Pygmy phenotype developed many times, adaptive to rainforest

2014-08-18

(Press-News.org) The small body size associated with the pygmy phenotype is probably a selective adaptation for rainforest hunter-gatherers, according to an international team of researchers, but all African pygmy phenotypes do not have the same genetic underpinning, suggesting a more recent adaptation than previously thought.

"I'm interested in how rainforest hunter-gatherers have adapted to their very challenging environments," said George H. Perry, assistant professor of anthropology and biology, Penn State. "Tropical rainforests are difficult for humans to live in. It is extremely hot and humid with limited food, especially when fruit is not in season."

A phenotype is the outward expression of genetic makeup and while two individuals with the same phenotype may look alike, their genes may differ substantially. The pygmy phenotype exists in many parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, the Philippines and potentially in South America. The phenotype is usually associated with rainforest hunter-gathers, groups of people who do not farm, but obtain resources by hunting large and small animals and gathering fruit, nuts, insects and other available resources.

Perry and colleagues looked at the genetics of the Batwa rainforest hunter-gatherers of Uganda and compared them to their farming neighbors, the Bakiga, with whom they traditionally traded forest products for grain, and sometimes intermarry. The researchers also looked at the Baka rainforest hunter-gatherers and their farming neighbors the Nzebi/Nzime in central Africa. They report their results online today (Aug. 18) in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science.

The average height for Batwa men is five foot and for women it is four foot eight inches. Their short stature is not caused by a single genetic mutation as occurs in many forms of dwarfism, but is the result of a variety of genetic changes throughout the genome that influence height.

The researchers investigated 16 different genetic locations that were associated with short stature when they looked at individuals who were an admixture of Batwa and Bakiga. Several of these regions contained genes known to be involved with growth in humans. They then studied these regions to look for indications that the changes were ones that persisted because they were adaptive.

Genetic mutations occur in populations all the time. If they have a negative impact on the individual, they tend to disappear from the population quickly. If they have no noticeable impact for the good or bad, they might disappear as well, although more slowly. Mutations which have positive influence on individuals, making them more fit for their environment, tend to spread through the population.

Short stature may be adaptive for rainforest individuals for a variety of reasons, according to Perry. Small bodies require less food, which is adaptive for a food-limited location like the rainforest. Small bodies also generate less heat, which, in the heat and humidity of the rainforest, is adaptive. It is also easier for small, agile individuals to move through dense undergrowth and to climb trees.

The results of the genetic comparison indicated that there was a statistical difference between the two groups indicative of multi gene adaptation.

However, when they looked at the Baka of West Africa, they did not find the same types of changes in the 16 genetic locations.

"What we think we see is that regions of the genome that are involved in the Batwa's Pygmy phenotype do not look the same in West Africa," said Perry. "If the Pygmy phenotype were really old, then we would have expected the locations to be similar."

The fact that they are not, suggests that both of these Pygmy phenotypes arose independently, separated geographically, with different underlying genetics, but with individuals who look similar. This leaves the door open for a much later development of the Pygmy phenotype adaptation.

INFORMATION:

Also working on this project were Luis B. Barreiro, Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre and University of Montreal; Matthieu Foll, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and Swish Institute of Bioinformatics; Jean-Christophe Grenier, Department of pathology, Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre, Canada; Etienne Patin and Lluis Quintana-Murci, Institut Pasteur and Centre National De La Recherche Scientifique, France; Yohan Nédélec and Alain Pacis, Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre and University of Montreal; Maxime Barakatt and Simon Gravel, McGill University; Xiang Zhou, University of Chicago; Sam Nsobya, Makerere University, Uganda; Laurent Excoffier, University of Bern and Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics; and Nathaniel J. Dominy, Dartmouth College.

The David and Lucille Packard Foundation, the Human Frontiers Science Program, Institut Pasteur, CNRS and Simone & Cino del Duca Foundation supported this work.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bionic liquids from lignin

2014-08-18

While the powerful solvents known as ionic liquids show great promise for liberating fermentable sugars from lignocellulose and improving the economics of advanced biofuels, an even more promising candidate is on the horizon – bionic liquids.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) have developed "bionic liquids" from lignin and hemicellulose, two by-products of biofuel production from biorefineries. JBEI is a multi-institutional partnership led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) that was established by the ...

Proteins critical to wound healing identified

2014-08-18

Mice missing two important proteins of the vascular system develop normally and appear healthy in adulthood, as long as they don't become injured. If they do, their wounds don't heal properly, a new study shows.

The research, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, may have implications for treating diseases involving abnormal blood vessel growth, such as the impaired wound healing often seen in diabetes and the loss of vision caused by macular degeneration.

The study appears Aug. 18 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) online ...

Climate change will threaten fish by drying out Southwest US streams, study predicts

2014-08-18

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Fish species native to a major Arizona watershed may lose access to important segments of their habitat by 2050 as surface water flow is reduced by the effects of climate warming, new research suggests.

Most of these fish species, found in the Verde River Basin, are already threatened or endangered. Their survival relies on easy access to various resources throughout the river and its tributary streams. The species include the speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus), roundtail chub (Gila robusta) and Sonora sucker (Catostomus insignis).

A key component ...

Trees and shrubs invading critical grasslands, diminish cattle production

2014-08-18

TEMPE, Ariz. – Half of the Earth's land mass is made up of rangelands, which include grasslands and savannas, yet they are being transformed at an alarming rate. Woody plants, such as trees and shrubs, are moving in and taking over, leading to a loss of critical habitat and causing a drastic change in the ability of ecosystems to produce food — specifically meat.

Researchers with Arizona State University's School of Life Sciences led an investigation that quantified this loss in both the United States and Argentina. The study's results are published in today's online ...

Researchers obtain key insights into how the internal body clock is tuned

2014-08-18

DALLAS – August 18, 2014 – Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have found a new way that internal body clocks are regulated by a type of molecule known as long non-coding RNA.

The internal body clocks, called circadian clocks, regulate the daily "rhythms" of many bodily functions, from waking and sleeping to body temperature and hunger. They are largely "tuned" to a 24-hour cycle that is influenced by external cues such as light and temperature.

"Although we know that long non-coding RNAs are abundant in many organisms, what they do in the body, and how they ...

UM research improves temperature modeling across mountainous landscapes

2014-08-18

MISSOULA – New research by University of Montana doctoral student Jared Oyler provides improved computer models for estimating temperature across mountainous landscapes.

The work was published Aug. 12 in the International Journal of Climatology in an article titled "Creating a topoclimatic daily air temperature dataset for the conterminous United States using homogenized station data and remotely sensed land skin temperature."

Collaborating with UM faculty co-authors Ashley Ballantyne, Kelsey Jencso, Michael Sweet and Steve Running, Oyler provided a new climate dataset ...

Passport study reveals vulnerability in photo-ID security checks

2014-08-18

Security systems based on photo identification could be significantly improved by selecting staff who have an aptitude for this very difficult visual task, a study of Australian passport officers suggests.

Previous research has shown that people find it challenging to match unfamiliar faces.

"Despite this, photo-ID is still widely used in security settings. Whenever we cross a border, apply for a passport or access secure premises, our appearance is checked against a photograph," says UNSW psychologist Dr David White.

To find out whether people who regularly carry out ...

New study reveals vulnerability in photo-ID security checks

2014-08-18

Passport issuing officers are no better at identifying if someone is holding a fake passport photo than the average person, new research has revealed.

A pioneering study of Australian passport office staff by a team of psychologists from Aberdeen, York and Sydney, revealed a 15% error rate in matching the person to the passport photo they were displaying.

In real life this degree of inaccuracy would correspond to the admittance of several thousand travellers bearing fake passports.

The findings are published today (Monday August 18) in the journal PLOS ONE.

They ...

Older coral species more hardy, UT Arlington biologists say

2014-08-18

New research indicates older species of coral have more of what it takes to survive a warming and increasingly polluted climate, according to biologists from the University of Texas at Arlington and the University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez.

The researchers examined 140 samples of 14 species of Caribbean corals for a study published by the open-access journal PLOS ONE on Aug. 18.

Jorge H. Pinzón C., a postdoctoral researcher in the UT Arlington Department of Biology, is lead author on the study. Co-authors are Laura Mydlarz, UT Arlington associate professor of biology, ...

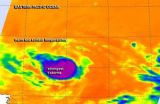

Tropical Storm Karina: status quo on infrared satellite imagery

2014-08-18

Since Tropical Storm Karina weakened from hurricane status, and since then, NASA satellite data has shown that the storm has been pretty consistent with strength and thunderstorm development.

Hurricane Karina formed on August 13, 2014 off the Mexican coast. The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite passed directly above the center of intensifying tropical storm Karina on August 14, 2014 at 1927 UTC (3:27 p.m. EDT). TRMM's Microwave Imager showed that storms near Karina's center were dropping rain at a rate of over 50mm (almost 2 inches) per hour. After ...