(Press-News.org) EVANSTON, Ill. -- A five-year old's brain is an energy monster. It uses twice as much glucose (the energy that fuels the brain) as that of a full-grown adult, a new study led by Northwestern University anthropologists has found.

The study helps to solve the long-standing mystery of why human children grow so slowly compared with our closest animal relatives.

It shows that energy funneled to the brain dominates the human body's metabolism early in life and is likely the reason why humans grow at a pace more typical of a reptile than a mammal during childhood.

Results of the study will be published the week of Aug. 25 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Our findings suggest that our bodies can't afford to grow faster during the toddler and childhood years because a huge quantity of resources is required to fuel the developing human brain," said Christopher Kuzawa, first author of the study and a professor of anthropology at Northwestern's Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. "As humans we have so much to learn, and that learning requires a complex and energy-hungry brain."

Kuzawa also is a faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern.

The study is the first to pool existing PET and MRI brain scan data -- which measure glucose uptake and brain volume, respectively -- to show that the ages when the brain gobbles the most resources are also the ages when body growth is slowest. At 4 years of age, when this "brain drain" is at its peak and body growth slows to its minimum, the brain burns through resources at a rate equivalent to 66 percent of what the entire body uses at rest.

The findings support a long-standing hypothesis in anthropology that children grow so slowly, and are dependent for so long, because the human body needs to shunt a huge fraction of its resources to the brain during childhood, leaving little to be devoted to body growth. It also helps explain some common observations that many parents may have.

"After a certain age it becomes difficult to guess a toddler or young child's age by their size," Kuzawa said. "Instead you have to listen to their speech and watch their behavior. Our study suggests that this is no accident. Body growth grinds nearly to a halt at the ages when brain development is happening at a lightning pace, because the brain is sapping up the available resources."

It was previously believed that the brain's resource burden on the body was largest at birth, when the size of the brain relative to the body is greatest. The researchers found instead that the brain maxes out its glucose use at age 5. At age 4 the brain consumes glucose at a rate comparable to 66 percent of the body's resting metabolic rate (or more than 40 percent of the body's total energy expenditure).

"The mid-childhood peak in brain costs has to do with the fact that synapses, connections in the brain, max out at this age, when we learn so many of the things we need to know to be successful humans," Kuzawa said.

"At its peak in childhood, the brain burns through two-thirds of the calories the entire body uses at rest, much more than other primate species," said William Leonard, co-author of the study. "To compensate for these heavy energy demands of our big brains, children grow more slowly and are less physically active during this age range. Our findings strongly suggest that humans evolved to grow slowly during this time in order to free up fuel for our expensive, busy childhood brains."

INFORMATION:

Leonard is professor and chair of the department of anthropology at Northwestern's Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

This study was a collaboration between researchers at Northwestern University, Wayne State University, Children's Hospital of Michigan, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, University of Illinois, George Washington University and Harvard Medical School.

The title of the paper, which is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is "Energetic costs and evolutionary implications of human brain development." Authors include Kuzawa and Leonard as well as Harry T. Chugani, Lawrence I. Grossman, Leonard Lipovich, Otto Muzik, Patrick R. Hof, Derek E. Wildman, Chet C. Sherwood and Nicholas Lange.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation's Biological Anthropology Program.

A long childhood feeds the hungry human brain

Study of brain scans explains why children grow slowly and childhood lasts so long

2014-08-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Black carbon -- a major climate pollutant -- also linked to cardiovascular health

2014-08-25

Black carbon pollutants from wood smoke are known to trap heat near the earth's surface and warm the climate. A new study led by McGill Professor Jill Baumgartner suggests that black carbon may also increase women's risk of cardiovascular disease.

To investigate the effects of black carbon pollutants on the health of women cooking with traditional wood stoves, Baumgartner, a researcher at McGill's Institute for the Health and Social Policy, measured the daily exposure to different types of air pollutants, including black carbon, in 280 women in China's rural Yunnan province.

Baumgartner ...

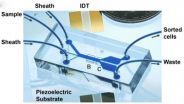

Tilted acoustic tweezers separate cells gently

2014-08-25

Precise, gentle and efficient cell separation from a device the size of a cell phone may be possible thanks to tilt-angle standing surface acoustic waves, according to a team of engineers.

"For biological testing we often need to do cell separation before analysis," said Tony Jun Huang, professor of engineering science and mechanics. "But if the separation process affects the integrity of the cells, damages them in any way, the diagnosis often won't work well."

Tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves can separate cells using very small amounts of energy. Unlike ...

New biomarker highly promising for predicting breast cancer outcomes

2014-08-25

A protein named p66ShcA shows promise as a biomarker to identify breast cancers with poor prognoses, according to research published ahead of print in the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology.

Cancer is deadly in large part due to its ability to metastasize, to travel from one organ or tissue type to another and malignantly sprout anew. The vast majority of cancer deaths are associated with metastasis.

In breast cancer, a process called "epithelial to mesenchymal transition" aids metastasis. Epithelial cells line surfaces which come into contact with the environment, ...

Exposure to toxins makes great granddaughters more susceptible to stress

2014-08-25

Scientists have known that toxic effects of substances known as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), found in both natural and human-made materials, can pass from one generation to the next, but new research shows that females with ancestral exposure to EDC may show especially adverse reactions to stress.

According to a new study by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and Washington State University, male and female rats are affected differently by ancestral exposure to a common fungicide, vinclozolin. Female rats whose great grandparents were exposed ...

MU researchers discover protein's ability to inhibit HIV release

2014-08-25

COLUMBIA, Mo. — A family of proteins that promotes virus entry into cells also has the ability to block the release of HIV and other viruses, University of Missouri researchers have found.

"This is a surprising finding that provides new insights into our understanding of not only HIV infection, but also that of Ebola and other viruses," said Shan-Lu Liu, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in the MU School of Medicine's Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology.

The study was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Liu, the ...

Cancer-fighting drugs might also stop malaria early

2014-08-25

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists searching for new drugs to fight malaria have identified a number of compounds -- some of which are currently in clinical trials to treat cancer -- that could add to the anti-malarial arsenal.

Duke University assistant professor Emily Derbyshire and colleagues identified more than 30 enzyme-blocking molecules, called protein kinase inhibitors, that curb malaria before symptoms start.

By focusing on treatments that act early, before a person is infected and feels sick, the researchers hope to give malaria –- especially drug-resistant strains ...

Sweet! Glycoconjugates are more than the sum of their sugars

2014-08-25

There's a certain type of biomolecule built like a nano-Christmas tree. Called a glycoconjugate, it's many branches are bedecked with sugary ornaments.

It's those ornaments that get all the glory. That's because, according to conventional wisdom, the glycoconjugate's lowly "tree" basically holds the sugars in place as they do the important work of reacting with other molecules.

Now a chemist at Michigan Technological University has discovered that the tree itself—called the scaffold—is a good deal more than a simple prop.

"We had always thought that all the biological ...

Doctors miss opportunities to offer flu shots

2014-08-25

Doctors should make a point of offering a flu vaccine to their patients. A simple reminder could considerably reduce the number of racial and ethnic minorities who currently do not vaccinate themselves against this common contagious respiratory illness. This recommendation is based on research led by Jürgen Maurer of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and the RAND Corporation in the US. Their findings¹ are published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Up to 50,000 Americans die annually of influenza and related diseases such as ...

New coping strategy for the memory impaired and their caregivers

2014-08-25

CHICAGO --- Mindfulness training for individuals with early-stage dementia and their caregivers together in the same class was beneficial for both groups, easing depression and improving sleep and quality of life, reports new Northwestern Medicine study.

"The disease is challenging for the affected person, family members and caregivers," said study lead author Ken Paller, professor of psychology at Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern and a fellow of the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center at Northwestern University Feinberg School of ...

To deter cyberattacks, build a public-private partnership

2014-08-25

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Cyberattacks loom as an increasingly dire threat to privacy, national security and the global economy, and the best way to blunt their impact may be a public-private partnership between government and business, researchers say. But the time to act is now, rather than in the wake of a crisis, says a University of Illinois expert in law and technology.

According to a study by Jay Kesan, the H. Ross and Helen Workman Research Scholar at the College of Law, an information-sharing framework is necessary to combat cybersecurity threats.

"Cybersecurity is ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] A long childhood feeds the hungry human brainStudy of brain scans explains why children grow slowly and childhood lasts so long