(Press-News.org) Working with a team of scientists from the Technical University of Munich (TU Munich), Brandeis University, and Leiden University in the Netherlands, M. Cristina Marchetti and Mark Bowick, professors in the Soft Matter Program in the Syracuse University College of Arts and Sciences, have engineered and studied "active vesicles." These purely synthetic, molecularly thin sacs are capable of transforming energy, injected at the microscopic level, into organized, self-sustained motion.

Their findings are the subject of a cover-story in the Sept. 5 issue of Science magazine.

The ability to generate spontaneous motion and stable oscillations is a hallmark of living systems. Cells crawl to heal wounds, and the heart contracts periodically to pump blood through the entire body. Reproducing and understanding this behavior, both theoretically and experimentally, remains one of the great challenges of 21st-century science.

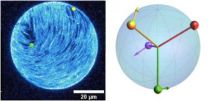

By confining cell extracts of important biological ingredients (i.e., bundles of long filamentary proteins known as microtubules and kinesin motor proteins) to the surface of a lipid vesicle, the TU Munich and Brandeis experimental part of the team has created "active vesicles" that undergo spontaneous oscillations and striking changes in shape. These biomimetic sacs are fueled by energy-consuming kinesins—nanomachines capable of transforming chemical energy into mechanical work--and may be thought of as the first step toward fabricating artificial cells.

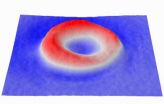

Fueled by kinesins, these defects form spatial patterns that oscillate between distinct configurations, turning the active vesicle into a robust miniature clock with tunable frequency.

When confined, the long microtubule bundles coat the surface of the vesicle, forming a liquid crystal, where the filaments are, on average, aligned in a common direction. This type of order, known as "nematic," is never perfect on a spherical surface (e.g., one cannot comb hair on a sphere without cowlicks). Hence, nematics on a sphere must contain a small number of defects.

Marchetti and Bowick have been working with Luca Giomi G'09, an alumnus of Syracuse's Soft Matter Program and an assistant professor at Leiden, in the development of a theoretical model that describes these defects as self-propelled particles on a thin liquid-crystalline shell and adequately explains the observed oscillations.

"Our work hinges on the wonderful experimental innovations of the [Andreas] Bausch and [Zvonimir] Dogic groups at TU Munich and Brandeis, respectively," says Marchetti, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Physics and associate director of the Syracuse Biomaterials Institute. "It has been gratifying to see that the theoretical work we have developed over the past 10 years, with some new ingredients, has been directly applicable to these experiments."

"I have worked on defects for over 20 years," adds Bowick, the J. Dorman Steele Professor of Physics and director of the soft matter program, "but I never imagined one could exploit them to create a tunable clock."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Bowick, Marchetti and Giomi, the Science article was co-written by Felix C. Keber and Etienne Loiseau, doctoral candidates in TU Munch's physics department; Tim Sanchez, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University (formerly at Brandeis); Stephen J. DeCamp, a graduate research assistant at Brandeis; Dogic, associate professor of physics at Brandeis; and Bausch, professor and chair of cellular biophysics at TU Munich.

Syracuse University physicists explore biomimetic clocks

Findings subject of a cover-story in the Sept. 5 issue of Science magazine

2014-09-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Thousands of nuclear loci via target enrichment and genome skimming

2014-09-05

The use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies in phylogenetic studies is in a state of continual development and improvement. Though the botanically-inclined have historically focused on markers from the chloroplast genome, the importance of incorporating nuclear data is becoming increasingly evident. Nuclear genes provide not only the potential to resolve relationships between closely related taxa, but also the means to disentangle hybridization and better understand incongruences caused by incomplete lineage sorting and introgression.

By harnessing the power ...

Social support: How to thrive through close relationships

2014-09-05

PITTSBURGH—Close and caring relationships are undeniably linked to health and well-being for all ages. Previous research has shown that individuals with supportive and rewarding relationships have better physical and mental health and lower mortality rates. However, exactly how meaningful relationships affect health has remained less clear.

In a new paper, Carnegie Mellon University's Brooke Feeney and University of California, Santa Barbara's Nancy L. Collins detail specific interpersonal processes that explain how close relationships help individuals thrive. Published ...

Dietary recommendations may be tied to increased greenhouse gas emissions

2014-09-05

ANN ARBOR—If Americans altered their menus to conform to federal dietary recommendations, emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases tied to agricultural production could increase significantly, according to a new study by University of Michigan researchers.

Martin Heller and Gregory Keoleian of U-M's Center for Sustainable Systems looked at the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of about 100 foods, as well as the potential effects of shifting Americans to a diet recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

They found that if Americans adopted ...

Disease in a dish approach could aid Huntington's disease discovery

2014-09-05

Creating induced pluripotent stem cells or iPS cells allows researchers to establish "disease in a dish" models of conditions ranging from Alzheimer's disease to diabetes. Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center have now applied the technology to a model of Huntington's disease (HD) in transgenic nonhuman primates, allowing them to conveniently assess the efficacy of potential therapies on neuronal cells in the laboratory.

The results were published in Stem Cell Reports.

"A highlight of our model is that our progenitor cells and neurons developed cellular ...

Novel immunotherapy vaccine decreases recurrence in HER2 positive breast cancer patients

2014-09-05

A new breast cancer vaccine candidate, (GP2), provides further evidence of the potential of immunotherapy in preventing disease recurrence. This is especially the case for high-risk patients when it is combined with a powerful immunotherapy drug. These findings are being presented by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology's Breast Cancer Symposium in San Francisco.

One of only a few vaccines of its kind in development, GP2 has been shown to be safe and effective for breast cancer patients, reducing recurrence ...

UT Southwestern researchers find new gene mutations for Wilms Tumor

2014-09-05

DALLAS – Sept. 5, 2014 – Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center and the Gill Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children's Medical Center, Dallas, have made significant progress in defining new genetic causes of Wilms tumor, a type of kidney cancer found only in children.

Wilms tumor is the most common childhood genitourinary tract cancer and the third most common solid tumor of childhood.

"While most children with Wilms tumor are thankfully cured, those with more aggressive tumors do poorly, and we are increasingly concerned about the long-term adverse ...

Study reveals breast surgery as a definitive and safe treatment for elderly patients

2014-09-05

Singapore, 5 September 2014 – A study conducted by National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) has shown that age per se is not a contraindication to breast cancer surgery, and such surgeries may be safely performed for women aged 80 years and above. Led by Dr Ong Kong Wee, Senior Consultant in the Division of Surgical Oncology, the team consists of Dr Veronique Tan, Consultant, and Dr Lee Chee Meng, Resident Doctor. The study explores the safety of breast cancer surgery in women aged 80 years and above.

A retrospective analysis was performed on 109 elderly women who underwent ...

Banked blood grows stiffer with age, study finds

2014-09-05

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — It may look like fresh blood and flow like fresh blood, but the longer blood is stored, the less it can carry oxygen into the tiny microcapillaries of the body, says a new study from University of Illinois researchers.

Using advanced optical techniques, the researchers measured the stiffness of the membrane surrounding red blood cells over time. They found that, even though the cells retain their shape and hemoglobin content, the membranes get stiffer, which steadily decreases the cells' functionality.

Led by electrical and computer engineering professor ...

Brain mechanism underlying the recognition of hand gestures develops even when blind

2014-09-05

Does a distinctive mechanism work in the brain of congenitally blind individuals when understanding and learning others' gestures? Or does the same mechanism as with sighted individuals work? Japanese researchers figured out that activated brain regions of congenitally blind individuals and activated brain regions of sighted individuals share common regions when recognizing human hand gestures. They indicated that a region of the neural network that recognizes others' hand gestures is formed in the same way even without visual information. The findings are discussed in ...

Synthetic messenger boosts immune system

2014-09-05

This news release is available in German. When a pathogen attacks a healthy cell in the body, T lymphocytes are tasked with identifying and destroying the infected cell. Scientists know that they undergo a "training program" for this task in the lymph nodes or the spleen. "Programming cells" play a key role here, presenting pathogen constituents to the T lymphocytes. This is how the T lymphocytes learn to recognize these components and become specialized "killer" cells. Research teams led by Prof. Percy Knolle from Klinikum rechts der Isar and the University of Bonn ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Syracuse University physicists explore biomimetic clocksFindings subject of a cover-story in the Sept. 5 issue of Science magazine