(Press-News.org) Using a deceptively simple set of experiments, researchers at Johns Hopkins have learned why people learn an identical or similar task faster the second, third and subsequent time around. The reason: They are aided not only by memories of how to perform the task, but also by memories of the errors made the first time.

"In learning a new motor task, there appear to be two processes happening at once," says Reza Shadmehr, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "One is the learning of the motor commands in the task, and the other is critiquing the learning, much the way a 'coach' behaves. Learning the next similar task goes faster, because the coach knows which errors are most worthy of attention. In effect, this second process leaves a memory of the errors that were experienced during the training, so the re-experience of those errors makes the learning go faster."

Shadmehr says scientists who study motor control — how the brain pilots body movement — have long known that as people perform a task, like opening a door, their brains note small differences between how they expected the door to move and how it actually moved, and they use this information to perform the task more smoothly next time. Those small differences are scientifically termed "prediction errors," and the process of learning from them is largely unconscious.

The surprise finding in the current study, described in Science Express on Aug. 14, is that not only do such errors train the brain to better perform a specific task, but they also teach it how to learn faster from errors, even when those errors are encountered in a completely different task. In this way, the brain can generalize from one task to another by keeping a memory of the errors.

To study errors and learning, Shadmehr's team put volunteers in front of a joystick that was under a screen. Volunteers couldn't see the joystick, but it was represented on the screen as a blue dot. A target was represented by a red dot, and as volunteers moved the joystick toward it, the blue dot could be programmed to move slightly off-kilter from where they pointed it, creating an error. Participants then adjusted their movement to compensate for the off-kilter movement and, after a few more trials, smoothly guided the joystick to its target.

In the study, the movement of the blue dot was rotated to the left or the right by larger or smaller amounts until it was a full 30 degrees off from the joystick's movement. The research team found that volunteers responded more quickly to smaller errors that pushed them consistently in one direction and less to larger errors and those that went in the opposite direction of other feedback. "They learned to give the frequent errors more weight as learning cues, while discounting those that seemed like flukes," says David Herzfeld, a graduate student in Shadmehr's laboratory who led the study.

The results also have given Shadmehr a new perspective on his after-work tennis hobby. "I'm much better in my second five minutes of playing tennis than in my first five minutes, and I always assumed that was because my muscles had warmed up," he says. "But now I wonder if warming up is really a chance for our brains to re-experience error."

"This study represents a significant step toward understanding how we learn a motor skill," says Daofen Chen, Ph.D., a program director at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. "The results may improve movement rehabilitation strategies for the many who have suffered strokes and other neuromotor injuries."

The next step in the research, Shadmehr says, will be to find out which part of the brain is responsible for the "coaching" job of assigning weight to different types of error.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper were Pavan A. Vaswani and Mollie K. Marko of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Memories of errors foster faster learning

2014-08-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Harnessing the power of bacteria's sophisticated immune system

2014-08-14

Bacteria's ability to destroy viruses has long puzzled scientists, but researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health say they now have a clear picture of the bacterial immune system and say its unique shape is likely why bacteria can so quickly recognize and destroy their assailants.

The researchers drew what they say is the first-ever picture of the molecular machinery, known as Cascade, which stands guard inside bacterial cells. To their surprise, they found it contains a two-strand, unencumbered structure that resembles a ladder, freeing it to ...

Message to parents: Babies don't 'start from scratch'

2014-08-14

There's now overwhelming evidence that a child's future health is influenced by more than just their parents' genetic material, and that children born of unhealthy parents will already be pre-programmed for greater risk of poor health, according to University of Adelaide researchers.

In a feature paper called "Parenting from before conception" published in today's issue of the top international journal Science, researchers at the University's Robinson Research Institute say environmental factors prior to conception have more influence on the child's future than previously ...

A self-organizing thousand-robot swarm

2014-08-14

Cambridge, Mass. – August 14, 2014 – The first thousand-robot flash mob has assembled at Harvard University.

"Form a sea star shape," directs a computer scientist, sending the command to 1,024 little bots simultaneously via an infrared light. The robots begin to blink at one another and then gradually arrange themselves into a five-pointed star. "Now form the letter K."

The 'K' stands for Kilobots, the name given to these extremely simple robots, each just a few centimeters across, standing on three pin-like legs. Instead of one highly-complex robot, a "kilo" of robots ...

Molecular engineers record an electron's quantum behavior

2014-08-14

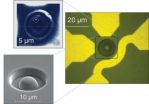

A team of researchers led by the University of Chicago has developed a technique to record the quantum mechanical behavior of an individual electron contained within a nanoscale defect in diamond. Their technique uses ultrafast pulses of laser light both to control the defect's entire quantum state and observe how that single electron state changes over time. The work appears in this week's online Science Express and will be published in print later this month in Science.

This research contributes to the emerging science of quantum information processing, which demands ...

Mysteries of space dust revealed

2014-08-14

The first analysis of space dust collected by a special collector onboard NASA's Stardust mission and sent back to Earth for study in 2006 suggests the tiny specks, which likely originated from beyond our solar system, are more complex in composition and structure than previously imagined.

The analysis, completed at a number of facilities including the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab) opens a door to studying the origins of the solar system and possibly the origin of life itself.

"Fundamentally, the solar system and everything ...

New Milky Way maps help solve stubborn interstellar material mystery

2014-08-14

An international team of sky scholars, including a key researcher from Johns Hopkins, has produced new maps of the material located between the stars in the Milky Way. The results should move astronomers closer to cracking a stardust puzzle that has vexed them for nearly a century.

The maps and an accompanying journal article appear in the Aug. 15 issue of the journal Science. The researchers say their work demonstrates a new way of uncovering the location and eventually the composition of the interstellar medium—the material found in the vast expanse between star systems ...

CF mucus defect present at birth

2014-08-14

VIDEO:

This is a 3-D reconstruction from time-lapse CT-scans of a CF pig lung. Images show the trachea and bronchi. Colored round dots represent positions of particles that were...

Click here for more information.

Mucus is key to keeping our lungs clean and clear of bacteria, viruses, and other foreign particles that can cause infection and inflammation. When we inhale microbes and dust, they are trapped in the mucus and then swept up and out of the lungs via a process called ...

Potential drug therapy for kidney stones identified in mouse study

2014-08-14

Anyone who has suffered from kidney stones is keenly aware of the lack of drugs to treat the condition, which often causes excruciating pain.

A new mouse study, however, suggests that a class of drugs approved to treat leukemia and epilepsy also may be effective against kidney stones, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

The drugs are histone deacetylase inhibitors, or HDAC inhibitors for short. The researchers found that two of them — Vorinostat and trichostatin A — lower levels of calcium and magnesium in the urine. Both calcium ...

Broader organ sharing won't harm liver transplant recipients

2014-08-14

New research shows that broader sharing of deceased donor livers will not significantly increase cold ischemia time (CIT)—the time the liver is in a cooled state outside the donor suggesting that this is not a barrier to broader sharing of organs. However, findings published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, do indicate that broader sharing of organs will significantly increase the percentage of donor organs that are transported by flying rather than driving. ...

Scientists study 'talking' turtles in Brazilian Amazon

2014-08-14

AUDIO:

These are vocalizations made between adults and hatchlings (individual sounds repeated for the listener's benefit).

Click here for more information.

Turtles are well known for their longevity and protective shells, but it turns out these reptiles use sound to stick together and care for young, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society and other organizations.

Scientists working in the Brazilian Amazon have found that Giant South American river turtles actually ...