(Press-News.org) A brain region largely known for coordinating motor control has a largely overlooked role in childhood development that could reveal information crucial to understanding the onset of autism, according to Princeton University researchers.

The cerebellum — an area located in the lower rear of the brain — is known to process external and internal information such as sensory cues that influence the development of other brain regions, the researchers report in the journal Neuron. Based on a review of existing research, the researchers offer a new theory that an injury to the cerebellum during early life potentially disrupts this process and leads to what they call "developmental diaschisis," which is when a loss of function in one part of the brain leads to problems in another region.

The researchers specifically apply their theory to autism, though they note that it could help understand other childhood neurological conditions. Conditions within the autism spectrum present "longstanding puzzles" related to cognitive and behavioral disruptions that their ideas could help resolve, they wrote. Under their theory, cerebellar injury causes disruptions in how other areas of the brain develop an ability to interpret external stimuli and organize internal processes, explained first author Sam Wang, an associate professor of molecular biology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI).

"It is well known that the cerebellum is an information processor. Our neocortex [the largest part of the brain, responsible for much higher processing] does not receive information unfiltered. There are critical steps that have to happen between when external information is detected by our brain and when it reaches the neural cortex," said Wang, who worked with doctoral student Alexander Kloth and postdoctoral research associate Aleksandra Badura, both in PNI.

"At some point, you learn that smiling is nice because Mom smiles at you. We have all these associations we make in early life because we don't arrive knowing that a smile is nice," Wang said. "In autism, something in that process goes wrong and one thing could be that sensory information is not processed correctly in the cerebellum."

Mustafa Sahin, a neurologist at Boston's Children Hospital and associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, said that Wang and his co-authors build upon known links between cerebellar damage and autism to suggest that the cerebellum is essential to healthy neural development. Numerous studies — including from his own lab — support their theory, said Sahin, who is familiar with the work but was not involved in it.

"The association between cerebellar deficits and autism has been around for a while," Sahin said. "What Sam Wang and colleagues do in this perspective article is to synthesize these two themes and hypothesize that in a critical period of development, cerebellar dysfunction may disrupt the maturation of distant neocortical circuits, leading to cognitive and behavioral symptoms including autism."

Traditionally, the cerebellum has been studied in relation to motor movement and coordination in adults. Recent studies, however, strongly suggest that it also influences childhood cognition, Wang said. Several studies also have found a correlation between cerebellar injury and the development of a disorder in the autism spectrum, the researchers report. For instance, the researchers cite a 2007 paper in the journal Pediatrics that found that individuals who experienced cerebellum damage at birth were 40 times more likely to score highly on autism screening tests. They also reference studies in 2004 and 2005 that found that the cerebellum is the most frequently disrupted brain region in people with autism.

"What we realized from looking at the literature is that these two problems — autism and cerebellar injury — might be related to each other" via the cerebellum's influence on wider neural development, Wang said. "We hope to get people and scientists thinking differently about the cerebellum or about autism so that the whole field can move forward."

The researchers conclude by suggesting methods for testing their theory. First, by inactivating brain-cell electrical activity, it should be possible to pinpoint the developmental stage in which injury to one part of the brain affects the maturation of another. A second, more advanced method is to reconstruct the neural connections between the cerebellum and other brain regions; the federal BRAIN Initiative announced in 2013 aims to map the activity of all the brain's neurons. Finally, mouse brains can be used to disable and restore brain-region function to observe the "upstream" effect in other areas.

INFORMATION:

The paper, "The cerebellum, sensitive periods, and autism," was published Aug. 6 in Neuron. The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. R01 NS045193 and F31 MH098651), the Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation, and the Sutherland Cook Fund.

Early cerebellum injury hinders neural development, possible root of autism

2014-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Can data motivate hospital leaders to improve care transitions?

2014-09-02

What happens when you are hospitalized, but your outpatient doctor does not know? Or when you arrive at the office for follow-up care, but your doctor does not have the right information about your hospital stay? Missing or incomplete communication from hospitals to outpatient primary care physicians (PCPs) can contribute to poor experiences and lead to hospital readmissions.

However, a new study shows that implementing guidelines can improve hospitals' communication during patient care transitions. Researchers from Healthcentric Advisors collaborated with Rhode Island ...

Molecular probes permit doctors to detect diabetic retinopathy before vision fails

2014-09-02

A new study published in the September issue of The FASEB Journal, http://www.fasebj.org, identifies a novel strategy to diagnose the leading cause of blindness in adults, diabetic retinopathy, before irreversible structural damage has occurred. This advance involves quantifying the early molecular changes caused by diabetes on the endothelium of retinal vessels. Using new probes developed by scientists, they were able to distinguish the early molecular development of diabetic retinopathy.

"My goal is to establish a versatile clinical tool that alerts of a disease process ...

Research in rodents suggests potential for 'in body' muscle regeneration

2014-09-02

Winston-Salem, N.C. – Sept. 2, 2014 – What if repairing large segments of damaged muscle tissue was as simple as mobilizing the body's stem cells to the site of the injury? New research in mice and rats, conducted at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center's Institute for Regenerative Medicine, suggests that "in body" regeneration of muscle tissue might be possible by harnessing the body's natural healing powers.

Reporting online ahead of print in the journal Acta Biomaterialia, the research team demonstrated the ability to recruit stem cells that can form muscle tissue to ...

More than one-third of booked operations are re-booked

2014-09-02

More than one third of all planned orthopaedic surgery procedures are re-booked, postponed or cancelled completely. The most common reasons are cancellation at the patient's own request or emergency cases having to be prioritised. These are the findings of a study carried out by the Sahlgrenska Academy in association with Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

Postponed or cancelled operations are a problem both for the individual patient, who may have to wait longer for treatment, and for the hospital providing treatment in the form of poorer use of resources.

The Department ...

New synthesis method may shape future of nanostructures, clean energy

2014-09-02

COLLEGE PARK, Md. -- A team of University of Maryland physicists has published new nanoscience advances that they and other scientists say make possible new nanostructures and nanotechnologies with huge potential applications ranging from clean energy and quantum computing advances to new sensor development.

Published in the September 2, issue of Nature Communications the Maryland scientists' primary discovery is a fundamentally new synthesis strategy for hybrid nanostructures that uses a connector, or "intermedium," nanoparticle to join multiple different nanoparticles ...

University of Houston researcher looks at the future of higher education

2014-09-02

Most forecasts about the future of higher education have focused on how the institutions themselves will be affected – including the possibility of less demand for classes on campus and fewer tenured faculty members as people take courses online. Some changes already have begun.

When researchers at the University of Houston tackled the issue, they focused instead on what students will need in the future, including improved mentoring, personalized learning and feedback in real time.

The UH researchers identified three key themes:

A shift in the balance of power away ...

Family history of cardiovascular disease is not enough to motivate people to follow healthy lifestyle

2014-09-02

New research1 presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress in Barcelona shows that having a family history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is not enough to motivate people to follow healthy lifestyles.

Researchers used data from 188,139 users of HeartAge.me, a free online tool that engages people presenting their personal CVD risk factors as their estimated 'heart age', to test the hypothesis that those who have a family history of CVD are more likely to attend medical examinations and blood pressure checks and be motivated to adopt healthy diet and lifestyle ...

Researchers reveal carbon emissions of PlayStation®3 game distribution

2014-09-02

It's not always true that digital distribution of media will have lower carbon emissions than distribution by physical means, at least when file sizes are large.

That's the conclusion of a study published in Yale's Journal of Industrial Ecology that looked at the carbon footprint of games for consoles such as PlayStation®3. Researchers found that Blu-ray Discs delivered via retail stores caused lower greenhouse gas emissions than game files downloaded over broadband Internet. For their analysis, the investigators estimated total carbon equivalent emissions for an 8.8-gigabyte ...

Oceans apart: Study reveals insights into the evolution of languages

2014-09-02

A new Journal of Evolutionary Biology study provides evidence that physical barriers formed by oceans can influence language diversification.

Investigators argue that the same factor responsible for much of the biodiversity in the Galápagos Islands is also responsible for the linguistic diversity in the Japanese Islands: the natural oceanic barriers that impede interaction between speech communities. Therefore, spatially isolated languages gradually diverge from one another due to a reduction of linguistic contact.

"Charles Darwin would have been amused by a study like ...

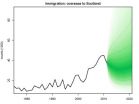

Coming or going? How Scottish independence could affect migration

2014-09-02

In light of the upcoming referendum on whether Scotland should be an independent country, researchers present a set of predictions of the possible effects on internal and international migration.

If Scotland declares independence, international immigration will remain the most uncertain flow. However, if large inflows occur, they are likely to be balanced by emigration from Scotland. Migration between Scotland and the rest of the UK is expected to remain at similar levels to the present, irrespective of the outcome of the 2014 independence referendum.

"International ...