(Press-News.org) What's the price of your integrity? Tell the truth; everyone has a tipping point. We all want to be honest, but at some point, we'll lie if the benefit is great enough. Now, scientists have confirmed the area of the brain in which we make that decision.

The result was published online this week in Nature Neuroscience.

"We prefer to be honest, even if lying is beneficial," said Lusha Zhu, the study's lead author and a postdoctoral associate at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, where she works with Brooks King-Casas and Pearl Chiu, who are assistant professors at the institute and with Virginia Tech's Department of Psychology. "How does the brain make the choice to be honest, even when there is a significant cost to being honest?"

Previous studies have shown that brain areas behind the forehead, called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex, become more active during functional brain scanning when a participant is told to lie or to be honest.

But there's no way to know if those parts of the brain are engaged because an individual is lying or because he or she prefers to be honest, King-Casas said.

This time, researchers asked a different question.

"We asked whether there's a switch in the brain that controls the cost and benefit tradeoff between honesty and self-interest," Chiu said. "The answer to this question will help shed light on the nature of honesty and human preferences."

Researchers compared the decisions of healthy participants with decisions made by participants with damaged dorsolateral prefrontal cortices or orbitofrontal cortices.

The team, including scientists from the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and the University of California at Berkeley, had volunteers decide between honesty and self-interest in an economic "signaling game," which has been extensively studied in behavioral economics, game theory, and evolutionary biology.

In one game, the researchers presented participants with an option that gave them more money at a cost to an anonymous opponent, and an option that gave the opponent more money at a cost to the participant. Unsurprisingly, participants chose the option that filled their own pockets.

In a different game, the researchers presented participants with the same options and but asked the participants to send a message to their opponents, recommending one option over the other. The participants either lie and reap the reward, or tell the truth and suffer a loss.

"The average person usually shows lie aversion," Zhu said. "If they don't need to send a message, they prefer the option that gives them more money. If they do need to send a message, they're more likely to send a message that will benefit the other person even at a loss to themselves. They want to be honest, at the cost of their own wallet."

Participants with damage in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex were not as averse to lying as the two comparison groups. They were more likely to pick the practical option and were less concerned about the potential cost to self-image.

In the game where no message was required, however, participants with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex damage showed the same pattern of decision-making as the comparison groups, suggesting that for each group, the baseline tendency to give to others is the same.

"These results suggest that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain region known to be critically involved in cognitive control, may play a causal role in enabling honest behavior," Chiu said.

"People feel good when they're honest and they feel bad when they lie," King-Casas said. "Self-interest and self-image are both powerful factors influencing a person's decision to be honest."

Previous studies, according to King-Casas, were unable to control for an important distinction.

"In past studies, participants are typically instructed by the experimenter to lie or be honest. There's no consequence for lying; the subject is just complying," said King-Casas. "One of the real strengths of our study is that we're able to see how a person's tradeoffs change when we add in responsibility."

Another strength is the measurable tradeoff – when will an honest person decide the benefit is worth the lie?

"We manipulated the costs and benefits of honesty to quantify the tipping point for each person," said Chiu. "We picked tough dilemmas where, for example, telling a lie might harm the other player one cent, whereas being honest will cost you $20. And you might decide that being seen as an honest person is worth more than $20, so you won't lie even though it costs you, or you might decide that one cent of harm isn't so bad."

The study sheds light on the neuroscientific basis and broader nature of honesty. Moral philosophers and cognitive psychologists have had longstanding, contrasting hypotheses about the mechanisms governing the tradeoff between honesty and self-interest.

The "Grace" hypothesis, suggests that people are innately honest and have to control honest impulses if they want to profit. The "Will" hypothesis holds that self-interest is our automatic response.

"The prefrontal cortex is key to controlling our behavior and helps to override our natural impulses to be either honest or self-interested," King-Casas said. "Knowing this, we can test whether 'Grace' or 'Will' is dominant. By including participants with lesions in the prefrontal cortex, we were able to test whether honesty requires us to actively resist self-interest – in which case disrupting the prefrontal cortex would reduce the influence of honesty preferences – or whether we are automatically predisposed toward honesty, in which case disrupting the prefrontal cortex would instead enhance honest behavior. And our results show a necessary role for prefrontal control in generating honest behavior by overriding our tendencies to be self-interested.

"Our next step will be to combine functional brain imaging with economic modeling to understand how the brain computes the tradeoff between the costs and benefits of lying," King-Casas added. "Then we can begin to understand the nature of honesty."

INFORMATION:

Written by Ashley Wenners Herron.

Scientists find possible neurobiological basis for tradeoff between honesty, self-interest

Average person usually averse to lying, researchers say

2014-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers find Asian camel crickets now common in US homes

2014-09-02

With their long, spiky legs and their propensity for eating anything, including each other, camel crickets are the stuff of nightmares. And now research from North Carolina State University finds that non-native camel cricket species have spread into homes across the eastern United States.

"The good news is that camel crickets don't bite or pose any kind of threat to humans," says Dr. Mary Jane Epps, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State and lead author of a paper about the research.

The research stems from a chance encounter, when a cricket taxonomist found an invasive ...

Exceptionally well preserved insect fossils from the Rhône Valley

2014-09-02

In Bavaria, the Tithonian Konservat-Lagerstätte of lithographic limestone is well known as a result of numerous discoveries of emblematic fossils from that area (for example, Archaeopteryx). Now, for the first time, researchers have found fossil insects in the French equivalent of these outcrops - discoveries which include a new species representing the oldest known water treader.

Despite the abundance of fossils in the equivalent Bavarian outcrops, fewer fossils have been obtained from the Late Kimmeridgian equivalents of these rocks in the departments of Ain and Rhône ...

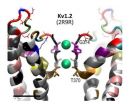

Surprising new role for calcium in sensing pain

2014-09-02

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you accidentally touch a hot oven, you rapidly pull your hand away. Although scientists know the basic neural circuits involved in sensing and responding to such painful stimuli, they are still sorting out the molecular players.

Duke researchers have made a surprising discovery about the role of a key molecule involved in pain in worms, and have built a structural model of the molecule. These discoveries, described Sept. 2 in Nature Communications, may help direct new strategies to treat pain in people.

In humans and other mammals, a family of ...

Single laser stops molecular tumbling motion instantly

2014-09-02

In the quantum world, making the simple atom behave is one thing, but making the more complex molecule behave is another story.

Now Northwestern University scientists have figured out an elegant way to stop a molecule from tumbling so that its potential for new applications can be harnessed: shine a single laser on a trapped molecule and it instantly cools to the temperature of outer space, stopping the rotation of the molecule.

"It's counterintuitive that the molecule gets colder, not hotter when we shine intense laser light on it," said Brian Odom, who led the research. ...

NYU study compares consequences of teen alcohol and marijuana use

2014-09-02

Growing public support for marijuana legalization in the U.S. has led to public debate about whether marijuana is "safer" than other substances, such as alcohol. In January, President Obama also publically stated he is not convinced that marijuana is more dangerous than alcohol. Despite the recent shift in views toward marijuana, the harms of use as compared to alcohol use are not well understood.

Now a new study "Adverse Psychosocial Outcomes Associated with Drug Use among US High School Seniors: A Comparison of Alcohol and Marijuana," by researchers affiliated with ...

Discovery hints at why stress is more devastating for some

2014-09-02

Some people take stress in stride; others are done in by it. New research at Rockefeller University has identified the molecular mechanisms of this so-called stress gap in mice with very similar genetic backgrounds — a finding that could lead researchers to better understand the development of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression.

"Like people, each animal has unique experiences as it goes through its life. And we suspect that these life experiences can alter the expression of genes, and as a result, affect an animal's susceptibility to stress," says senior ...

Simple awareness campaign in general practice identifies new cases of AF

2014-09-02

Barcelona, Spain – Tuesday 2 September 2014: A simple awareness campaign in general practice identifies new cases of atrial fibrillation (AF), according to research presented at ESC Congress today by Professor Jean-Marc Davy from France.

Professor Davy said: "Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. It multiplies the risk of heart failure risk by three-fold and the risk of stroke risk by five-fold. Similarly, AF is responsible for ischaemic stroke in 1 of 4 cases. However, AF is often overlooked and diagnosed too late. In 20% of cases, AF is diagnosed ...

ROCKET AF trial suggests that digoxin increases risk of death in AF patients

2014-09-02

Barcelona, Spain – Tuesday 2 September 2014: Digoxin may increase the risk of death in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) by approximately 20%, according to results from the ROCKET AF trial presented at ESC Congress today by Dr Manesh Patel, director of interventional cardiology and catheterisation labs at Duke University Health System in Durham, North Carolina, US. The findings suggest that caution may be needed when using digoxin in complex AF patients but further studies are needed to confirm the observations.

Dr Patel said: "In this subanalysis of the ROCKET AF ...

Health structures explain nearly 20 percent of non-adherence to heart failure guidelines

2014-09-02

Barcelona, Spain – Tuesday 2 September 2014: Health structures explain nearly 20% of the non-adherence to heart failure guidelines, according to the results of a joint ESC-OECD study presented today at ESC Congress by Professor Aldo Maggioni. Clinical variables explained more than 80% of non-adherence.

Professor Maggioni said: "This is a unique evaluation which combines clinical data and health structure characteristics of different countries. It provides a fuller picture of the reasons some patients with heart failure do not receive treatment according to ESC guidelines."

Heart ...

Mechanical heart valves increase pregnancy risk

2014-09-02

Barcelona, Spain – Tuesday 2 September 2014: The fact that mechanical heart valves increase risks during and after pregnancy, has been confirmed by data from the ROPAC registry presented for the first time today in an ESC Congress Hot Line session by Professor Jolien W. Roos-Hesselink, co-chair with Professor Roger Hall of the registry's executive committee. The registry found that 1.4% of pregnant women with a mechanical heart valve died and 20% lost their baby during pregnancy.

The Registry Of Pregnancy And Cardiac disease (ROPAC) is an ongoing worldwide registry that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

[Press-News.org] Scientists find possible neurobiological basis for tradeoff between honesty, self-interestAverage person usually averse to lying, researchers say