(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Martin Blaser, M.D., and Laura Cox, Ph.D., discuss their work on early antibiotic exposure in mice.

Click here for more information.

NEW YORK, August 14, 2014 — A new study published today in Cell suggests that antibiotic exposure during a critical window of early development disrupts the bacterial landscape of the gut, home to trillions of diverse microbes, and permanently reprograms the body's metabolism, setting up a predisposition to obesity. Moreover, the study shows that it is altered gut bacteria, rather than the antibiotics, driving the metabolic effects.

The new study by NYU Langone Medical Center researchers reveals that mice given lifelong low doses of penicillin starting in the last week of pregnancy or during nursing were more susceptible to obesity and metabolic abnormalities than mice exposed to the antibiotic later in life.

Most intriguing, in a complementary group of experiments, mice given low doses of penicillin only during late pregnancy through nursing gained just as much weight as mice exposed to the antibiotic throughout their lives.

"We found that when you perturb gut microbes early in life among mice and then stop the antibiotics, the microbes normalize but the effects on host metabolism are permanent," says senior author Martin Blaser, MD, the Muriel G. and George W. Singer Professor of Translational Medicine, director of the NYU Human Microbiome Program, and professor of microbiology at NYU School of Medicine. "This supports the idea of a developmental window in which microbes participate. It's a novel concept, and we're providing direct evidence for it."

The researchers stress that more evidence is needed before it can be determined whether antibiotics lead to obesity in humans, and the present study should not deter doctors from prescribing antibiotics to children when they are necessary. "The antibiotic doses used in this study don't mirror what children get," says Laura M. Cox, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Blaser's laboratory and the lead author of the study. "But it has identified an early window in which microbes can influence metabolism, and so further studies are clearly warranted."

In one experiment in the study, Dr. Cox administered water with low doses of penicillin to three groups of mice. One group received antibiotics in the womb during the last week of pregnancy and continued the medication throughout life. The second group received the same dose of penicillin after weaning and, like the first group, continued it throughout life. The third received no antibiotics. "We saw increased fat mass in both penicillin groups, but it was higher in the mice who received penicillin starting in the womb," Dr. Cox says. "This showed that mice are more metabolically vulnerable if they get antibiotics earlier in life."

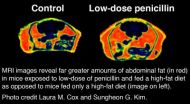

The treated mice also grew fatter than the untreated mice when both were fed a high-fat diet. "When we put mice on a high-calorie diet, they got fat. When we put mice on antibiotics, they got fat," explains Dr. Blaser. "But when we put them on both antibiotics and a high-fat diet, they got very, very fat." Normally, adult female mice carry three grams of fat. The animals in the study fed the high-fat diet had five grams of fat. By comparison, the mice who received antibiotics plus the high-fat chow packed on 10 grams of fat, accounting for a third of their body weight. The treated rodents were not only fatter but also suffered elevated levels of fasting insulin, and alterations in genes related to liver regeneration and detoxification—effects consistent with metabolic disorders in obese patients.

This work confirms and extends landmark research published by Dr. Blaser's lab in 2012 in Nature. That research showed that mice on a normal diet who were exposed to low doses of antibiotics throughout life, similar to what occurs in commercial livestock, packed on 10 to 15 percent more fat than untreated mice and had a markedly altered metabolism in their liver.

Among the unanswered questions in that study was whether the metabolic changes were the result of altered bacteria or antibiotic exposure. This latest study addresses the question by transferring bacterial populations from penicillin-exposed mice to specially bred germ-free, antibiotic-free mice, starting at three weeks of age, which corresponds to infancy just after weaning. The researchers discovered that mice inoculated with bacteria from the antibiotic-treated donors were indeed fatter than the germ-free mice inoculated with bacteria from untreated donors. "This shows us that the altered microbes are driving the obesity effects, not the antibiotics," says Dr. Cox.

Contrary to a longstanding hypothesis within the agricultural world that holds that antibiotics reduce total microbial numbers in the gut, therefore reducing competition for food and allowing the host organism to grow fatter, the team found that the penicillin did not, in fact, diminish bacterial abundance. It did, however, temporarily suppress four distinct organisms early in life during the critical window of microbial colonization: Lactobacillus, Allobaculum, Candidatus Arthromitus, and an unnamed member of the Rikenellaceae family, which may have important metabolic and immunological interactions. "We're excited about this because not only do we want to understand why obesity is occurring, but we also want to develop solutions," says Dr. Cox. "This gives us four potential new candidates that might be promising probiotic organisms. We might be able to give back these organisms after antibiotic treatments."

The researchers worked with six different mouse models over five years to obtain their results. To identify bacteria, they used a powerful molecular method that involves extracting DNA and sequencing a subunit of genetic material called 16S ribosomal DNA. Altogether, the scientists evaluated 1,007 intestinal samples, which yielded more than 6 million sequences of bacterial ribosomal genes, the order of the nucleotides that spell out DNA. Studies like these are possible because of technological advances in high-throughput sequencing, which allows scientists to survey microbes in the gut and other parts of the body. The Genome Technology Center at NYU Langone Medical Center played a key role in identifying the genetic sequences in the study.

INFORMATION:

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge assistance with sequencing from Argonne National Laboratory and NYULMC Genome Technology Center, and help from the NYULMC Histology Core, and the New York Genome Center.

These studies were supported by NIH grants R01 DK 090989 and 1UL1RR029893, the Diane Belfer Program in Human Microbial Ecology, Knapp Family Foundation, and Daniel Ziff Foundation.

About NYU Langone Medical Center

NYU Langone Medical Center, a world-class patient-centered, integrated academic medical center, is one of the nation's premier centers for excellence in clinical care, biomedical research, and medical education. Located in the heart of Manhattan, NYU Langone comprises three hospitals—Tisch Hospital, its flagship acute care facility; the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, the world's first university-affiliated facility devoted entirely to rehabilitation medicine; and the Hospital for Joint Diseases, one of only five hospitals in the nation dedicated to orthopaedics and rheumatology—plus NYU School of Medicine, which, since 1841, has trained thousands of physicians and scientists who have helped to shape the course of medical history. The medical center's trifold mission to serve, teach, and discover is achieved 365 days a year through the seamless integration of a culture devoted to excellence in patient care, education, and research. For more information, go to http://www.NYULMC.org.

Early antibiotic exposure leads to lifelong metabolic disturbances in mice

New study suggests bacteria help program metabolic development

2014-08-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Computation and collaboration lead to significant advance in malaria

2014-08-14

HOUSTON – (August 14, 2014) -- Researchers led by Baylor College of Medicine have developed a new computational method to study the function of disease-causing genes, starting with an important new discovery about a gene associated with malaria – one of the biggest global health burdens.

The work published today in the current issue of the journal Cell includes collaborators comprised of computational and evolutionary biologists and leading malaria experts from Baylor, Columbia University Medical Center, Princeton University, Pennsylvania State University and the National ...

Researchers identify a brain 'switchboard' important in attention and sleep

2014-08-14

VIDEO:

Michael Halassa, M.D., Ph.D. discusses his work with the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) and it's importance in identifying new targets for treating various psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia, autism and post-traumatic...

Click here for more information.

New York City, August 14, 2014 - Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center and elsewhere, using a mouse model, have recorded the activity of individual nerve cells in a small part of the brain that works as a "switchboard," ...

Genetic signal prevents immune cells from turning against the body

2014-08-14

LA JOLLA—When faced with pathogens, the immune system summons a swarm of cells made up of soldiers and peacekeepers. The peacekeeping cells tell the soldier cells to halt fighting when invaders are cleared. Without this cease-fire signal, the soldiers, known as killer T cells, continue their frenzied attack and turn on the body, causing inflammation and autoimmune disorders such as allergies, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered a key control mechanism on the peacekeeping cells that ...

Common mutation successfully targeted in Lou Gehrig's disease and frontotemporal dementia

2014-08-14

JUPITER, FL, August 14, 2014 – An international team led by scientists from the Florida campuses of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) and the Mayo Clinic have for the first time successfully designed a therapeutic strategy targeting a specific genetic mutation that causes a common form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), better known as Lou Gehrig's disease, as well a type of frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

The scientists developed small-molecule drug candidates and showed they interfere with the synthesis of an abnormal protein that plays a key role in causing ...

Scientists use lasers to control mouse brain switchboard

2014-08-14

VIDEO:

Scientists studied how just a few nerve cell in the mouse brain may control the switch between internal thoughts and external distractions. Using optogenetics, a technique that uses light-sensitive molecules...

Click here for more information.

Ever wonder why it's hard to focus after a bad night's sleep? Using mice and flashes of light, scientists show that just a few nerve cells in the brain may control the switch between internal thoughts and external distractions. The ...

Long antibiotic treatments: Slowly growing bacteria to blame

2014-08-14

Whether pneumonia or sepsis – infectious diseases are becoming increasingly difficult to treat. One reason for this is the growing antibiotic resistance. But even non-resistant bacteria can survive antibiotics for some time, and that's why treatments need to be continued for several days or weeks. Scientists at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel showed that bacteria with vastly different antibiotic sensitivity coexist within the same tissue. In the scientific journal Cell they report that, in particular, slowly growing pathogens hamper treatment.

Many bacteria ...

Tissue development 'roadmap' created to guide stem cell medicine

2014-08-14

In a boon to stem cell research and regenerative medicine, scientists at Boston Children's Hospital, the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and Boston University have created a computer algorithm called CellNet as a "roadmap" for cell and tissue engineering, to ensure that cells engineered in the lab have the same favorable properties as cells in our own bodies. CellNet and its application to stem cell engineering are described in two back-to-back papers in the August 14 issue of the journal Cell.

Scientists around the world are ...

Antibodies, together with viral 'inducers,' found to control HIV in mice

2014-08-14

Although HIV can now be effectively suppressed using anti-retroviral drugs, it still comes surging back the moment the flow of drugs is stopped. Latent reservoirs of HIV-infected cells, invisible to the body's immune system and unreachable by pharmaceuticals, ensure that the infection will rebound after therapy is terminated.

But a new strategy devised by researchers at Rockefeller University harnesses the power of broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV, along with a combination of compounds that induce viral transcription, in order to attack these latent reservoirs ...

Researchers identify a mechanism that stops progression of abnormal cells into cancer

2014-08-14

(Boston)-- Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) report that a tumor suppressor pathway, called the Hippo pathway, is responsible for sensing abnormal chromosome numbers in cells and triggering cell cycle arrest, thus preventing progression into cancer.

Although the link between abnormal cells and tumor suppressor pathways—like that mediated by the well known p53 gene—has been firmly established, the critical steps in between are not well understood. According to the authors, whose work appears in Cell, this work completes at least one of the ...

Researchers develop strategy to combat genetic ALS, FTD

2014-08-14

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — A team of researchers at Mayo Clinic and The Scripps Research Institute in Florida have developed a new therapeutic strategy to combat the most common genetic risk factor for the neurodegenerative disorders amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). In the Aug. 14 issue of Neuron, they also report discovery of a potential biomarker to track disease progression and the efficacy of therapies.

The scientists developed a small-molecule drug compound to prevent abnormal cellular processes caused by a ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

With the right prompts, AI chatbots analyze big data accurately

Leisure-time physical activity and cancer mortality among cancer survivors

Chronic kidney disease severity and risk of cognitive impairment

Research highlights from the first Multidisciplinary Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Symposium

New guidelines from NCCN detail fundamental differences in cancer in children compared to adults

Four NYU faculty win Sloan Foundation research fellowships

[Press-News.org] Early antibiotic exposure leads to lifelong metabolic disturbances in miceNew study suggests bacteria help program metabolic development