their latest study, Dr. Flanigan's team has found the explanation. In order to utilize the protein-building instructions they carry, exons are first transcribed into a final genetic blueprint called messenger RNA. Under normal conditions, the messenger RNA is marked at its very beginning by a special molecular cap that is critical for recruiting ribosomes, the cellular structures responsible for translation of the gene into a protein. Most cases of DMD are due to mutations that interrupt the translational activity of ribosomes.

In explaining the mild symptoms seen in many patients with mutations in the first exons of the dystrophin gene — including the group of patients they first described in 2009 — the researchers have now demonstrated that dystrophin can be produced by an alternate cellular mechanism in which capping of the messenger RNA is not required. This newly described mechanism makes use of an internal ribosome entry site, or IRES, found within exon 5 in the dystrophin gene, allowing initiation of protein translation within exon 6 that can then proceed in the normal fashion along the rest of the gene.

"This alternate translational control element is encoded within the dystrophin gene itself, in a region of the gene that evolution has highly conserved," Dr. Flanigan said. "This suggests that the dystrophin protein that results from its activation plays an important but as of yet unknown role in cell function — perhaps when muscle is under cell stress, one of the conditions under which IRES elements are typically activated."

Although clinical trials are currently investigating drugs to treat the more common gene mutations found in the middle of the dystrophin gene, no current therapies are specifically directed toward the approximately 6 percent of patients with mutations affecting the first four exons. Although many of these patients have relatively mild disease, many others have much more severe symptoms. If scientists could figure out a way to activate IRES in those patients, they may be able to produce enough dystrophin to lessen muscle degeneration, Dr. Flanigan said.

To study that possibility, his team is developing different approaches to trigger the IRES, using a new DMD mouse model they have developed. One of these approaches, called exon skipping, is based on the removal of an exon early in the gene in order to mimic the IRES-activating mutations found in minimally affected patients.

"Rather than intending this as a personalized therapy, we are developing this as a tool that could be used for all patients harboring a mutation within the first few exons of dystrophin," said Nicolas Wein, PhD, lead author of the new study and a postdoctoral scientist in the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children's. "Using this approach, we have already shown that we are able to restore running ability in our new mouse model of DMD. We hope to translate this into clinical trials in DMD patients in the future."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and the nonprofit organization CureDuchenne.

Discovery of new form of dystrophin protein could lead to therapy for some DMD patients

2014-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists unlock key to blood vessel formation

2014-08-10

Scientists from the University of Leeds have discovered a gene that plays a vital role in blood vessel formation, research which adds to our knowledge of how early life develops.

The discovery could also lead to greater understanding of how to treat cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Professor David Beech, of the School of Medicine at the University of Leeds, who led the research, said: "Blood vessel networks are not already pre-constructed but emerge rather like a river system. Vessels do not develop until the blood is already flowing and they are created in response ...

Newly discovered heart molecule could lead to effective treatment for heart failure

2014-08-10

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have discovered a previously unknown cardiac molecule that could provide a key to treating, and preventing, heart failure.

The newly discovered molecule provides the heart with a tool to block a protein that orchestrates genetic disruptions when the heart is subjected to stress, such as high blood pressure.

When the research team, led by Ching-Pin Chang, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of medicine at the Indiana University School of Medicine, restored levels of the newly discovered molecule in mice experiencing heart failure, the progression ...

Bioengineers: Matrix stiffness is an essential tool in stem cell differentiation

2014-08-10

Bioengineers at the University of California, San Diego have proven that when it comes to guiding stem cells into a specific cell type, the stiffness of the extracellular matrix used to culture them really does matter. When placed in a dish of a very stiff material, or hydrogel, most stem cells become bone-like cells. By comparison, soft materials tend to steer stem cells into soft tissues such as neurons and fat cells. The research team, led by bioengineering professor Adam Engler, also found that a protein binding the stem cell to the hydrogel is not a factor in the differentiation ...

Pairing old technologies with new for next generation electronic devices

2014-08-10

UCL scientists have discovered a new method to efficiently generate and control currents based on the magnetic nature of electrons in semi-conducting materials, offering a radical way to develop a new generation of electronic devices.

One promising approach to developing new technologies is to exploit the electron's tiny magnetic moment, or 'spin'. Electrons have two properties – charge and spin – and although current technologies use charge, it is thought that spin-based technologies have the potential to outperform the 'charge'-based technology of semiconductors for ...

Physicists create water tractor beam

2014-08-10

VIDEO:

Physicists at the Australian National University have created a tractor beam in water. Using a simple wave generator they can create water currents which could be used to confine oil...

Click here for more information.

Physicists at The Australian National University (ANU) have created a tractor beam on water, providing a radical new technique that could confine oil spills, manipulate floating objects or explain rips at the beach.

The group, led by Professor Michael ...

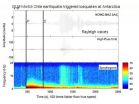

2010 Chilean earthquake causes icequakes in Antarctica

2014-08-10

VIDEO:

High-frequency icequakes are shown at station HOWD in Antarctica during the distant waves of the 2010 magnitude 8.8 Chile earthquake. The triggered icequakes are indicated by the narrow vertical bands...

Click here for more information.

Seismic events aren't rare occurrences on Antarctica, where sections of the frozen desert can experience hundreds of micro-earthquakes an hour due to ice deformation. Some scientists call them icequakes. But in March of 2010, the ice sheets ...

Target identified for rare inherited neurological disease in men

2014-08-10

Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified the mechanism by which a rare, inherited neurodegenerative disease causes often crippling muscle weakness in men, in addition to reduced fertility.

The study, published August 10 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, shows that a gene mutation long recognized as a key to the development of Kennedy's disease impairs the body's ability to degrade, remove and recycle clumps of "trash" proteins that may otherwise build up on neurons, progressively impairing their ability to control muscle ...

The grass really is greener on TV and computer screens, thanks to quantum dots

2014-08-10

SAN FRANCISCO, Aug. 10, 2014 — High-tech specks called quantum dots could bring brighter, more vibrant color to mass market TVs, tablets, phones and other displays. Today, a scientist will describe a new technology called 3M quantum dot enhancement film (QDEF) that efficiently makes liquid crystal display (LCD) screens more richly colored.

His talk will be one of nearly 12,000 presentations at the 248th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society, taking place here through Thursday.

"Green grass just pops ...

Pregnant women and fetuses exposed to antibacterial compounds face potential health risks

2014-08-10

SAN FRANCISCO, Aug. 10, 2014 — As the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mulls over whether to rein in the use of common antibacterial compounds that are causing growing concern among environmental health experts, scientists are reporting today that many pregnant women and their fetuses are being exposed to these substances. They will present their work at the 248th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society.

The meeting, which takes place here through Thursday, features nearly 12,000 presentations on a ...

Wine symposium explores everything you wanted to know about the mighty grape (video)

2014-08-10

San Francisco, Aug. 10, 2014 — Location. Location. Location. The popular real estate mantra also

turns out to be equally important for growing wine grapes in fields and storing bottles of the beverage at home or in restaurants, according to researchers.

Those are just two of the topics that will be covered in a symposium titled, "Advances in Wine Research," that will run today through Tuesday at the 248th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). The meeting features nearly 12,000 reports. A brand-new ACS video on the topics is available ...